At graduation time, our thoughts turn to education. What are students learning these days–and how are they learning it? Are students better educated in some subjects than they were in the past, or is technology just enabling different delivery methods of the same information?

Speaking of delivery systems, did you ever think about how people–especially artists and veterinarians–have learned the anatomy of the horse over the centuries? In many cases, they learned by dissecting horses, and at many veterinary schools, they still do, although other systems are employed as well.

The great artist and anatomist George Stubbs was known to haunt the slaughterhouse and hang partially-dissected horse cadavers via block and tackle in his studio so he could pose them in different gaits and postures in order to draw them more realistically than other artists could.

In pursuit of his art, he also contributed to the body of knowledge about the anatomy of the horse.

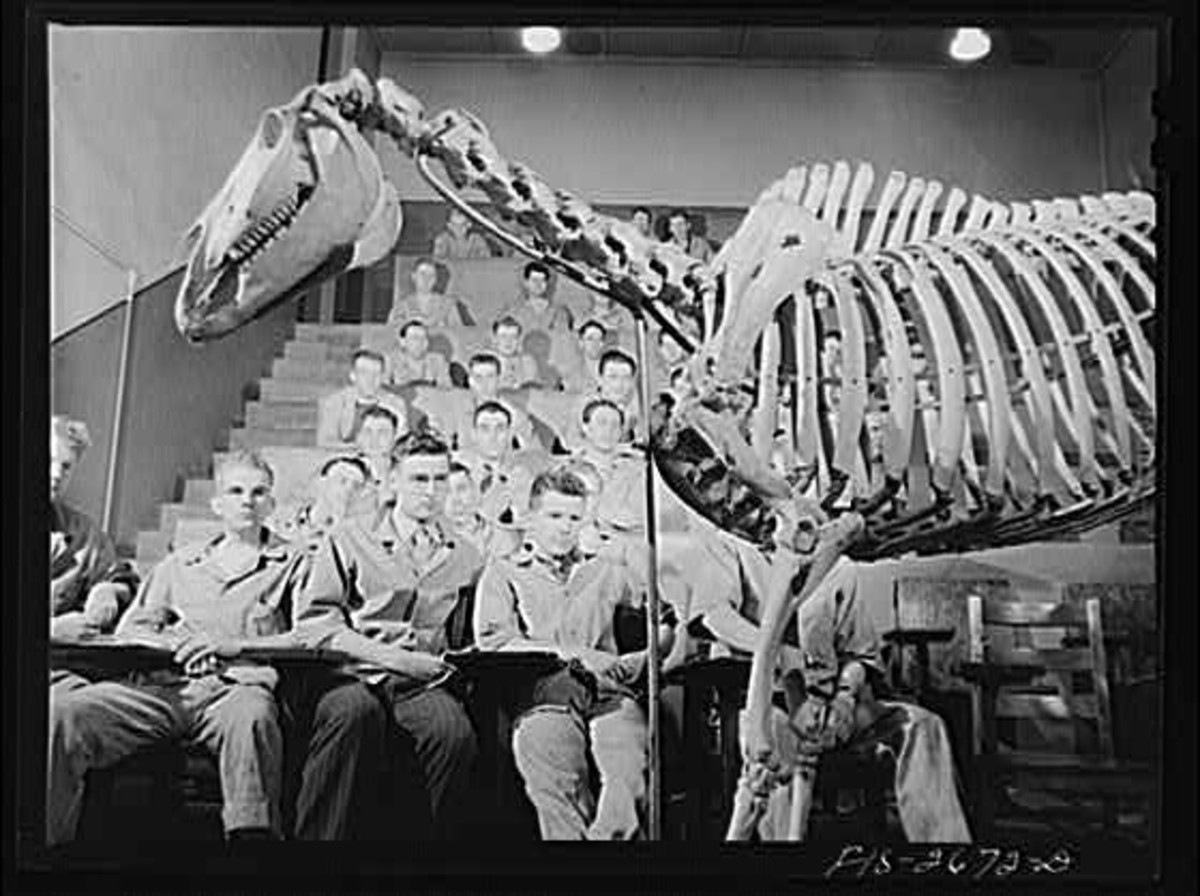

But in veterinary schools, the teacher didn’t always have a deceased horse on hand, and there was little refrigeration. So they had clever ways to teach their students.

