Home > Horse Care > A simple plan for fewer flies

A simple plan for fewer flies

- September 15, 2025

- ⎯ Laurel Scott

Spring has arrived at your barn—a welcome bit of warmth and renewal, no doubt, after a long winter. Far less welcome is the fly season that will soon follow, with all the associated swishing, twitching and agitation. Insects aren’t just a nuisance, though. They have the potential to transmit disease, stress horses to the point of weight loss and prompt enough foot-stomping to crack hooves and loosen shoes.

Our weapons against these pests are familiar. Year after year we all return to the same time-tested fly control methods—sprays, parasitic wasps and fly masks. Yet results vary. One farm may have a barely noticeable fly population, while another down the road is overrun. The difference, say experts, is not so much in the individual fly control components, but the overall strategy for deploying them.

Just as you might embrace holistic and sustainable approaches in other areas of your life, coordinating and streamlining the fly-fighting efforts on your property can boost your pest control game. This approach, referred to as Integrated Pest Management (IPM), can ultimately be more effective while being cheaper and less disruptive. All you need is a plan and the commitment to see it through.

Theory and practice

Integrated Pest Management is simpler than it sounds. “IPM is the use of multiple methods to maximize pest control while minimizing cost and risks to humans, animals and the environment,” explains Erika Machtinger, PhD, of the Pennsylvania State University’s Department of Entomology. “Coordinating all aspects of an equine fly control program in an organized, holistic manner is essential for maximizing effectiveness.”

Sanitation, habitat modification and chemical intervention

In practice, she says, that means structuring a fly control program so that the components, such as sanitation, habitat modification and chemical intervention, augment and reinforce each other. Under IPM, applications of pesticide can be more targeted, which reduces waste and the environmental impact.

Saundra TenBroeck, PhD, the University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences State Extension Horse Specialist, has seen the benefits of IPM firsthand. “I’m a huge fan of IPM on every horse farm, regardless of the size,” she says.

Reduction, not eradication

In her slideshow on external parasites for the UF’s Hippology Academy, TenBroeck lays out how IPM focuses on the reduction of pest populations to acceptable levels rather simply, using chemicals to try to eradicate them. “Pesticides are only one weapon in the arsenal of IPM practices. And they are typically used only after a number of other tactics have been tried,” she writes.

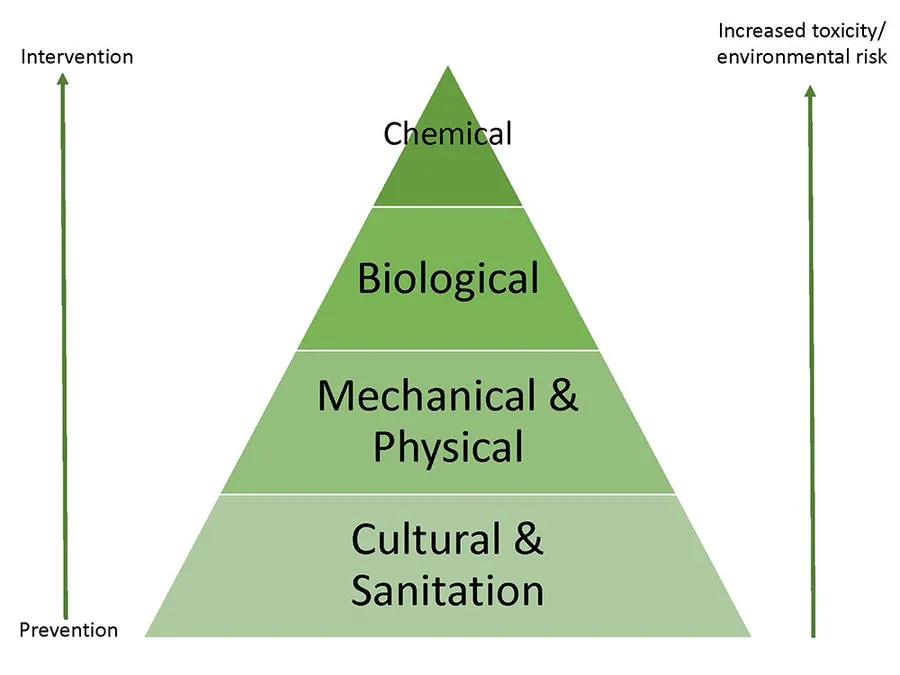

A popular method for visualizing IPM is a diagram similar to the Food Pyramid distributed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. At the foundation of the horse-oriented integrated pest management are sanitary measures, such as manure management, explains Machtinger, who has adapted the original IPM Pyramid for equine applications. Next, moving up the structure, are mechanical and physical measures, like window screens and fly masks, and above that are biological controls, such as parasitic wasps. Atop the pyramid are chemical controls—insecticides and repellents—products that will be more effective at lower volumes if the practices below them in the structure are implemented properly.

