When Romeo developed a minor cough in August 2017, I didn’t give it much thought. Having worked for the local equine veterinarian for nearly three decades, I knew dust-related coughing was common in our part of California during the summer. Plus, Romeo seemed perfectly healthy.

A gaited Appaloosa, Romeo was a good fit for me. When I bought him three years earlier, I hadn’t ridden in almost 20 years. But he made returning to the saddle easy and enjoyable. We had been exploring the acres of vineyards in our area and had even begun learning to negotiate trail-course obstacles. I looked forward to riding him for many years to come.

In September, I noticed some swelling on Romeo’s belly, with a small, oozing wound. The thought briefly crossed my mind that he might have pigeon fever, an infection caused by Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis bacteria. These organisms, which infect a horse via insect bites or open wounds, tend to live in hot, dry climates like ours, so we do see pigeon fever from time to time. An affected horse typically develops abscesses in the muscles of his chest, which then bulge like a pigeon breast. But Romeo’s swelling and wound weren’t anything like that. It seemed more likely that they were related to a run-in he and his pasturemate had with some hornets in our back pasture a few days earlier. The wound healed quickly so I thought the episode was over.

A month later, our community was turned upside down by the Redwood Valley Complex Fire. Wind and embers were blowing everywhere as the fire approached the ranch where Romeo was boarded. We evacuated him and his stablemate and took them to the Ukiah Fairgrounds, where they stayed along with 179 other horses for eight days. During that time, Romeo’s cough worsened. We thought the smoke from the fire might have exacerbated it and tried the usual equine cough remedies, including turnout and medication. Given all that Romeo had been through, I figured he just needed some time to recover.

In November, however, his cough worsened, and he started expelling chewed chunks of food. In fact, he coughed so hard he sprayed the barn floor with hay fragments. He seemed depressed and started to lose his appetite, dropping about 75 pounds. It was time to call the veterinarian.

The local veterinarian came out and listened to Romeo’s lungs. She thought she heard an abnormality in one section but nothing that would be of major concern. Romeo had a slight fever of 101.1, but it wasn’t high enough to necessitate doing bloodwork. The veterinarian floated Romeo’s teeth, in case the food chunks were a side effect of chewing difficulties. She also put him on a routine course of antibiotics. Romeo’s cough did subside and he stopped spewing chunks of hay. But, as soon as he was done with the antibiotics, both those signs returned.

As 2018 began, the same veterinarian returned for a re-check. Romeo had flared nostrils and coughed during exercise. In addition, his lungs produced rattling sounds. She decided to put him on the steroid dexamethasone and another 10 days of antibiotics. Again, his signs went away until the medications were stopped.

I decided to consult with my old boss, Michael Witt, DVM, who had moved to Washington State after that same fire took his home along with hundreds of others. Witt thought there might be a stricture—a ring of fibrous tissue—in Romeo’s throat and suggested an endoscopic exam to investigate that possibility.

On Valentine’s Day, I took Romeo to a large animal clinic about an hour from my home. The veterinarians there performed an endoscopic exam and found no strictures in his esophagus. They also did bloodwork and determined that most of his readings were within the normal range. The few that weren’t were so close to normal they didn’t raise concern. They gave us a few new drugs to try to quell Romeo’s cough.

A month later, there was still no appreciable improvement. Witt suggested trying Ventipulmin, a bronchodilator that could expand the small airways of the lungs, just to see if it would help with the cough. It didn’t. We were getting nowhere, and my beautiful, stoic horse was getting more and more depressed.

Finally, in April 2018, I took Romeo to the University of California, Davis for a full workup. The first thing they did was x-ray his lungs, and that revealed something important: cloudiness. A tracheal wash and bronchioalveolar lavage confirmed chronic inflammation, bacterial infection and reduced airway function.

