I’m not obsessed with manure, but like most horse owners it’s a part of my daily life that I pay attention to. I can recognize each of my horses’ individual manure piles, even in a shared pasture, and every day as I muck out I note their number, size and consistency.

So I immediately became concerned when I noticed that my black Saddlebred, Remington Steele, was passing loose stools. We were in the middle of an Arctic blast with temperatures never climbing out of the 20s, and I know that cold weather and an associated drop in water consumption can be a trigger for colic. But a new stock tank heater was keeping my horses’ water a tepid 50 degrees, and they were drinking well. And aside from upping their hay to offset the cold, I hadn’t made any changes in their feed.

I stayed home that day to keep an eye on Remy for signs of discomfort, reassuring myself that as long as he was producing manure, even if it was loose, I didn’t have to worry about impaction colic. It’s not the first time I’ve been wrong.

As the day wore on it was clear that Remy wasn’t himself. Usually a glutton for both attention and food, he was standoffish that afternoon and didn’t finish his lunch. By 5 that evening he was clearly uncomfortable, lying down and getting up repeatedly, so I hustled him into his stall and called the Pilchuck Veterinary Hospital equine ambulatory team.

Annie King, DVM, arrived just as it was getting dark. She gave Remy a thorough exam and found he had a mildly elevated heart rate and slightly decreased gut sounds on his left side. During a rectal exam she felt a large, doughy impaction in his colon, so she gave Remy fluids and electrolytes through a nasogastric tube and intravenous painkillers to keep him comfortable and help get the impaction moving. Before leaving, King told me that if Remy seemed comfortable and passed manure in the next few hours, he could have a very wet mash to eat. Otherwise, I was to call her if he showed any further signs of pain. She also left me with a tube of oral Banamine in case he needed more pain relief.

Three hours later, Remy had produced a small pile of wet manure and was banging his feed bucket, so I made him a sloppy mash of soaked pellets, which he cleaned up. When I went back out to the barn at 1 a.m., Remy was awake and restless. I took him out for a walk in the arena then returned him to his stall hoping he would sleep the rest of the night. But when I returned two hours later, he was clearly uncomfortable. After a bit of a fight I managed to give him a half dose of Banamine. (The other half ended up in my hair.) Another brisk walk produced a decent-sized manure pile, so I went back to the house feeling hopeful we’d turned the corner. But we were not so lucky.

By the time the sun rose, Remy was lying down and getting up repeatedly, so I called King back. When she arrived, she found little change from her first visit—Remy still had a mildly elevated heart rate and slightly decreased gut sounds on the left with a soft impaction that hadn’t moved much. She tubed him again with fluids and a laxative and administered another round of pain-killing drugs. She warned me that if Remy went down again, she wanted him brought in to the hospital for more aggressive treatment.

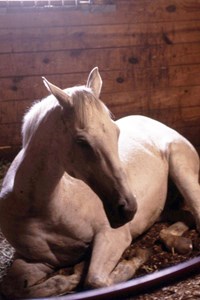

The drug cocktail worked its magic and Remy appeared quite happy, so at 9 that morning I turned him out into his paddock. Remy dozed quietly with his buddy Bravo for a few hours, so I went in the house to take a shower. Halfway through, I looked out the bathroom window to see Remy flat out on the ground, groaning, with his legs stretched out and shaking in pain. Hair dripping, I grabbed my phone and rushed outside to hitch up the trailer. I reached King and told her that I was bringing Remy in to the hospital.

No progress

Much to my surprise, Remy came off the trailer looking bright and lively. Wendy Mollat, DVM, DACVIM, was there to admit him, and she and King quickly escorted us into an exam room. While Mollat examined him, the Pilchuck staff took blood, placed a catheter for intravenous fluids and shaved Remy’s belly in preparation for an ultrasound and peritoneal tap. The bloodwork showed he was slightly dehydrated, and the ultrasound did not show anything unusual. I was relieved to see Remy’s peritoneal fluid come out a pale yellow—not bloody, which might indicate a ruptured intestine or other similarly catastrophic event—but the lab did find increased protein and white cells in the sample, a common finding in colon impactions. Another rectal exam produced a torrent of diarrhea, but also the discouraging news that the impaction wasn’t budging.

