When EHV-1 turns deadly

- October 7, 2020

- ⎯ Heather Smith Thomas

In this age of pandemic, everyone has become familiar with, if not expert in, measures that control the spread of disease: Social distancing. Disinfection. Quarantine. These fundamentals of biosecurity might once have been abstractions but now have taken on practical importance in our lives.

Of course, the horse world has long made the control of certain diseases a priority. And thanks to another pillar of disease prevention—vaccination—we’ve largely been successful in protecting horses from rabies, equine encephalomyelitis, West Nile virus and other infectious scourges.

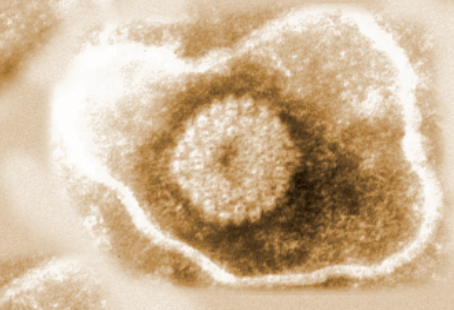

Yet some pathogens continue to pose a threat despite even the most stringent hygiene measures and vaccination programs. Equine herpesvirus-1 (EHV-1) is one such organism. Even without physical contact, this highly contagious respiratory virus can spread rapidly from horse to horse through nasal discharge or aerosol droplets.

Although most cases cause mild-to-moderate respiratory illness (rhinopneumonitis), EHV-1 infection occasionally leads to a life-threatening neurologic disease known as equine herpesvirus myeloencephalopathy (EHM). The mechanisms through which EHV-1, and even more rarely EHV-4, produce neurologic disease are not yet understood. So your best bet is to reduce your horse’s exposure to pathogens in general.

You might think this year’s disrupted horse-show season and event schedules, along with depopulated equestrian venues, would have eliminated the threat of EHM, but that’s not the case. A quick scan of the Equine Disease Communication Center database shows that EHM cases occurred this spring in California, Iowa, Indiana and Maryland, even amid lockdowns and shelter-in-place orders. Regardless of where and how it occurs, a single EHV-1 case that is not promptly contained can easily turn into a widespread outbreak that puts all nearby horses at risk—and if EHM develops, the fatality rate can be high.

In other words, even as public health measures to stop the spread of COVID-19 continue, now is not the time to let down your guard when it comes protecting your horse from the unique threat posed by equine herpesvirus.

Widespread yet insidious

EHV-1 and EHV-4 are respiratory viruses that, when inhaled, penetrate the epithelial cells lining the horse’s airways, setting off an inflammatory reaction called rhinopneumonitis, which is not unlike the common cold in people. Signs range from mild to severe and can include cough, fever, nasal discharge, loss of appetite and general malaise. Most sick horses recover uneventfully within a week or two with rest and supportive care.

“About 99 percent of cases occur in young stock,” says Nicola Pusterla, DVM, PhD, DACVIM, of the University of California, Davis. “Rhinopneumonitis is self-limiting and the horse gets over it. Foals, yearlings and 2-year-olds get it and overcome it, and that’s it.”

But like other herpesviruses, EHV-1 and -4 share a unique characteristic. Even after the horse recovers from his initial illness, the virus remains in his body in a latent form, “hiding” from the immune system. While latent, the virus may exist harmlessly in tissues, such as the lymph nodes. “Horses just continue to carry the virus for the rest of their lives,” says Amy Johnson, DVM, DACVIM, of the University of Pennsylvania. “The virus itself is everywhere in the equine population. The vast majority of horses are infected without any serious side effects.”

Yet when the horse is stressed—by travel, training or other major events—EHV-1 or -4 may revert to its active form and cause a new bout of illness. These later reinfections tend to be mild, even unnoticeable, but they pose a risk to herdmates. Sometimes a horse who is carrying the reactivated EHV will show no signs of illness at all, but he will shed the virus in his nasal secretions, potentially spreading it to others. If the horse is shedding a strain of the virus that is new to his companions, he may trigger an outbreak of illness. This explains how outbreaks of rhinopneumonitis can appear seemingly out of nowhere, even in a herd that is never exposed to newcomers.

“Unfortunately, a small percentage of horses are dealing with a different subset of this virus,” says Pusterla. There are multiple strains of EHV-1 and -4, and some are more dangerous. These strains of EHV-1 and -4 can pass beyond the respiratory membranes, infect white blood cells called lymphocytes and circulate throughout the horse’s body. If the circulating viruses gain a foothold in the epithelial cells lining the uterus of a pregnant mare, the resulting inflammation can reduce the blood supply to the placenta, which in turn can starve the fetus and may cause an abortion. If the infection occurs later in the pregnancy, the fetus may survive but be born weakened. The greatest worry with broodmare bands is that one mare shedding the virus may trigger an “abortion storm” as the infection sweeps quickly through the entire herd.

