Home > Horse World > King of the Wind: Marguerite Henry’s long-ago gamble

King of the Wind: Marguerite Henry’s long-ago gamble

- May 15, 2025

- ⎯ Lettie Teague

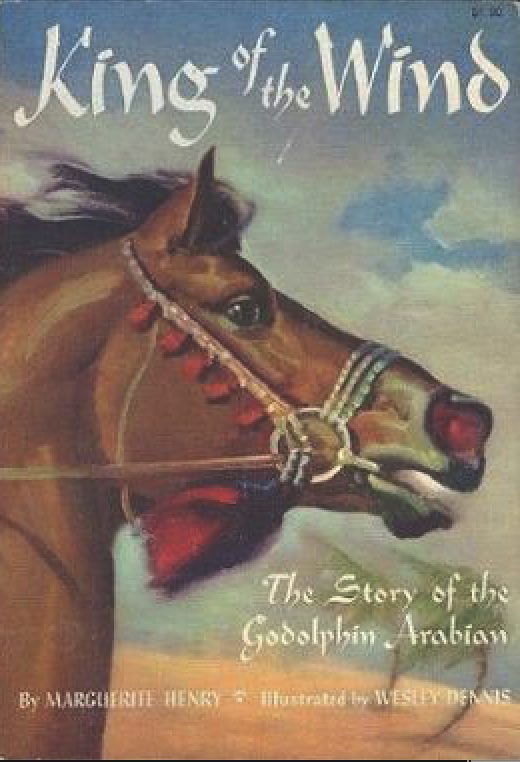

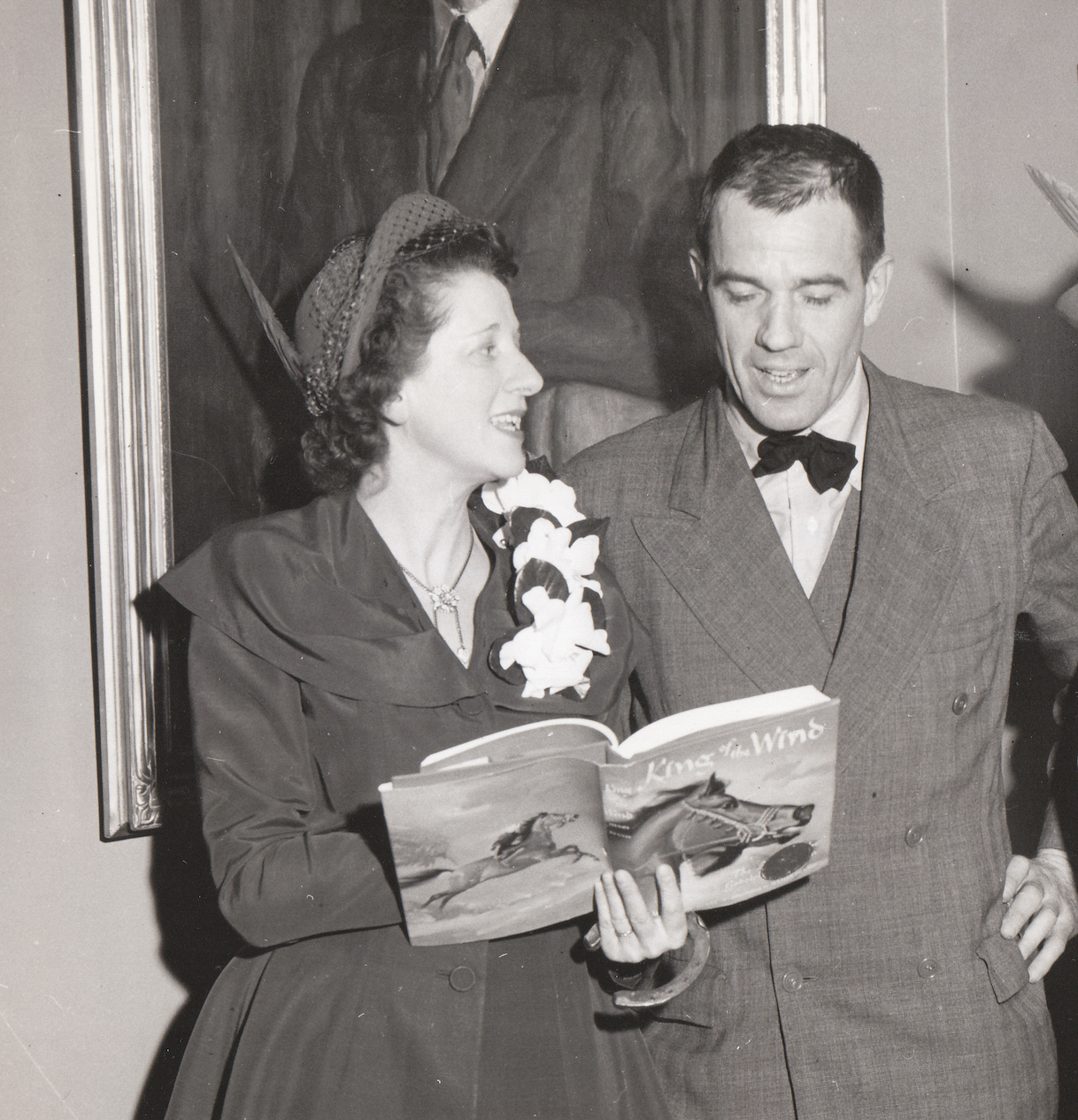

Marguerite Henry had been thinking about the Godolphin Arabian, a progenitor of the Thoroughbred breed, for quite some time—long before she wrote her beloved bestseller Misty of Chincoteague. It was, in fact, on a trip to work on that book that she first discussed the Godolphin Arabian, with artist Wesley Dennis.

Years earlier, Walter Chrysler, the auto magnate, asked Dennis to draw a portrait of the stallion as a letterhead for his stud farm stationery. Chrysler was not only the founder of the eponymous automotive company but also an avid horseman and Thoroughbred breeder.

When Dennis asked his assistant to research a portrait of the Godolphin Arabian for the Chrysler commission, he learned of the remarkable story of the foundation sire’s life. Before the Earl of Godolphin of Cambridgeshire, England, recognized his greatness, Sham (the horse’s original name) was abused and neglected by various owners. He even spent some years as a cart horse in Paris. Dennis believed he and Marguerite could bring the story to life in a book. Soon after he described the Godolphin Arabian’s history to her, Marguerite, too, became obsessed with the idea of telling the story. But it took time to transform the idea into reality.

In The Illustrated Marguerite Henry, Marguerite described the obsession with the stallion’s story she shared with Dennis even as they worked on Misty. The Godolphin Arabian remained ever-present in their minds until they finally convinced their publisher, Rand McNally, of its worth.

A Cinderella story

The story of the Godolphin Arabian had a Cinderella-like quality. A poor boy cares for a downtrodden horse who turns out to be one of the most consequential stallions in equine history. Despite this seemingly perfect combination, Marguerite faced resistance from her publisher, as well as family and friends. They collectively argued that Marguerite’s last few books—Justin Morgan, Misty and Benjamin West—had been successful, well-received, all-American tales. Thus, it made sense for Marguerite to stick to the same formula. She had a huge audience of avid readers for such books. Why did she and Dennis care so much about a horse born so long ago and so far away? Who among her young readers cared about Morocco, or for that matter, could even find it on a map?

The questions continued. But Marguerite was undaunted. She decided to tell the story from the perspective of Agba, the mute boy who cared for Godolphin Arabian. But this would be a challenge. How would that work? What kind of gestures would he make? Writing about the Godolphin Arabian would require extensive and time-consuming research. Even if Marguerite could pull it (all) off, would the book even sell?

