Home > Horse Care > Snake Bite

Snake Bite

- April 28, 2022

- ⎯ Allison J. Stewart BVSc

Growing up in Australia, I was keenly aware of the threat that snakes posed. My native land is home to about 100 venomous species, and thousands of snakebites occur there every year—though fatalities are rare.

Here in the United States there are far fewer worrisome snakes, but that doesn’t mean that we equestrians need not be mindful of them. When reptiles and horses face off, the results can be ugly. Any bite is painful and frightening, and if the snake is poisonous, the subsequent swelling and tissue damage can be extreme and even life-threatening.

However, prompt action, followed by appropriate veterinary care, can mitigate the worst of the pain and health consequences associated with snakebites. Indeed, if you learn a few critical first-aid measures, you’ll be ready to reduce your horse’s risk of suffering the worst effects of a bite. Ultimately, you may never welcome the sight of one of these reptiles on your property or the trail. But, with good preparation, you’ll have no trouble keeping your cool if your paths should cross.

DIFFERENT KINDS OF BITES

In the United States, snakebite season coincides with warmer, longer days. In fact, nearly 90 percent of bites occur between April and October. Horses are sometimes bitten on the legs—typically after stepping on a snake—but more commonly they fall victim to their own curiosity, being struck on the nose as they naively confront a frightened reptile.

Fortunately, not all snakebites involve the injection of venom. So-called “dry” bites, from nonvenomous species or from poisonous snakes that withhold their venom, are essentially shallow puncture wounds. The fangs of most snakes are quite short, and the resulting wounds are smaller than the pricks from most thorny bushes. Infection is the main concern, but for multiple, deeper or more severe bites, a tetanus booster is advisable.

Of far greater consequence are bites involving the injection of venom, which is essentially saliva that contains toxins that can incapacitate prey. Depending on the snake species, venom may cause paralysis, respiratory distress, bleeding, prolonged bleeding or blood clotting and destruction of tissue. Dogs, cats, young foals and other small animals may die after a bite from a venomous snake, but the adult horse’s sheer size typically dilutes the toxins enough to make fatal systemic effects rare.

In mature horses, severe swelling is by far the most significant concern after snakebite, particularly if the bite is on the muzzle. If extreme swelling occurs, asphyxiation is a real threat because a horse can’t breathe through his mouth. Inflammation that starts on the exterior of the muzzle, at the site of a bite, can quickly worsen, compressing the nasal passages and cutting off the horse’s air supply.

Another major complication of snakebite is tissue destruction, which usually develops hours or days after the attack but can continue for weeks. As skin and muscle tissue around the site of the bite die, it sloughs away leaving large wounds that can become infected. Dead tissue also harbors bacteria, which can precipitate life-threatening gangrenous conditions.

BEFORE THE VETERINARIAN ARRIVES

If you know or suspect that your horse has been bitten by a snake, call your veterinarian immediately. Better to have a false alarm than to try to play catch-up later in a crisis situation. If you saw the strike and/or suspect the snake was venomous, your veterinarian may advise you to ship the horse immediately to a veterinary clinic. For a bite on the nose, however, he’ll likely instruct you to first assemble tools to keep the horse’s airway open in the event of extreme swelling. Virtually any sturdy, small tube will do, but I suggest cutting two six- to eight-inch-long segments from a garden hose or cut the ends off the barrel of a syringe. (If your trail rides take you through snake country, consider carrying these items at all times.)

If nasal swelling progresses rapidly or the horse’s breathing becomes noisy, wet one of the tubes with water or even spit and insert it carefully into the ventral (lower) portion of the nostril. Push it in about four inches—deep enough to stay put on its own. Nasal tubes inserted early can often allow sufficient air passage to negate the need to perform a tracheostomy.

Once you’ve ensured that the horse’s airway will stay open, take immediate action to minimize swelling and pain. Cold therapy will go a long way toward both goals. Apply ice—or the coldest water you have—directly to the bite site. If your horse was bitten on the leg, stand him in a bucket of ice water, or apply a large “stack wrap,” which extends from the coronet to the elbow or hock, and continually pour ice water over it.

As you tend to your horse, keep a close eye on any changes in his behavior or the appearance of the bite. If dramatic swelling suddenly appears or the horse begins to become overly excited or lethargic, it’s a good bet the snake was venomous. Call your veterinarian back with this information immediately.