EHM occurs when the EHV-1 attacks the cells lining the central nervous system, damaging blood vessels serving the brain and spinal cord. “The neurologic impairment often doesn’t occur until a little bit later in the course of the infection,” says Johnson. Signs may include decreasing coordination, urine dribbling, weakness in the hindquarters and loss of muscle tone in the tail. The weakness in the hind-quarters may progress into a horse leaning against wall for balance, sitting like a dog or full recumbency with an inability to rise.

If the horse can be kept alive with supportive care, the inflammation will subside and the damage will heal—at least to some degree. Many horses recover fully and return to normal work, while others may survive with some permanent effects.

More severe cases—especially if the horse is recumbent—may be fatal. The statistics vary somewhat among different outbreaks, but on the whole, up to 30 percent of horses who contract EHV-1 during an EHM outbreak will develop EHM, and anywhere from 5 percent to 50 percent of those EHM cases may require euthanasia. In some outbreaks, the number of horses with EHM who were put down approached 80 percent.

Chances are, your horse is already carrying at least one strain of EHV-1, and should an outbreak occur in your area, there is no way to guarantee that he will not develop EHM. But you can take steps to protect his health—and the health of other horses. Here are five things you can do to reduce his risk.

1. Vaccinate but understand the limits of protection

The vaccine against rhinopneumonitis is listed as “risk-based” by the American Association of Equine Practitioners, which means vaccination is recommended for horses who are most likely either to be exposed to fresh outbreaks of the illness or to suffer the worst consequences from the exposure. Typically, this means broodmares, as well as horses who may be exposed to broodmares at breeding farms, and horses who travel frequently to competitions and other venues where they will encounter many other horses.

Vaccination is not a panacea, however. “Vaccination doesn’t prevent EHV-1 infection or EHM, but we still recommend vaccinating horses against EHV-1, based on risk assessment,” says Pusterla. “We know that vaccinated horses, if they do become infected, will likely have milder respiratory signs, and shed less virus, and may be less likely to transmit the virus to other horses or contaminate the environment.”

Several vaccines are currently available, based on either inactivated or modified live virus formulas, and your veterinarian can suggest one appropriate to your horse. Only two, for example, are labeled for use in preventing abortion in pregnant mares.

“Unfortunately we don’t have a vaccine that has a claim to reduce the likelihood of a horse developing EHM,” Pusterla says. “I am not sure we will have one in the near future.”

Even so, vaccination may offer some protection against EHM. “There are some vaccines that can help to reduce nasal shedding and maybe even reduce the level of virus in the blood, so they may decrease the odds of developing the neurologic form, but none have been proven to prevent it,” Johnson says.

There is no consensus about whether it is wise to administer booster vaccines to horses who are not yet sick when an outbreak occurs nearby. “There has been a lot of debate about whether or not horses in an outbreak should be revaccinated. The expert opinion has been split,” says Johnson. “There was a paper discussing [one recent] outbreak showing that the horses who had been recently vaccinated prior to the outbreak were actually more likely to develop neurologic signs than the horses that hadn’t been very recently vaccinated.”

If an outbreak occurs in your area, ask your veterinarian about vaccinating your horses. “The veterinarians here at New Bolton Center tend to not vaccinate horses that might have been exposed, but if someone is at a neighboring farm where they didn’t think any of their horses had been exposed, and they are worried that there might somehow be transmission, they could booster their horses to try to reduce the potential for spread,” Johnson says. “On a farm where there have already been horses exposed, we don’t recommend vaccination.”

Nevertheless, vaccination can help control EHM. “We still think vaccination is important, because by increasing resistance and decreasing nasal shedding, this probably can limit outbreaks to a certain extent, but no owner should feel that by vaccinating they are protected against the neurologic form,” Johnson says. “They are benefitting the equine population as a whole by reducing spread, but their horse is not necessarily protected from neurologic signs.”

2. Practice good preventive biosecurity

Vaccinating against EHV-1 and -4 is advisable, but doesn’t eliminate the risk of the disease. That means that the best way to protect your horse against EHM is to limit his exposure to horses who might be shedding this highly contagious pathogen. “It can be spread from horse to horse by nasal secretions, so if a horse is within 10 to 20 feet of another horse, coughing and sneezing, or able to touch noses or share feed or water sources, there is risk,” Johnson says.

The virus can also be passed from horse to horse via human hands and on clothing and shared tools and equipment. “In some outbreaks, even at equine hospitals, we’ve realized that even when we try to isolate horses, there can be fomite spread with people, unless they are really careful,” Johnson says.

