Surprising findings about rare navicular condition

- February 24, 2025

- ⎯ Mick McCluskey, BVSc, MACVSc

A study suggests that a rare malformation of the navicular bone that often results in chronic lameness is congenital rather than related to wear or injury.

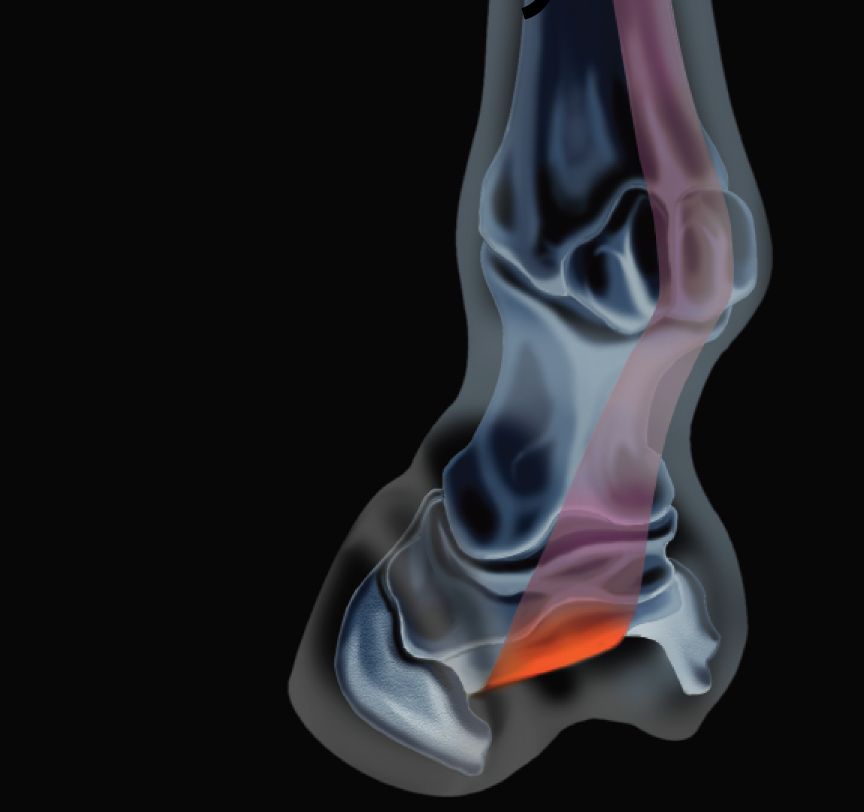

Researchers from Utrecht University in the Netherlands and Ghent University in Belgium recently published a paper documenting three cases of navicular bone partitions—meaning the bone is composed of two (bipartite) or three (tripartite) sections instead of a normal, single structure. These sections are delineated by defects in the bone, covered by smooth cartilage, and range from shallow dents to full-depth separations connected only by fibrous tissue. In each case, the unusual formation was discovered through radiographs taken to investigate chronic lameness.

Click here to learn what behavior may indicate lameness in horses.

These abnormalities are often mistaken for fractures or other injuries, but they would actually be present at birth, says Willem Back, DVM, PhD, DECVS. “At around 100 days of pregnancy the navicular bone is still made up of cartilage, while at 3 to 4 months of age, the bone starts to become fully ossified,” he says. “We think that during the transformation process from cartilage to bone, the partitioning of the navicular bone develops from a disturbance of the local vasculature.” Supporting this theory is the fact that the partitioning usually develops in two specific locations, a third of the width of the bone from either end, where vessel groups serving the area converge.

Partitions weaken the navicular bone, Back says, making it susceptible to overload as the horse grows and enters work. In response to stress, the bone may develop cysts as damaged areas begin to die. These changes may initially go undetected, he explains, but eventually result in some degree of lameness.

“We think these horses develop lameness when there are more structural, degenerative changes becoming apparent in the bone,” says Back. “In cases of a more advanced cyst formation, most likely this will result in a chronic lameness.”

He adds, however, that if the condition is discovered before the horse becomes lame, there are ways to try to preserve soundness. “A conservative therapy can be initiated using NSAIDs, corrective farriery and a restricted exercise regimen,” Back says, “but obviously still with a poor prognosis. A surgical intervention, such as a neurectomy, is not advisable, as this would even accelerate the cyst formation and increase the chance of the horse developing even a pathological navicular bone fracture.”

This article first appeared in EQUUS issue #468, September 2016.

Don’t miss out! With the free weekly EQUUS newsletter, you’ll get the latest horse health information delivered right to your in basket! If you’re not already receiving the EQUUS newsletter, click here to sign up. It’s *free*!