TREATMENT GOALS

Your veterinarian may instruct you to transport the horse to a clinic, but many cases of snakebite can be medically managed on the farm. Either way, once it begins, veterinary treatment will be intensive and focused on the following goals:

*Preventing asphyxiation: If the horse is having trouble breathing, nasal tubes may be inserted, as previously described, or if the swelling is severe, a tracheostomy—the creation of an opening in the windpipe from underneath the throatlatch—maybe performed. Tracheostomies are a true emergency procedure: If a horse passes out and falls to the ground, it must be done within two to three minutes to prevent cardiac arrest and brain damage. Ideally, a tracheostomy is performed well before airflow is obstructed. Hospitalization of the horse is sometimes advised for around-the-clock airway monitoring.

- Controlling inflammation: Your veterinarian will likely give your horse anti-inflammatory drugs (Banamine or phenylbutazone) to control the inflammation and pain as long as the horse is adequately hydrated. Interestingly, anti-inflammatory drugs are not recommended for human snakebite victims because of the risk of exacerbating blood-clotting issues, but this does not appear to be a complication in equine victims.

- Preventing infection and disease: Like any puncture wound, a snakebite carries the risk of tetanus, so a vaccine booster may be administered. If the horse has not had a tetanus shot within the past 12 months, he will receive a booster. Generally, a veterinarian will also begin antibiotic therapy to combat infection from the bite itself as well as necrotic tissue that may develop in the aftermath.

- Countering the venom: In rare instances, a horse may receive snake antivenins, antibodies that bind to and neutralize venom in the bloodstream and tissues. Because of the expense, these products are generally reserved only for special equine cases—foals, for example, or horses who are already weakened by illness. For instance, it costs $400 to $600 for one vial of antivenin to treat a 40-pound dog.

The type of antivenin given depends on the type of snake that bit your horse. If you live in an area where there is only one type of venomous snake, then the diagnosis of which snake bit the animal will be easier to make. There are also multivalent antivenins, which are mixtures of antibodies against several snakes found in an area. In any case, the antivenin must be administered as soon as possible to bind to any circulating unbound venom. Many horses—even those bitten by highly venomous snakes—survive without antivenin.

Venomous Snakes of the United States

About 250 species and subspecies of snakes are found in the United States, but only four types are poisonous.

Copperheads

Subspecies: northern copperhead, southern copperhead, broad-banded copperhead, Osage copperhead, Trans-Pecos copperhead Location: the Florida panhandle north to Massachusetts and west to Nebraska. Copperheads live in rocky and wooded parts of hilly and mountainous areas. They are often found near woodpiles or sawdust. Appearance and behavior: Copperheads are named for their copper-colored heads; they have dark, chestnut colored, hourglass-shaped crossbands across the body. They are usually 24 to36 inches long. Younger copperheads are lighter in color and have a yellow tipped tail that they often flick. An agitated copperhead vibrates its tail rapidly.

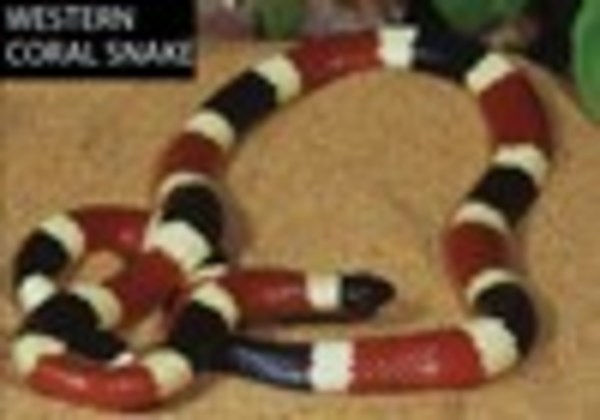

Coral snakes

Subspecies: Texas (Eastern) coral snake and Arizona (Western) coral snake Location: southern United States fromTexas to North Carolina, and southern Arizona to southwestern New Mexico. The nocturnal coral snake spends most of its life underground in cracks and crevices and is seldom seen. Appearance and behavior: Coral snakes have red and yellow bands located next to one another with a body framed in black, hence the old saying, “Red to yellow, kill a fellow.” Coral snakes usually grow to about 20 inches in length. When agitated, the coral snake often lays its head out of sight and rattles its tail, while emitting a popping sound.