Remy was admitted to the equine intensive care unit, where he was given continuous fluids and regular doses of Banamine. He seemed comfortable and curious about his surroundings and all the people who came to his stall. When I returned that afternoon with a clean blanket for him, he greeted me eagerly and tried to follow me out the door when I left. I went home feeling certain that he’d clear the impaction overnight and be home the next day.

Remy did pass the night comfortably but produced only a small amount of diarrhea, and by the morning he was once again showing signs of distress. The fact that Remy was unable to clear the obstruction with aggressive medical treatment was a puzzle and a worry. Mollat was concerned that Remy would start to deteriorate if we let the colic go on much longer and suggested surgery. She asked if I was willing to go that route, and I quickly said “yes.” But, hoping to spare Remy the pain of surgery and my pocketbook a major hit, I asked if we could give him some more time to see if he could pass the impaction on his own.

Mollat said that since Remy was resting quietly for the moment and wasn’t showing signs of shock or sepsis, we could give him a few hours. But she reminded me that if we were going to do colic surgery, sooner would be better than later. I went to work feeling like I was going to colic myself as I agonized over sending Remy to surgery, but in the end he made the decision for me: At 2:30 that afternoon he went down on his knees in acute pain, and I gave my go-ahead for the procedure.

Remy’s surgery was done by James Bryant, DVM, DACVS. I stayed to watch through a viewing window. After Remy was anesthetized, the team hobbled and hoisted him up on an overhead trolley, then gently guided him onto the surgery table and attached him to a ventilator and monitor. After the team of interns scrubbed Remy down, Bryant neatly made an incision along the underside of his barrel and begin to unwind the yards of Remy’s intestines.

Even my unpracticed eye could see how heavy and tight his colon appeared.

Working quickly, Bryant and the surgical interns decompressed Remy’s colon, flushing out all the impacted material. Standing on my tiptoes I could see Bryant paying particular attention to one part of Remy’s colon, cutting away what looked to me like a large blood clot—a mass of dark red, gelatinous tissue. This worried me, but I hardly had time to dwell on it. Bryant and his team worked so quickly that within an hour and a half they were suturing Remy back up, then hoisting and trolleying him back into the padded recovery room.

Bryant immediately came out to talk to me. Remy’s colic was, as they suspected, caused by an impaction in the left ventral colon. But what they had not expected was the discovery of a mass on Remy’s pelvic flexure—the point between the left and right colon where the gastrointestinal tract drastically narrows and turns 180 degrees. Bryant said the mass resembled a submucosal hematoma, a pocket of blood from a burst vessel, but we would have to wait for the pathology report to know for sure. I went home, but as exhausted as I was I didn’t sleep until Mollat called to tell me Remy had recovered safely from the anesthesia and was stable.

Remy looked remarkably well the next day. He nickered when I arrived and guided me to a particularly itchy spot on his side so I could scratch it for him. He seemed content in the clinic, where every two hours “visitors” stopped by to monitor his vitals, administer medications and keep his intravenous fluids flowing. Over the next day he was slowly started on softened pellets and small amounts of soaked hay. The techs also took him out for hand-grazing twice a day. Four days after surgery his appetite had returned, and, more important, he was regularly passing manure. I have never been so excited to see poop. It was like each pile was a stamp on his passport out of there.

Meanwhile, the histology report on the tissue removed from the pelvic flexure of Remy’s colon came back. The mass, I was told, wasn’t a hematoma but an accumulation of inflammatory cells, mainly white blood cells with a predominance of eosinophils. One type of specialized white cells found in peripheral blood, eosinophils are rarely seen in the gastrointestinal tract. Based on their presence in Remy’s mass, the veterinarians made their diagnosis: He had colicked because of idiopathic focal eosinophilic enteritis (IFEE).

A new disorder

I hadn’t heard of IFEE before, but I quickly got a crash course in this rare condition. IFEE is classified as an inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), a type of disorder characterized by the abnormal accumulation of white blood cells in the intestinal wall.