Even when all of your horses are healthy, it’s a good idea to practice basic hygiene every day to avoid spreading any potential pathogens. “It’s similar to making a habit of washing your hands every time you go to the bathroom,” says Pusterla. “You want to engage in practices on a daily basis that reduce the likelihood of transmitting an infectious pathogen. Biosecurity entails the day-to-day ways of dealing with horses that we should all do.” Here are some basic rules:

• Prevent close contact with strange horses. Always maintain some distance between your horse and others at trails, shows, clinics and other venues. A distance of eight to 10 feet is best to avoid exposing your horse to airborne droplets.

• Avoid shared water and equipment. EHV-1 survives for hours or days on hard surfaces and, under the right conditions, up to a few weeks in water. Do not share water buckets or use communal troughs when away from home, and avoid borrowing tack or grooming tools. At home, make sure each horse in your care has his own feed and water buckets, tack and tools.

• Wash or sanitize your hands after working with each horse. Keep a supply of hand soap and/or hand sanitizers at your barn, and use them after handling each horse. Ask visitors to your barn not to go from nose to nose, petting each friendly face.

• Quarantine equine newcomers. Horses can incubate EHV-1 as well as other illnesses for a week or more without showing signs of infection, so it’s a good idea to isolate new additions to your farm for three weeks before allowing any contact with others in your herd.

3. Monitor at-risk horses

A necessary complement to biosecurity measures is vigilance in looking for the earliest signs of developing illness in a herd, and taking appropriate steps to control a potential outbreak. That means keeping a close watch on horses who travel and others who might be exposed to EHV-1.

One of the hallmarks of EHV-1 infection is a biphasic (two-phased) fever: The horse might have a low-grade fever as soon as 24 hours or up to six days after initial exposure to the virus. The temperature may then return to normal, but the horse will spike a new, higher fever six or seven days later. At that time he may begin showing other signs of respiratory illness, including coughing, loss of appetite, a depressed demeanor and nasal discharge.

During the time between the two phases of fever, however, the horse may show no signs of illness, and yet he may be actively shedding the virus—risking the health of every other horse he encounters. “This is one reason we tend to get outbreaks,” says Johnson. “There is often a chance that the sick horse exposed other horses before anyone recognized that it’s an EHM case. If people recognized the first fever and isolated the horse immediately, it would reduce transmission and the number of outbreaks, but this is really hard to do if the horse shows no outward clinical signs initially.”

That’s why it’s a good idea to monitor the temperature of any horse at risk of exposure to EHV-1 at least daily, or preferably twice daily. Candidates include horses who have recently returned from shows or competitions, as well as those who might have been exposed to sick horses during an outbreak.

“If any horse spikes a fever, even low-grade—anything higher than 101.5, or even 101—that horse should be isolated,” Johnson explains. “This will tend to slow or stop progression of the outbreak.”

Call your veterinarian as soon as you identify an at-risk horse with a fever. He may suggest simply isolating the horse and letting the illness run its course. If, however, there is a risk that other horses may have been exposed to a neurologic threat, your veterinarian may opt to run some diagnostic tests to distinguish EHV-1 infections from other illnesses, such as equine influenza. The definitive test for EHV-1 involves identifying the presence of the virus in a blood sample, nasal swab, or both using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to isolate the viral DNA.

PCR testing can also determine which strain of EHV-1 or -4 a horse might have. “A few years ago researchers determined the entire genome sequence of two different prototype strains of EHV-1,” says Pusterla. “One type is more virulent, leading to a more severe pathology within the infected horse. The more virulent strains of EHV-1 are more effective at replicating, leading to a higher level of virus in the bloodstream, which is more likely to affect the central nervous system.”

However, even when a horse is diagnosed with the less virulent form of the virus, he may still develop EHM. “The public often refers to [the two strains of EHV-1] as the ‘wild’ type and the ‘mutant’ form,” says Johnson. “If we look back at all of the reported outbreaks, about 80 to 85 percent of them are associated with the mutant form and the other 15 to 20 percent of the outbreaks are the ‘wild’ type. This is why people have used terms such as ‘neuropathogenic’ and ‘non-neuropathogenic’ to describe the mutant and wild types. This is misleading, however, because both forms can cause neurologic disease.”

The strain of the virus makes little difference in how the sick horse needs to be handled. “PCR tests can quickly diagnose whether or not a horse has the virus in the blood or nasal secretions and can tell us whether it’s the mutant form or the wild type,” Johnson says. “As clinicians, however, we don’t recommend doing anything differently in terms of which form a horse has. We still recommend isolation of the affected horse and managing it as a potential outbreak situation. We always assume that the horse is contagious and monitor all of the possible contacts with that horse.”