Water moccasins (Cottonmouths)

Subspecies: Florida cottonmouth, western cottonmouth and eastern cottonmouth Location: throughout most of the Coastal Plains, ranging as far north asVirginia. Water moccasins, as the name implies, live in and around water. Appearance and behavior: Water moccasins are characterized by a brown, olive or blackish dark body and body crossbands that have a distinct border extending all the way around and across the yellowish stomach. They can grow up to 36 inches in length and have a triangular-shaped head and vertical pupils. Young moccasins have bright yellow or lime greenish tail tips. These snakes may vibrate their tails when agitated and can make a rattling sound when placed against leaves, water or solid objects. Cottonmouths are territorial and will guard and defend a specific area, which makes them seem more aggressive than other snakes.

Rattlesnakes

Subspecies: western diamondback rattlesnake, sidewinder or “horned rattlesnake” (known for sidewinding withits body in an S-shaped curve), black-tailed rattler, rock rattler, Mojave rattlesnake, Sonoran rattlesnake Location: most prevalent in the Southwestern United States, but also found in the North, East or South in diminishing numbers. Rattlesnakes live in desert flats, rocky hillsides, river bottoms, forested areas, grassy plains and prairies. Appearance and behavior: A rattlesnake is known for its triangular head, cat-like pupils and “rattle” on the end of his tail. The average length of an adult rattlesnake is three to four feet. When agitated, the snake will make a loud buzzing rattler sound along with a threatening coil.—Amanda Donohue

FOLLOW-UP CARE

The long-term veterinary care a horse requires depends on the location of the bite. It may take several days, for instance, for the swelling and pain to resolve enough for a horse bitten on the muzzle to be able to eat and drink. An adult horse can survive for a few days without food, but he must have water.

Dehydration is a particular concern if the horse is on anti-inflammatory drugs such as phenylbutazone and Banamine or certain antibiotics. These drugs can cause kidney damage if given to a horse who is low on fluids. If she has the opportunity before the muzzle swells, a veterinarian may insert a soft, narrow stomach tube through the nostril to deliver water and nourishment to a horse. If that’s not feasible, the horse may be started on intravenous fluids.

Your veterinarian will also want to monitor your horse’s vital signs for days after the bite to ensure there are no cardiac or neurological complications. She will also do repeated blood tests to detect potentially serious clotting problems. At the same time, she’ll monitor the skin around the bite for signs of tissue destruction. If the skin does die and slough off, it will be treated as any widespread tissue infection would be. This will likely require surgically removing dead skin, antibiotic therapy—both systemic and local—as well as bandaging and dressing the wound as appropriate to encourage regrowth of skin. In the worst cases, skin grafts may be necessary.

All of this requires intensive around-the-clock care that I think is best administered by a veterinary clinic. Costs vary by location and region, but our hospital charges between $30 and $150 a day to care for snake-bitten horses, which is likely to be far cheaper than repeated farm calls and much safer for the horse, ultimately.

FROM THE FIELD

True Grit To save his horse’s life after a snakebite, a cowboy is forced to take matters into his own hands.

A tracheostomy is best performed by a veterinarian, but I once talked a very brave owner through the procedure over a cell phone. The case involved a ranch horse that had been bitten on the nose by a venomous snake, and the owner was an older cowboy. As I drove to the ranch I kept in contact via cell phone.

The owner told me the horse’s nose and nasal passages were rapidly swelling and then, when I was still 10 minutes away, the horse suddenly collapsed.

I knew I couldn’t make it to the ranch in time to save the horse’s life so we had only one option. I pulled my truck off the road and told the owner I would guide him through an emergency tracheostomy procedure. Then I calmly began my instruction: I told him to use his pocketknife to make a three-inch vertical incision through the skin on the midline over the trachea (windpipe). Next, I said, make another one-inch horizontal incision through the thin muscle between two of the tracheal rings, no more than one third the diameter of the trachea. Finally, I guided him in inserting a four-inch length of garden hose through the incision and into the trachea, allowing the horse to breathe. As we finished this last step, I lost our phone connection.

I continued to the ranch, not knowing whether the procedure had been successful. To my relief, I found the horse standing calmly and breathing smoothly through the tracheostomy tube. But I was surprised to discover the owner passed out cold on the ground nearby.

Apparently the tough old cowboy had managed to finish the lifesaving procedure before the blood and pressure of the situation became too much for him. After confirming that the old fellow had merely fainted, I turned my attention to his horse, replacing the garden hose with a more secure metal tracheostomy tube and starting anti-inflammatory medications. The nose of the poor horse was swollen to double its normal size, and he was unable to close his lips. At the middle of his muzzle were the telltale pair of puncture wounds left behind by the snake’s strike. As I worked on the horse, the cowboy came to. He was glad to see me and said he could only barely remember performing the tracheostomy.

