Home > Horse Care > Why Some Horses Have “Sticky” Stifles

Why Some Horses Have “Sticky” Stifles

- November 10, 2020

- ⎯ Editors of EQUUS

The equine stifle is equipped with a neat feature: The ability to “lock” in place to allow a horse to snooze while standing with minimal muscular exertion. That perk, however, comes with a potential downside. Sometimes the structure won’t unlock when needed, which prevents the horse from stepping forward.

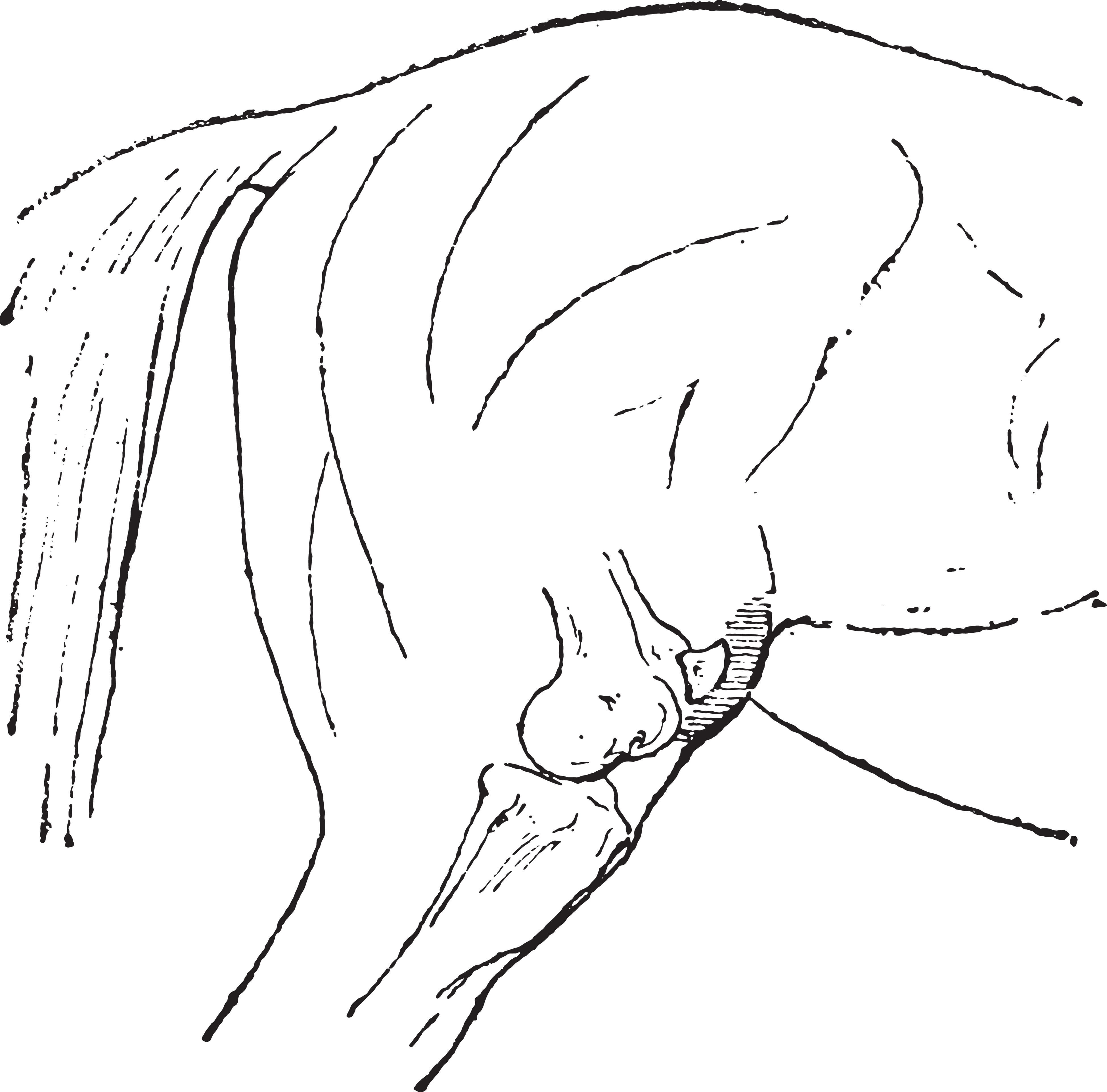

Stifles lock when the patella slides upward and the inner (medial) patellar ligament shifts slightly to hook over a notch in a knoblike end of the femur. Normally, a horse simply flexes the joint to release the lock—the ligament slides easily off its hook and the horse steps forward with no hesitation. In some horses, however, that release is delayed by a few seconds, leaving the leg extended as the horse attempts to move forward. This malfunction is known as upward fixation of the patella or “sticking stifles.”

What causes stifles to stick is not completely understood. One thought is that a lack of fitness in the thigh muscles may be the cause, but not all unfit horses have the problem. Conformation undoubtedly plays a role: Horses with upright stifles and hocks— those described as “post legged”—are much more likely to lock up.

Severe cases of sticking stifles are unmistakable: The horse attempts to walk forward but one hind leg remains extended and drags behind. Or the horse has to make a dramatic upward jerk of the limb every few strides to free the joint. There are other, more subtle signs, however. A horse may take shorter strides with a hind limb or drag his toes to prevent overflexion that can lead to locking. Or, he may have difficulty holding a canter lead or walking up or down hills. Any “oddness” in hind limb movement could be related to a sticky stifle and is worth investigating.

Conditioning is a first-line treatment for sticky stifles. When the muscles around the stifle joint are stronger, the patella is less likely to become stuck. Long, slow trots up hills that encourage the horse to lift and reach with his hind legs and flex through the stifle are the ideal type of exercise.

If conditioning isn’t helpful, other veterinary interventions can be tried, such as the use of injectable counterirritants to “thicken up” the ligament with scar tissue, making it less likely to stick. “Splitting” the ligament, by surgically creating many tiny stab incisions, has the same goal but with less risk of affecting other structures in the joint.

Cutting the medial patellar ligament, making it impossible for the patella to become stuck, was once a standard treatment for severe cases. The long-term consequences of the procedure, however, are a subject of debate, as is the proper post-surgical protocol.