Deviating from the formula

Any best-selling author who deviates from a tried-and-true formula faces this sort of skepticism. But the resistance Marguerite encountered made her that much more determined to write the book. She read dozens of books about the 18th century, seeking to understand the Godolphin Arabian and the people around him. What made them happy? How did they feel? What did their world look and smell like? She wanted to feel and to taste and to see things as they had. “I read every day and every night until these ghostly people assumed substance and began to take me into their confidence,” Marguerite wrote in 1969’s collection of letters to fans, Dear Readers and Riders. She had to find a way into her characters’ thoughts—and their hearts. “I began to see the Earl of Godolphin not just an aristocrat who owned a stable of pleasure horses. His passion was horses, blooded horses,” Marguerite wrote.

Living history

For her research, the author reached out to scholars, librarians, historians, horsemen and theologians. Although a list of “books and authorities consulted” appears on the last page of King of the Wind, Marguerite noted it was merely a partial source list.

Meanwhile, Marguerite covered the walls of her study with images that helped connect her to the places and people in her book. Along with photos of thatched-roof houses and the wigs of French nobility, she hung portraits of Arabian horses, stable boys and the Earl of Godolphin “magnificent in his cascade of ruffles.”

Marguerite wanted readers to deeply feel King of the Wind. As she worked, she wanted to live the story as well. Marguerite acted out Agba’s work and his heartbreak as she was going about her barn chores.

As she described in “The Story Behind the Godolphin Story,” in her newsletter (No. 2): “Even at noon when I set aside my work and went out to water my own horse, I was still in the past. It was not his eyelashes that brushed my hand as I held the water bucket but those of Sham, the fleet one. And so the anguish of writing was washed away because my story characters completely took over my life and the here-and-now grew dim.”

Ahead of its time

King of the Wind was more daring than Marguerite’s previous books, and perhaps any of the books that followed. The story not only took place hundreds of years earlier in places that few people had traveled to or even knew much about in the 1940s. Marguerite also tried to place herself in the shoes of a poor Arab boy who was as harshly treated as his horse. It was a remarkable act of cultural sensitivity achieved by a middle-class, middle-aged white woman living in a small, conservative town in the Midwest in the mid-twentieth century.

Marguerite wrote a complex story of dark moments and suffering as well as hope restored. Even when Sham triumphed—his worth recognized by all—the innkeeper’w wife still called Agba “a varmint-in-a-hood.” The illustrations by Dennis matched Marguerite’s prose—by turns joyous and heartbreaking.

The final scene

Dennis and Marguerite discussed at length the final scene of the book, which features Dennis’s illustration of the Godolphin Arabian being presented to the Queen. The ceremony never took place, but Marguerite wanted the details to align with the known history of the time. She visited the Chicago Public Libary to confirm the color of the Queen’s dress, the livery worn by the groom, the color of the grass.

“Of course, the Queen would be gowned and plumed in purple,” Marguerite wrote in The Illustrated Marguerite Henry. And since her research revealed that the Earl of Godolphin’s stable colors were scarlet and blue, the Dennis illustration shows the footman attired in these hues as he holds Sham’s bridle.

Across the page from this beautiful piece of art, Marguerite expressed Agba’s triumphant unspoken thought: “My name is Agba. Ba means father. I will be a father to you, Sham, and when I am grown, I will ride you before the multitudes. And they will bow before you and you will be King of the Wind!”

Published in 1948, King of the Wind won the Newbery Medal—the most prestigious award in children’s book publishing. It also became a bestseller, reprinted multiple times. The book later inspired a movie (1990) and Breyer models. But King of the Wind never came close to the popularity of Misty of Chincoteague. Was the story too exotic? Was it too hard for children to relate to so much suffering and the pain? In many ways, perhaps, King of the Wind was a book ahead of its time.

Adapted from Dear Readers and Riders: The Beloved Books, Faithful Fans, and Hidden Private Life of Marguerite Henry with permission from Trafalgar Square Books, TrafalgarBooks.com