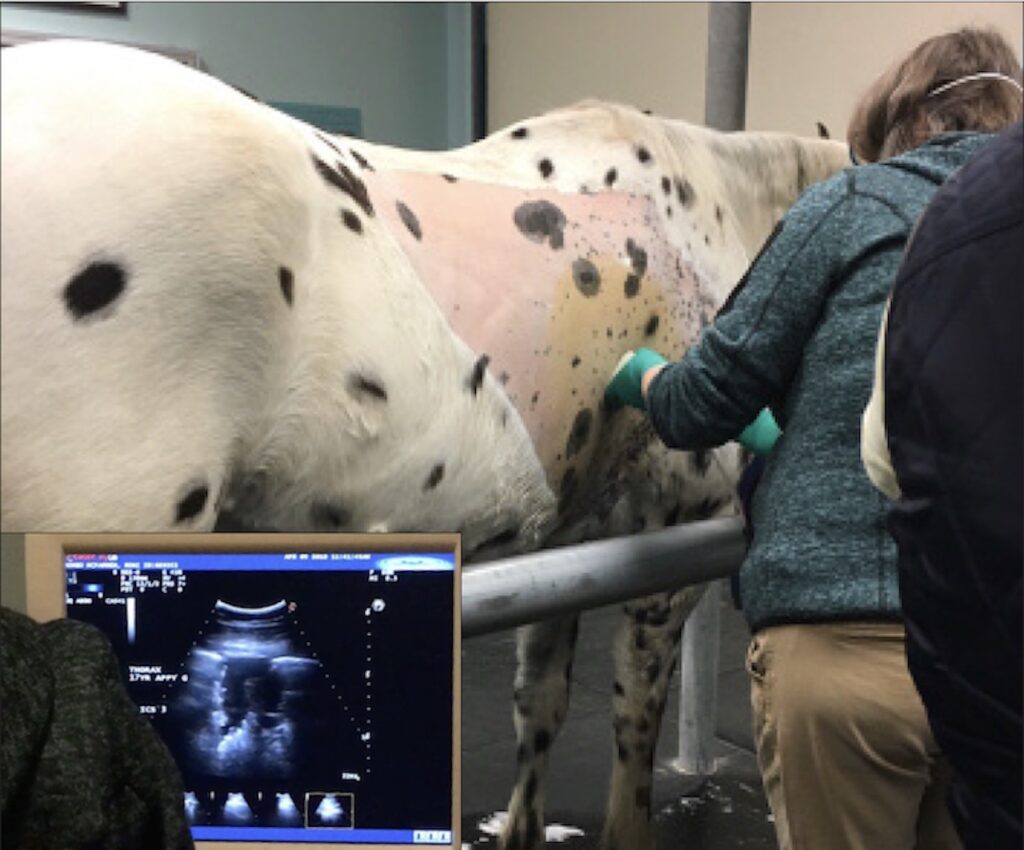

While all of this was being done, John Madigan, DVM, was reviewing the footage of the endoscopic exam performed by the first clinic. He thought the mucus visible in Romeo’s trachea was a significant clue and directed us to our next stop: the large animal ultrasound room. At this point we faced the possibility of either a lung tumor or an abscess. I was praying it wasn’t a mass, which could be malignant. As they moved forward with the probe on Romeo’s right side up his girth line, up popped on the ultrasound screen what I named “the black hole.”

It was an abscess. And it was big. There were most likely many of them, but this one jumped right off the screen at you. The clinicians perform-ed a needle biopsy, inserting a long needle into the abscess to remove a bit of fluid for testing. It is a tricky procedure and when they removed the needle, there was nothing in the syringe. Then, one of the lab workers noticed a tiny drop of pus on the tip of the needle. It was enough to test. The most likely diagnosis, I was told, was C. pseudotuberculosis abscesses in his lungs.

Six months after I discovered that swelling and sore I wasn’t sure about, testing confirmed what I had first considered: Romeo had pigeon fever. He hadn’t developed the extensive edema and abscesses just under the skin that would have given him the typical “pigeon breast” appearance, though. Instead, his abscesses were internal, where they went undetected as we searched for other reasons for his cough. Further complicating the diagnostic efforts was the fact he never developed a significant fever. About a quarter of horses with pigeon fever never do.

Click here to read more about Pigeon Fever.

Romeo stayed at UC Davis for a couple of days to get him started on the three drugs he needed, the antibiotics sulfadiazine-trimethoprim and rifampin and pentoxifylline, which improves blood flow. He would be on these drugs for at least two or three months. I was told he needed complete rest and that I was to watch for diarrhea, a common side effect of antibiotics. I added a probiotic to his diet to aid his digestion.

While Romeo was hospitalized, I went on the internet to learn as much as I could about pigeon fever. And what I found was not very encouraging. I read that only about 8 percent of pigeon fever abscesses go internal. Of those, it is 100 percent fatal if not treated. With treatment, there is still a high mortality rate of 30 to 40 percent. My daughter, wisely, told me to get off the computer.

We brought Romeo back to the ranch later that week and continued administering his medications twice a day. Because I live 20 minutes away from the ranch, I needed the help of my close friends Kitty and Mitzi. At this point, Romeo no longer looked sick even though he was still very ill.

In May 2018, as Romeo neared his 17th birthday, we went back for our first re-check after one month of treatment. I held my breath as the ultrasound probe found that big “black hole.” It was still there but when the technician measured it, we discovered it had shrunk about a centimeter. I was told this was good news and we should continue the drugs.

By now it was late spring and because his sides had been shaved for the ultrasounds, Romeo had to wear a blanket or a fly sheet for pro- tection from the sun. When we went back for a recheck in July, his hair had grown back enough that he’d been out of his sheet for only a week. My greatest concern, besides how the abscesses were doing, was that if he was shaved again he would be in a blanket all summer. That wouldn’t be comfortable in our 100- degree heat. By now, though, the ultrasound doctors had been taken in by Romeo’s charms and told me, “Because it’s Romeo, we will try without shaving him.”

It worked: They could visualize the abscess without any additional shaving, and what they saw was progress. The giant abscess seemed to be collapsing. The good news was the drugs were working. The bad news was that we needed to continue them until the next re-check.

By October, Romeo no longer coughed when he galloped, and you would never know he had been as sick as he was. His appointment that month revealed the abscess had filled in with what appeared to be scar tissue. He was good to go. After seven months on those three drugs, the regimen was finally ended and Romeo could slowly return to exercise.

Romeo and I picked up where we left off before that first cough. With his health restored, my gorgeous spotted guy can once again be the horse he wants to be and carry me through the vineyards and over trail obstacles for many more years.

Don’t miss out! With the free weekly EQUUS newsletter, you’ll get the latest horse health information delivered right to your in basket! If you’re not already receiving the EQUUS newsletter, click here to sign up. It’s *free*!