Machtinger emphasizes that monitoring is essential at every layer of the IPM pyramid. “Regular inspections to track pest populations helps determine when intervention is needed,” she says. “Although chemical controls—repellents and insecticides—are an important part of IPM, they’re used strategically.”

Your annual action list

Guided by the IPM pyramid, craft your own fly control strategy tailored to your horses’ needs and your situation. Ideally, you’ll start planning long before bug season, but even with a generous head start, you can’t account for everything. Each barn environment is different, and conditions and pest populations change over time. So, leave room for adjustment in your plan. With that in mind, these are the key components of an effective strategy:

1. Identify the pests most common in your barn, and research their life cycles and habits.

This first step in any IPM program feels a bit like schoolwork, but it’s worth the time and effort. “All baits, traps and some biological control methods are species-specific. So it is important to understand what you are targeting before you spend money on products that might not work,” says Machtinger.

Identifying species requires observation or perhaps some detective work. “Most flies have some easy-to-discern characteristics,” she says. “For example, if the flies are covering only the face in large numbers, those are generally face flies. If your horses are stomping a lot and moving around to avoid flies, those are usually biting stable flies.” If you’re stumped, check out the many resources available online or seek out professional help. “I always recommend contacting your local cooperative extension office,” Machtinger says.

2. Monitor the pest population levels in and around your barn.

Effective monitoring requires regular inspections and diligent record-keeping. One method is periodically counting adult flies caught in jug traps or sticky ribbons. Machtinger also suggests placing white index (“spot”) cards on rafters or eaves to capture fecal or regurgitation materials from flies. “In general, jug traps catching over 250 flies per week or spot-card counts over 100 are indicative of high levels of fly activity,” she says. “However, many of these metrics were developed for poultry and cattle facilities, so the numbers may need to be modified to your level of tolerance.”

It can also help to watch your horses at specific times of the day and document the number of fly avoidance behaviors like biting flanks, stomping, head nodding or shaking.

3. Set “action thresholds.”

Because some pests are worse than others, you’ll want to determine the point at which action against a particular species is necessary. If you were tending a commercial dairy operation, for example, fly activity that causes your livestock to produce less milk would be an action threshold—the point when additional control methods would be implemented.

For equine facilities, the comfort and welfare of horses are key components in determining tolerance levels. Even if your horse isn’t losing weight, for example, winged pests may be making him miserable—make a note of the numbers at which this threshold occurred, the types of insects present and the date, for future reference. Given that it’s preferable to intervene against flies before they become a problem, these records can help you start your plan earlier in the season in the following years.

IPM in action

Once you’ve identified the problematic pests and determined it’s time to act, consult the pyramid for the steps to take, starting at the bottom and working your way up.

Cultural and sanitation controls

The foundation of fly control is the management of the manure and soiled bedding where house and stable flies develop. This starts with mucking stalls daily. Machtinger also recommends adding a non-toxic drying agent like sodium bisulfate to your stall floors to reduce moisture. This has an added benefit of interfering with fly development by changing the pH of the bedding. In addition, you’ll want to keep feed rooms and aisleways tidy, promptly cleaning up any spilled feed.

Deposit manure and soiled bedding in an area some distance from the barn and implement a removal or composting program. TenBroeck recommends that “stored” manure be removed every four to five days in the summer and less frequently in cooler weather. If you can’t remove stored manure, you can cover it with a tarp to raise the internal temperature and make it unsuitable for fly development. Just remember to cover all the edges as well.

Don’t forget to pick up the manure from run-in sheds and areas in the paddocks or fields where horses congregate. Scattered hay mixed with urine and manure creates an ideal breeding ground for stable flies, and hay residue that appears dry on the top layer is often moist underneath when raked. If you can’t manage this additional cleanup daily, try for at least twice weekly.

Finally, take regular walks around your property to identify any standing water where horsefly and mosquito larvae can develop. Backed-up gutter drains and bird baths are easy to address, but other areas may not be. As TenBroeck says in her Hippology slideshow, “Many biting flies, including no-see’ums, black flies, horse flies and deer flies, breed in water or in mucky areas near ponds and swamps.” If your property has a pond or marshy area, consult with your local cooperative extension about appropriate methods controlling insect populations.