4. Isolate sick horses right away

“It is imperative, if you have a suspect or a confirmed case, to isolate that horse from other horses, to try to reduce transmission of disease,” Johnson says. “In the sport-horse world, there is a lot more effort now at the big shows to make sure they have isolation facilities on the premises or affiliated with the horse show. Then, if there is a case at an equine event, the horse can be quickly isolated—to try to prevent EHV-1 from spreading through the show-horse population there.”

Larger farms may maintain a separate barn and turnout area to house sick or exposed horses away from others, and they may designate staff to care only for the isolated horses. But there are measures you can take even on a smaller property to quarantine a sick horse:

• Move the sick horse to a stall at the end of the aisle, away from the main doors, and leave at least one empty stall between him and his nearest neighbor. Set up fans to direct airflow over the isolation stall outward, through an open door or window. If other people visit your barn, post signs asking them not to approach or touch the sick horse.

• Turn out the sick horse in a separate space. Ideally, you’d place the sick horse in a separate area that is downwind from the main pasture and does not share a fence. Another option is to use temporary fencing to cordon off an area of the main pasture, but you’ll need to make two barriers separated by about 10 feet to prevent contact between horses.

• Keep equipment separate. Designate a separate set of buckets and grooming tools to be used only with the sick horse; colored electrical tape is a good way to keep track of things.

• Care for the sick horse separately. Ideally, one person would care only for the sick horse while someone else did the chores for the healthy ones. If you’re the only caretaker in your barn, then care for the healthy horses first before approaching the sick one.

• It’s also a good idea to wash your hands and change your clothes after caring for the sick horse and before doing anything else in the barn. You could keep a spare set of coveralls for this purpose, or consider purchasing washable surgical scrubs or disposable protective gowns, latex gloves, shoe covers and other items like those worn by health-care workers. A footbath is also a good idea: Place a shallow pan with a bleach solution or a commercial disinfectant outside the stall to decontaminate your work boots as you exit. Placing a piece of AstroTurf or a rough-textured welcome mat in the pan will help to scrub the soles.

5. Disinfect the environment

After the sick horse recovers, it’s important to remember that the virus can survive for days on stall walls, buckets and other tools that were used to care for him—you’ll need to disinfect everything to avoid spreading EHV-1 to healthy horses.

“If there is a good thing about this virus, it’s that it’s not very hardy and doesn’t last a long time in the environment,” says Johnson. “It’s not like salmonella or clostridia, which live a long time and contaminate the environment for months or years. Usually, in most situations, EHV-1 lasts only about a week. Perhaps if it had perfect conditions it might survive for a month. Usually, the environmental contamination is easily dealt with just with time—taking horses out of that stall or barn for a few days, and routine cleaning.”

Nevertheless, it’s always a good idea to disinfect barn tools and other equipment periodically, and especially after caring for a sick horse. Any tool that comes in contact with a horse or his waste—including wheelbarrows and shovels, as well as grooming tools, hoof picks and buckets—can be sanitized with these basic steps:

• Scrape off any caked-on hair, dirt or grime.

• Add a squirt or two of dish or laundry detergent to a bucket of water and scrub tools to remove all dirt. Use scrub brushes on buckets, wheelbarrows and larger items.

• Rinse thoroughly with clean water.

• Soak the tools in a mild bleach solution or a commercial sanitizer, according to label instructions. (Check the labels ahead of time for safety precautions, and use rubber gloves and safety goggles to protect your skin and eyes.)

• Rinse thoroughly again with clean water, making sure no soap or chemical residues remain.

• Lay out tools in sunlight to dry.

In addition, towels and other fabrics can be disinfected in the laundry. Some washing machines have sanitization cycles that use steam or extra-high heat to kill even more pathogens. Sponges cannot be sanitized adequately; it’s best to simply discard and replace them when they get dirty.

Finally, it’s best to keep the horse home for three weeks after he recovers from the illness. Not only might he still be shedding the virus, but it takes time for the membranes lining his respiratory tract to fully heal after a bout with illness, and he will be more vulnerable to new exposures.

Outbreaks of a highly contagious and potentially deadly illness are always going to be frightening—and because the equine herpesviruses are so widespread among horses, the threat of EHM will never go away. We can’t eliminate this disease. “The way we can make a difference, however, is in the outcome, and to reduce the magnitude of an outbreak,” says Pusterla. “Early recognition, to act upon and hopefully reduce and minimize the outcome, is where we can all make a difference. The veterinarian is a key player, but horse owners, trainers, event organizers, farriers, etc., all play a role.”