Home > Horse Care > Is your pasture good for your horse’s health?

Is your pasture good for your horse’s health?

- December 7, 2025

- ⎯ Christine Barakat

Using temporary fencing to restrict access to pasture space is a popular way to control the amount of calories horses take in while preserving the benefits of turnout. But a study from England suggests that the shape of a grazing space as well as its size can have a significant impact on a horse’s health and well-being.

“Strip” vs. “track” pasture management

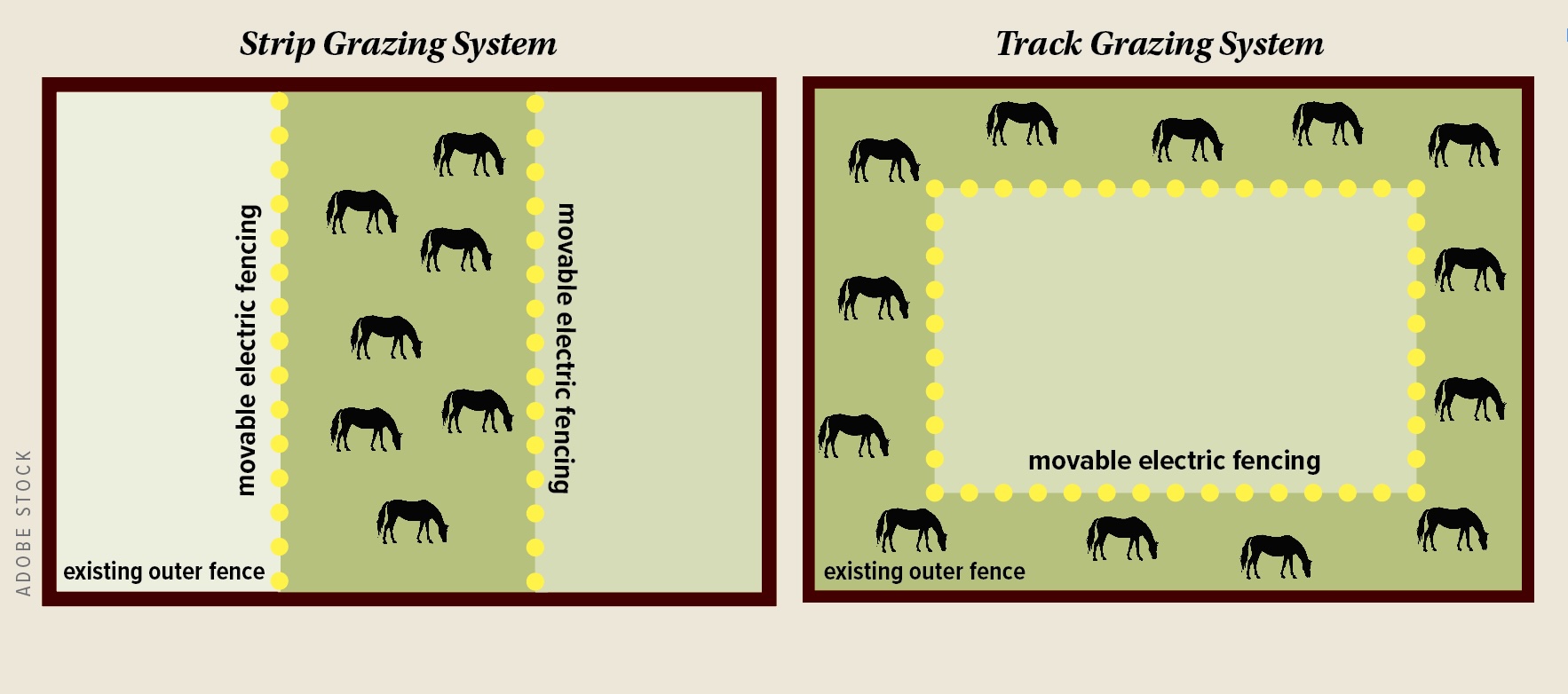

University of Lincoln researchers examined two commonly used methods of limiting pasture access. In the “strip” method, horses are confined to a small—typically rectangular—space. The “track” method involves the creation of a grazing track at the perimeter of the field. The grazing areas are established using temporary (often electric) fence panels that can be moved to adjust the shape and size of the space.

The experiment

For the experiment, the researchers selected 35 ponies from four well-established herds living on full turnout. For four weeks, each herd lived on a pasture within a strip-grazing enclosure or track-grazing enclosure. Each grazing configuration provided the same amount of grazable pasture. To avoid overgrazing, the researchers moved the electric fencing weekly on the track system and twice weekly on the strip system.

“Generally, most tracks are not moved regularly. But some people move sections of fencing to allow more access to grass in areas,” says Roxane Kirton, BVMS, MSc, MRCVS, who headed the study as part of her master’s work. “We moved the fencing in this study, so the field surface area remained the same between systems. Generally, however, once the grazing is insufficient in a track system, then supplementary forage would be provided.”

During the study periods, the researchers monitored the horses’ behavior using video, which was logged and categorized. The researchers paid particular attention to signs of positive welfare status, such as mutual grooming, and those that might suggest negative welfare status, such as combative interactions or cribbing.

What the data showed

The data showed that the horses in the track system moved more often and traveled greater distances. Kirton has a hypothesis on why that might be. “Having watched many hours of video footage, I think the horses tend to graze in a circular kind of pattern. This results in a much larger circumference on the track than on the strip, so they end up walking a lot farther. They also end up farther from stationary resources, such as the water trough, so may have to walk further to access these.”

In addition, the horses exhibited fewer combative interactions while in the track system. This may be a product of the resource placement, says Kirton. “I think it was likely because there was less concentration of resources [in particular areas] on the track. This meant less competition for resources, which is important in situations where food is restricted.”

The key to success

These results suggest physical as well as psychological health benefits to the track system as compared to the strip system or traditional paddocks. But Kirton emphasizes that a key to the success of any system is thoughtful implementation. “Track systems have the potential to be boring, barren environments that don’t adequately meet the needs of the horse, too,” she says. “A particular worry of mine is tracks that are too narrow. These may create situations where horses become trapped or don’t have sufficient space to get out of each other’s way. I do, however, believe that movement is really important for horse health and welfare. It worries me that many restrictive management practices don’t adequately provide for this especially when they are employed over longer periods of time.”

Reference: “The impact of restricted grazing systems on the behaviour and welfare of ponies,” Equine Veterinary Journal, September 2024