In the case of IFEE, the lesions are “focal,” meaning that they develop in distinct locations, as opposed to spreading over a larger area. IFEE occurs in two forms—circumferential mural bands (like a rubber band wrapped around the intestine) or plaques (irregular masses on the intestinal wall). Like other IBDs, IFEE tends to appear primarily in the small intestine (enteritis), but in rare cases like Remy’s the lesions can develop in the small colon or in the pelvic flexure of the large colon (enterocolitis), the places where the gut is at its most narrow and most vulnerable to impaction.

While other forms of IBD tend to be chronic conditions that show vague signs such as weight loss, diarrhea, fatigue, and mild, recurring colics, IFEE seems to be an acute process that shows very clear signs something is wrong: The growing lesions may cause partial or complete blockages that quickly lead to painful colics. In addition, inflammation at the site of a lesion interferes with gut motility and impedes a horse’s ability to pass an obstruction. The good news is that once the lesions are surgically removed, horses have a good prognosis for complete recovery.

Mollat told me that IFEE was virtually unheard of before 1999 and, while it is still relatively rare, its increasing occurrence as a cause of colic in horses has caused some researchers to label it an emerging disease. No particular breed, sex or age of horse seems predisposed to IFEE, and cases have been reported in the United Kingdom, Ireland and the United States. Interestingly, a condition similar to IFEE occurs in humans—eosinophilic gastroenteritis—and incidence of that disease is also reported to have risen in the last decade.

Because of the involvement of eosinophils, which are associated with inflammation, both food allergens and parasites have been investigated as the cause of IFEE. But the focal nature of the lesions makes allergy unlikely, and no evidence of parasitic involvement has been found. Furthermore, studies have shown that the vast majority of affected horses had not experienced any changes in feed, and most were on a regular deworming program. If IFEE is like eosinophilic disorders in other species, it could be caused by a misfiring of the horse’s own immune system—a hypersensitivity triggered by an environmental insult, a defect in the immune system or a combination of both. But, for now at least, IFEE will retain its “I” for “idiopathic”—a disease without a known cause.Researchers are still working to understand IFEE. In some of the case reports, horses had multiple IFEE lesions throughout the small intestine—one horse had 18—but obstruction occurred at only one site. This raises the possibility that some horses may develop IFEE lesions but never show outward signs.

Another question that remains unanswered is how quickly IFEE lesions arise, and how quickly they resolve on their own. Pathological findings suggest that most lesions are at least three days old at the time of surgery, and in several cases where horses required a follow-up procedure, veterinarians discovered that IFEE lesions had disappeared on their own, some in as little as two days after the initial surgery.

One study following 28 horses with IFEE found that all recovered after surgical decompression of the impaction without removal of the lesion, findings that suggest the disease is transitory. Some researchers have suggested that the use of corticosteroids could shrink the lesions and perhaps eliminate the need for surgery, but such treatment is problematic: You can’t treat every impaction with corticosteroids on the off chance it might be caused by IFEE, and for now the only way to be certain a horse has one of these lesions is to find it during surgery.

While others will continue to seek answers about IFEE, Remy’s role in this medical mystery is over. His recovery from the surgery was quick and uneventful. After seven days in the hospital he was discharged. Over the next week, I slowly returned his diet to normal, with an emphasis on laxative foods like alfalfa and fresh grass. Following Mollat’s recommendation, I started him on a daily dewormer. I also followed instructions to keep him confined to his stall for four weeks, followed by another month of limited turnout in a small paddock, and finally four weeks of full turnout with no riding or forced exercise. When he was finally cleared to return to work, I think he was a bit disappointed. He seemed to have enjoyed his time as a pampered patient.

My own emotional recovery from this episode is more uncertain. A born worrywart, I can’t help but hover over Remy, reading his manure piles like tea leaves. But with no clear cause for his IFEE I am left feeling a little helpless. Studies indicate that IFEE lesions don’t recur, but because the disease is poorly understood there’s no guarantee.

I’ve always practiced preventive measures for colic—feeding multiple small meals instead of a few large ones, offering plenty of fresh water, and keeping my horses on turnout 24-7—but now I’m extra cautious. I scrutinize every flake of hay for weeds and mold, and I avoid feed changes as much as possible so Remy is not exposed to potential allergens. I know I can’t police everything that goes into his mouth, and at some point I have to let him go out and graze the pasture and be a horse, but I don’t anticipate giving up my vigilant poop patrol anytime soon.

This article first appeared in EQUUS issue #441.