Year of the Horse: Will it mean the end of horses in New York?

- March 10, 2017

- ⎯ Fran Jurga

Do you believe in ghosts How about the ghosts of horses? How about the ghosts of more than 300 years’ of worth of horses?

You didn’t even have to be a believer to see it. There it was, larger than life. Larger than any horse we’ve ever seen on earth.

A giant horse flashed above the mobs in New York’s Times Square on New Year’s Eve. It was all part of corporate publicity for publishing giant Thomas Reuters, whose marketing executives surely didn’t connect the dots when they chose their image.

The horse, depicted in a painting by renowned Chinese horse painter Yuan Xikun, was chosen as an image for New Year’s Eve in Times Square because, after all, when the ball dropped at midnight, the world sequenced from 2013, the Year of the Water Snake, to 2014, the Year of the Horse.

A sequence of three of Yuan Xikun’s horses stood there above the square, looking out over the masses at the corner of 42nd Street.

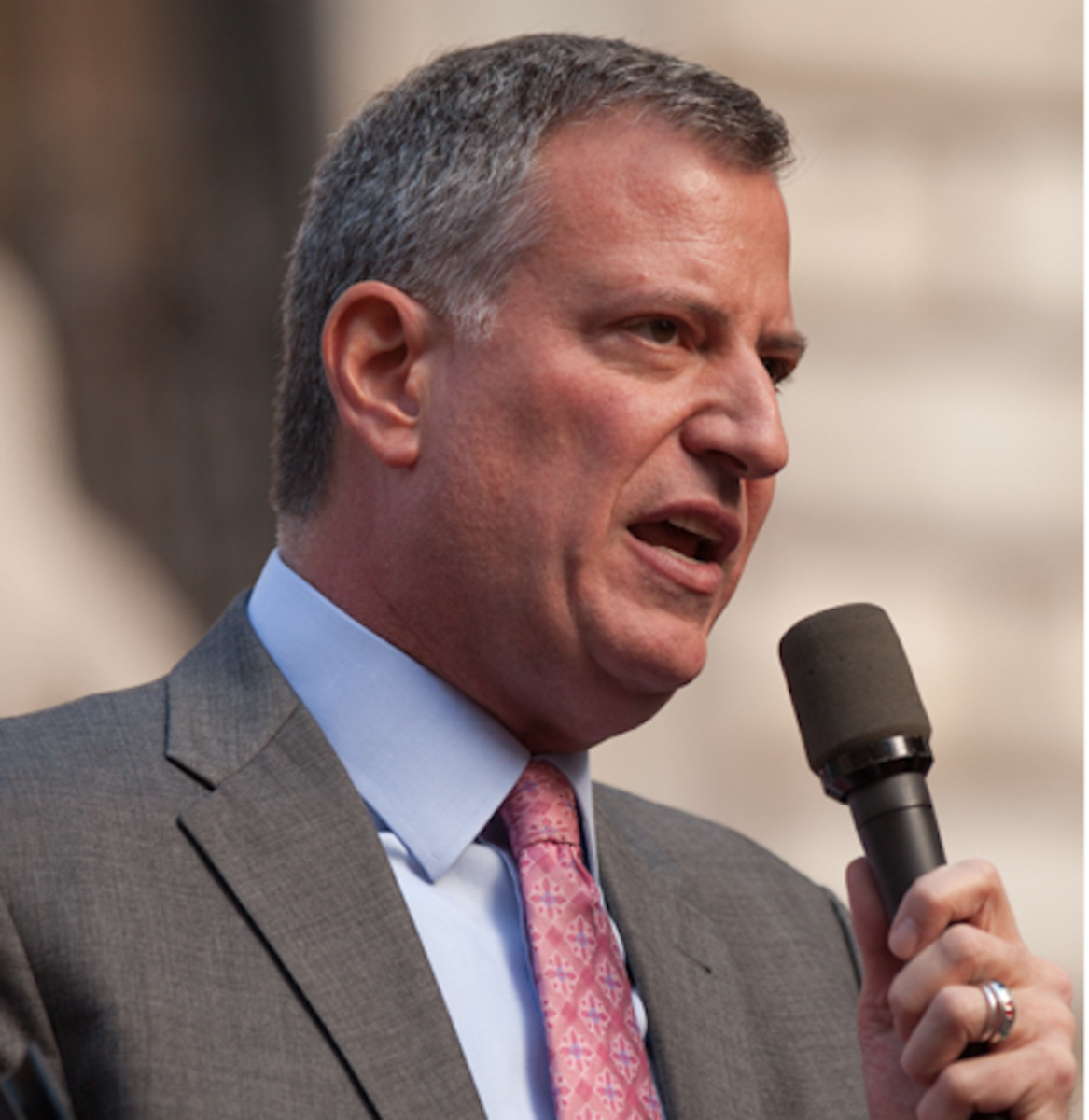

How will New York City usher in the Year of the Horse? According to most predictions, it will be the Year of No Horses in Manhattan. New mayor Bill de Blasio has pledged to end the iconic carriage rides in the Central Park neighborhood.