Mechanical and physical controls

The next level of the IPM pyramid encompasses everything from physical barriers—sheets, boots or masks that keep flies from landing on equine skin—to electronic “bug zappers” that lure and kill winged pests. This category also includes window screens and tarps that cover manure-filled wheelbarrows to keep flies from laying their eggs there.

In many cases, timing is key—and that’s where research into insect habits comes in handy. For example, if biting midges or mosquitoes are among your targets, you’ll want to keep your horses inside at dawn and dusk when these insects are most active. If face flies and horseflies are an issue, horses turned out during the day will benefit from fly masks and fly sheets.

On the mechanical side, electric agricultural fans in the barn will discourage flying pests. In addition, says TenBroeck, “traps [like sticky traps or CO2 mosquito traps] can reduce the adult fly populations.”

Strategic landscaping is another control TenBroeck recommends, because biting flies often rest in vegetation. Pruning shrubs, mowing pastures and clearing brush promotes airflow that can deter insects. If you have a green thumb, consider planting species like Asiatic Lilies or Bearded Iris around your barn. Their nectar attracts dragonflies, which eat mosquito larvae. If mites or chiggers are an issue, plant marigolds, sunflowers and geraniums, which are among the species that attract mite-eating ladybugs.

Biological controls

This level of the IPM pyramid generally centers on the early stages of the life cycle. Many biological controls target fly eggs and larvalstage insects, which are easy to kill. For example, parasitoid wasps, which do not sting or bite people or horses, lay their eggs in the fly pupae, inhibiting their development. These environmentally friendly predators are easy to deploy. They usually arrive packaged in the cocoon stage and are simply sprinkled on manure piles and other fly friendly areas, periodically throughout the season.

You can encourage other natural fly predators around your barn, too, including insect-eating birds, such as swallows, and mosquito-loving bats. But before hanging nest boxes or building bat houses, contact your local cooperative extension office to determine the species in your area and the best ways to cultivate them in your environment.

Chemical controls

Lastly, at the top of the pyramid, are chemical fly control products. Four types are used on horses and equine properties: repellent or insecticide products; residual or premise/space sprays; insect growth regulators/larvicides; and bait stations.

Insecticides kill the insects while repellents merely drive them away. Some products contain both insecticides and repellents, meaning they both repel and kill. Many products also include added synergists to increase the effectiveness of the active ingredients.

Oil-based or water-based?

Whether a formula is oil- or water-based also matters. Oil-based fly control products tend to last longer but can attract dirt and irritate sensitive skin. Water-based products dissipate more quickly in rainy conditions or when a horse sweats but are generally gentler on tender skin.

Residual pesticides are applied to structural surfaces around the barn, such as around doors, screens, rafters and anyplace flies congregate. Space sprays, meanwhile, are dispersed directly into the air to quickly eliminate flying pests. But, TenBroeck points out, space sprays have no lasting effect and must be applied more frequently.

Feed through products

Another chemical fly control option is feed-through products containing insect growth regulators (IGRs). The larvicide in IGR feed-through products is activated in the horse’s manure rather than his body, preventing the formation of fly larvae exoskeletons and thus inhibiting their development.

You may hesitate to add a larvicide to your horse’s feed, but Machtinger says their target isn’t your horse. “In terms of IGRs, we never use the term ‘safe’ because there are always exceptions. But IGRs are extremely low risk,” she says. “They target only developing flies in manure.” Still, says Machtinger, to achieve the best results, you’ll need to follow IGR product protocols. And, if you are a boarder, coordinate with other horse owners. “You need to rotate active ingredients, and every horse in the barn needs to be on the IGR,” she explains. “Sure, you may stop the flies from developing in your horse’s pile of poo. But if there are two, three, 10, 20 horses that are not treated, they are still developing.”

Bait products

Finally, bait products, which contain both an insect attractant and an insecticide, can help keep your horses comfortable. Whether formulated to be scattered in fly breeding areas or placed in stations around the barn, bait can knock down large numbers of pests within a short period of time.

As you juggle your horsekeeping chores, you may feel like integrated pest management is something you just can’t take on. But you’re probably already using most of the methods involved. Instead of an additional task or burden, IPM ensures those elements are deployed efficiently and effectively. Above all, IPM does more than just control flies. It helps make possible a cleaner, healthier future for your animals and your environment—and that’s worth the extra effort.