In the first video (below), you see an anatomical teaching model of a horse, previously used in the University of Liverpool’s School of Veterinary Science. It’s now on display in the Tate Hall Museum at the Victoria Gallery and Museum in Liverpool. Models like these were common in vet schools; the organs might be constructed of wood and expertly painted; some of the most exquisitely detailed ones are actually made of papier mache.

The Liverpool anatomy model is basically a giant puzzle that fits together perfectly. An organ could be removed for students to examine. Was the test at the end of the semester the challenge of assembling the entire model–or perhaps building your own?

How do animal science and veterinary students learn anatomy now? The best way seems to be a combination of the most low-tech and high-tech methods. Books are still the first line of study, but it is difficult to show anatomy in three dimensions on a flat page. Dissection is still done, but growing opposition to the practice has sent vet schools looking for more sophisticated alternatives.

One of the great tried-and-true methods is the “coloring book” approach. It sounds juvenile but there is something psychologically tricky at work when you use colored pencils to fill in structures. Many people find that if they lay the point of the pencil on the deep digital flexor tendon and they actually follow the tendon from the muscle at the top of the leg to its final attachment on the coffin bone in the foot, their brains will “click in” on that structure. It’s what we call “sticky” learning. Try it, and see if it works for you!

And if you have any old anatomy books, you might notice that some of the anatomy plates are “colored” by hand. This was done by the student owner of the book. As the pencil went up the leg, the student could recite all the attachments and origins of a ligament or tendon. It works!

Also on the low-tech side, students need to be able to identify the anatomical landmarks on a living animal whose shape and size may be very different from a laboratory model.

Fast forward to some of the very advanced teaching tools available today, such as the ability to build 3-D models of bones and study them in the comfort of our own computers.

In 1999, the University of Georgia College of Veterinary Medicine introduced an animated computer-generated equine limb. “The Glass Horse: Elements of the Distal Limb” program, created a maneuverable model that could be manipulated in three dimensions (you can even look at the bottom of the foot), while adding and subtracting layers of nerves, blood supply, tendons, ligaments and integument (skin and hoof).

This is a coffin bone from a horse’s foot, rendered a three-dimensional object through the use of the Blender app for Macintosh computers.

Why stop with just one bone? Biomechanicist Jonathan Merritt at the University of Melbourne in Australia animated the entire distal limb anatomy.

Jonathan Merritt was a PhD student at the University of Melbourne in Australia when he decided to experiment with computer rendering and animation to create a simple model of the horse’s lower limb. When he posted it on YouTube, the video found many fans and admirers who use it for all sorts of educational purposes.

A new technique called plastination allows anatomy professors to preserve body parts or structures and make them available to students to study. The horse’s foot is used extensively this way; students can compare the anatomy of five or ten or twenty feet, side by side, and learn what the inside of a foot looks like when a condition or conformation causes a deformation or injury. Veterinarians and farriers use the encased “slices” of hoof tissue to illustrate conditions to horse owners.

Similarly, they can study slices of healthy vs diseased organs or soft tissue structures in the limb. There is even a set of plastinated blocks of the horse’s lower limb simulating the “slices” seen in an MRI.

So, students now have a variety of ways to study anatomy, and the best system probably varies widely between individual learners. We all have different ways in which we learn best–by listening, by studying, and even, in the case of Equinology’s success, by feeling.

The days of staying up late, hunched over a black and white anatomy book are long gone, but those books still serve an important role. We have never understood anatomy in a more complete way–or been reminded of all we still have to learn.