It took three days for the horse’s swelling to subside, and after a fourth we were able to remove the tracheostomy tube. The horse made a full recovery, but the cowboy informed me that he had decided not to pursue a career as an emergency surgeon.

Snakes have had a bad reputation since ancient times, but as a whole, they do far more good than harm. Nonvenomous snakes such as rat snakes, corn snakes or king snakes do us a great service by controlling populations of rodents in our barns and fields without posing any serious risk to anyone. Even the vast majority of venomous snakes tend to avoid both humans and horses and strike only when they feel cornered and threatened. In other words, you need not kill every snake you see on your farm—leave them alone and they’ll generally return the favor.

That said, if your horse is one of the unfortunate few to be bitten by a venomous snake, there’s no need to panic. Chances are he’ll be fine, and keeping your cool while taking immediate action will improve his odds of a swift and uneventful recovery even more.

FROM THE FIELD

A mare’s recovery from a snakebite on her face is complicated by a condition related to her plumpness.

Sometimes the personality that endears a horse to people eventually gets her in trouble. That’s what happened with Duchess, a 4-year-old pony who innocently nosed up to a snake and got bitten.

It happened in October, toward the end of a beautiful sunny day in Mobile, Alabama. At 8 p.m. we received an urgent call from Mary Penny, who was on her way to the Auburn University Large Animal Teaching Hospital with her pony, who had developed severe swelling over the right side of her face. Duchess had been completely normal when she was fed at 6 p.m. Because swelling was obviously progressing rapidly, Penny opted to take Duchess directly to Auburn.

The mare was admitted by our emergency service at 1 a.m. The clinicians examined her and found all her vital parameters normal, but the right side of her face was so swollen that her lips were pushed open and she was unable to open her right eye. The veterinarian inserted a nasotracheal tube into her right nostril to provide an airway.

Duchess’ bloodwork was normal, but because snake envenomation is associated with severe infections, a jugular catheter was inserted on her left side to deliver intravenous antibiotic, anti-inflammatory and analgesic medicationsas well as fluid therapy.

The little mare looked pathetic, and she was too uncomfortable to eat or drink. That night, and for the next few days, a dedicated team of senior veterinary students sat with Duchess and kept cold packs on her face for 10 minutes out of every two hours.

The next morning Duchess was transferred to the care of Rebecca Funk, DVM, MS, and me. Despite the anti-inflammatory drugs and cold-packing, the swelling of the pony’s face and neck had continued to worsen. It is not unusual for swelling due to snake envenomation to progress for 48 to 72 hours. Now our worry was a condition called hyperlipemia.

Most full-sized adult horses can go without feed for several days, but Miniature Horses, ponies and donkeys are prone to developing hyperlipemia if they do not eat for 24 to 48 hours. It occurs when fat stores are rapidly metabolized to supply the body with energy usually in response to the absence of eating.

The problem is that in overweight ponies, the rate of lipid (fat) breakdown overwhelms the liver’s metabolic processes. As a result, lipid becomes concentrated in the blood in the form of triglycerides and is deposited in organs such as the liver and kidneys, interfering with their function. Hyperlipemia can ultimately result in organ failure or rupture and death due to internal hemorrhage. To make matters worse, hyperlipemia causes the animal to feel ill and depressed, resulting in further disinterest in eating. Hyperlipemia is a vicious cycle—the worse the animal feels, the less food it consumes, and the faster the rate of fat breakdown.

Fortunately, Funk and I were familiar with treatment of snakebites and the prevention of hyperlipemia. We monitored Duchess’ serum triglyceride concentrations daily, and at the first sign of an increase we started a continuous rate infusion of dextrose and insulin. Her blood glucose concentrations were monitored every four hours, and we adjusted the flow rates of the dextrose and insulin as needed. It can take some time to individualize the rates for each patient, and Funk, being the resident on the case, had the task of making these adjustments all through the night. She set up a bed in the ICU office so she could be immediately informed of the glucose results by the evening ICU technician.

Intravenous dextrose can provide only a small portion of the total nutritional requirements. If Duchess would not eat the next day, we would have to add soluble proteins to her intravenous nutrition plan. This is relatively more expensive than dextrose alone.

Fortunately, by the next morning Duchess’ triglyceride and glucose concentrations were stable, and she appeared brighter. By afternoon she was even willing to eat small amounts of bran mash with sweet feed. Normally a greedy pony, Duchess would eat only if hand-fed by a veterinary student.

As the swelling began to dissipate and the mare’s appetite gradually returned, the intravenous drip and nasotracheal tube were removed and the pony was cleared for hand-grazing on the lawn outside the clinic. This cheered her up. Her serum was periodically tested for elevations in cardiac enzymes at the local human hospital, and we ran a 24-hour ECG test to ensure there were no irregularities in heart rhythm and electrical complexes. Everything seemed fine, and a week later Duchess was discharged with instructions to continue oral antibiotics and decreasing doses of Banamine.

When she returned to the university two months later for a follow-up and cardiac evaluation, she was her normal, healthy, curious self.

FROM THE FIELD

Prompt treatment and intensive nursing help a gelding recover after he is bitten by a venomous snake while walking along a river trail.

Linda Clayton didn’t see the attack on her 8-year-old Missouri Fox Trotter gelding, Ginger TJ, but the hallmarks of snakebite quickly became unmistakable.

It happened on the first of May, during a group trail ride along the banks of the Tombigbee River in Demopolis, Alabama. A few hours into the outing, two of the horses suddenly became startled for no obvious reason and five minutes later TJ suddenly started to stumble. Clayton dismounted and discovered blood dripping from her horse’s right foreleg and hind leg.

As luck would have it, a veterinarian, Stephanie Ostrowski, DVM, MPVM, DACVPM, was part of the trail ride group. At first, she thought the gelding might have become entangled in some thorny vines, but as she looked more carefully, she noticed the double spots of blood about an inch apart over the front of his right cannon below the knee and on the outside of his right hock. They looked, she thought, remarkably like snakebites.Water moccasins and rattlesnakes are found in the local area, especially along the river.

Over the next five minutes, TJ’s condition deteriorated. His breathing became labored and noisy, and then he started staggering. Finally, he collapsed on the side of the trail. Ostrowski and Clayton quickly removed his saddle. His mucous membranes (gums) were a horrible grayish purple and his ears were as cold as ice. Ostrowski really didn’t think TJ was going to make it, but she instructed her husband to ride back to the barn and collect her emergency vet box from the trailer.

A specialist in toxicology, Ostrowski suspected the rapidly progressing shock was caused by a neurotoxin. It seemed like an eternity before her husband returned, and without her drugbox she felt completely helpless. All she could do was try to calm both TJ and her friend Clayton.

Luckily, TJ was still a live by the time her husband returned on a four wheeler. Ostrowski administered drugs to treat the shock as well as anti-inflammatory and painkilling medications. The gelding responded fairly quickly, and after several minutes he was strong enough to rise to his feet. Clayton led TJ, as calmly as she could, along the trail to the nearest vehicle access point, where a trailer was on the way to pick him up.

Back at the farm, Ostrowski called Clayton’s regular veterinarian, Robby Crum, DVM to let him know what had happened. Crum is usually able to treat most cases of snakebite himself, but based on the severity of TJ’s neurotoxic signs he and Ostrowski decided it was best to transport the gelding to the intensive care unit of the Auburn University Teaching Hospital.

Although TJ’s systemic condition had improved markedly, both of the affected legs were beginning to swell. With TJ already loaded up, Clayton immediately set out on the three-hour trip to Auburn.

While TJ was en route, I received a call from Crum, who filled me in on the details of the case as best he could. My resident, Tricia Salazar, MS, DVM, DACVIM, and I were waiting when the trailer pulled in at around 11:30 p.m., but even with the information we’d been provided, we were surprised at the severity of the swelling and bruising on TJ’s right legs. There was gross swelling from the coronary bands to his elbow in front, and up to the gaskin behind. Bloody fluid was oozing through the skin over his front cannon, rear fetlock and hock. The surrounding skin was an angry dark purple.

We realized it was possible that all this damaged skin could eventually slough off and, worse case, might require skin grafts to heal.

Although we could not be 100 percent sure, the original reports of fang marks, rapid swelling and the location of the bites pointed to attacks from a water moccasin or rattlesnake. Water moccasins can be quite aggressive and may have spooked the first two horses, then bitten TJ. Rattlesnake bites are often more severe, with a mix of toxins that can damage cells and the nervous system. Poor TJ had probably stepped on the creature and been bitten at least three times.

The venom released by the snake was certainly having systemic effects as well. TJ’s respiratory rate was elevated at 48 breaths per minute (normal is from 10 to 24 breaths per minute). His heart rate was elevated at 66 beats per minute (compared to the normal range of 28 to 44 per minute), but his electrocardiogram (ECG) was normal. His mucous membranes were dark pink and tacky to the touch—a sign of systemic shock and stress—and he had a mild fever, with a rectal temperature of 101.9 degrees Fahrenheit (normal is 99.5 to 101.5 degrees).

Salazar went to work immediately, inserting a jugular vein catheter and starting intravenous fluid therapy. She also gave TJ more analgesics and a light sedative to allow us to clip the coat over his wounds. Even with the skin shaved clean, the original puncture wounds could not be seen because of the swelling. We cold-hosed his legs and then applied stack wraps from the coronary bands to the elbow/gaskin. Because his left legs were bearing more weight, we applied support wraps to them.

As we attended to his legs, we started TJ on intravenous antibiotics to combat the bacteria commonly found in the mouths of reptiles. The tissue destruction secondary to venom injection provides an ideal environment for bacterial proliferation, so we needed to get ahead of any infection.

The laboratory analyzed TJ’s bloodwork, and a urine sample showed that he was dehydrated and had an elevated white blood cell count. His kidney function was normal, however, allowing us to safely administer phenylbutazone for his pain. TJ was almost due for his vaccines, so we also administered a tetanus toxoid. All of this took place within two hours of his arrival at the clinic.

Overnight, TJ’s vital parameters, red cell count and plasma protein concentration were monitored every four hours. His red cell count remained stable, but his protein concentration began to fall. In addition, fluid began to collect under the skin between his front legs and back to the girth area. These clues told us the vessels in his bitten legs were seeping large amounts of protein-rich fluid.

Although the bandages had prevented further swelling in the right limbs, the fluid had been forced over the top of the bandages and was now accumulating under the chest and belly. Seepage from the skin of both legs continued and the skin was warm and very firm.

Because TJ was taking the majority of his weight on his two left legs, there was some concern about the development of “supporting limb” laminitis in his left hooves. We also worried about his right hooves due to the swelling and vessel damage. Because it’s better to prevent laminitis than try to treat it, we decided to place cushion supports under each of his feet. Luckily, he never developed laminitis.

Later that day, TJ’s blood protein concentration plummeted, a result of the leakiness of his vessels. This was worrisome because in order to keep fluid within the vascular space, blood protein must be high enough to balance the pressures that draw fluid out of the vessels. When a horse’s blood serum protein level falls below 4 mg/dL, he is at risk of serious whole body edema formation, a potentially grave complication. TJ’s protein had fallen to 3.8 mg/dL.

TJ needed a transfusion of four liters of plasma, along with a synthetic colloid product called hetastarch. Composed of some large molecules, hetastarch is believed to block some of the holes in the leaky blood vessels and provide oncotic forces to draw fluid back from the tissue into the blood vessels. The cost of the plasma and hetastarch was more than $1,000. Clayton, however, decided it was worth the investment to give her horse the best chance of survival.

By the next day, TJ was much more comfortable. His plasma protein concentration had stabilized and the edema was no longer progressing. His bloodwork was almost normal and his appetite had returned. We exchanged the stack wraps, which we were redoing twice a day, for German-made equine compression stockings imported by our intern Malte Harland, DVM.

Harland had studied the flow of lymph in lymphatic vessels under bandages for his thesis and found more uniform tissue compression and superior lymphatic flow with the stockings, which conformed to the legs more evenly than bandages can.

Over the next six days TJ continued to improve, and his owner visited regularly. There was a significant decrease in the swelling and edema in his legs. The majority of the skin over his limbs was healthy and intact, apart from a small section over the right front limb, similar to what would be seen with sunburn. We were periodically monitoring his heart rhythm and cardiac enzymes, and both appeared normal.

A week after he arrived at Auburn, TJ was sent home, still on oral antibiotics and phenylbutazone, and with twice daily hydrotherapy and leg bandaging. Crum would visit him at home periodically for the next several months to monitor his bloodwork, cardiac enzymes and heart rhythm.

In the end, Ginger TJ made an uneventful recovery and in the six years since his run-in with a snake has enjoyed many more trail rides with Clayton. I do wonder if he keeps a closer eye out for what’s underfoot, though.