It’s a small issue on the agenda of one of the world’s great cities, but few issues have been so bitterly fought. Nor have two sides of an issue rarely been so unable to galvanize their cases to the public. Most people wonder, Is it really cruel? Is it really safe? but there are no easy answers. The public wants that easy answer.

Across the country, equestrian journalists and publications have been dodging taking a stand on this issue, since endorsing the ban seems like a shot to the heart of horses, and opposing the ban seems like tacit approval of what may be unsafe work conditions or inferior care for horses.

This much we know: Whatever happens in New York under de Blasio will be a harbinger for horses in other cities and for horses who work, in general.

Let’s look at some history:

At the height of the horse-drawn age in New York City, 130,000 plodded through the streets of New York. Times Square’s first residents were horses. Before there was a New Year’s Eve party there, Times Square was a horse farm; Revolutionary War General John Morin Scott bred horses on what is now 43rd Street. Horses were even more at home in Times Square when Brewster Carriage Company led a migration north. Almost the entire carriage trade followed, along with thousands of workers who wanted to live near their employment.

In the great heyday of carriages, Times Square was known as Longacre Square, named for the famed district of London where royal carriages were designed and constructed. The big year was 1896, when William K. Vanderbilt built the massive American Horse Exchange in the neighborhood.

But almost as soon as it was built, the Exchange burned to the ground. From the New York Times archives: “crazed animals could be seen dashing blindly about in their terror.” One account stated that the crowds that formed actually prevented horses from getting out of the building. Those that did escape were found throughout the city. The death toll was estimated at 60 of the 265 horses stabled there.

But Vanderbilt rebuilt the Exchange to be even bigger and better. It was an icon of Manhattan social life; ads for the New York Horse Show identified horses that had been purchased through the Exchange. When the carriage industry could no longer hold onto the real estate of Times Square, Vanderbilt sold his giant stable to the Shubert empire of urban theaters.

As horses were pushed out of the city and into Central Park, their comings and goings from stables became part of the eccentricity of a powerhouse urban center. In concrete canyons, clip-clopping hooves echo.

Is it safe, though? Is it right? Are these horses “happy”?

“I didn’t see a single horse that didn’t show all the signs that we associate with contentment,” is the now-famous quote of former AAEP President Harry Werner after inspecting the carriage horses for welfare concerns.

They may not be unhappy, but they may be in the way. Widespread charges of mixed interests on de Blasio’s part suggest that getting horses out of Central Park sound like so much mudslinging for those outside the city.

They also may not be “safe”. Proponents claim that only three horses have died on the job in the last 30 years. Opponents say that it three too many. Car-horse collisions are tragic and traumatic to horses involved and bystanders who witness the wrecks.

On the sensational side, reports that the 200+ carriage horses would go to slaughter are simply inflated. The horses are not a mass work force; they have individual owners, who would individually determine what the future of the horses would be.

How many will be standing with neatly combed manes and tails, behind white fences, in lush green pastures?

Probably about as many racehorses that actually find caring homes when they leave the track. In other words: not many.

What jars so many about the controversy in New York is that it has been going on for so long, and that opponents are only willing to accept a complete ban. New York City’s carriage horses are possibly the most regulated horses in the world. Even their vacation time is mandated.

For those of us who travel to less prosperous places in the world and see horses working in deplorable conditions, the debate over New York’s horses seems like injustice to less-fortunate horses that need help desperately. Dollars spent to get the horses out of Manhattan (or to keep them there) could do great good in the hands of groups like The Brooke Hospital in Cairo or World Horse Welfare. The cart horses in Soweto would gladly trade places with a New York carriage horse.

Regardless of which way this turns out, I hope that people will think of the less fortunate horses in this world who have few or no advocates, no Facebook pages, no fundraisers, no lobbyists. They just get up every morning and go to work. No one’s fighting over them, or fighting for them.

At least as long as the fight goes on, people are thinking of horses. When and if the horses are banned, they probably won’t be thinking of horses at all.

If the horses are banned in New York, I suggest that some money be raised to track them. Microchip these horses or somehow ID them so they can be found a year from now, five years from now, a decade from now. See what happens to them.

They’re safer right where they are; but in this age of the “unwanted horse” the most unwanted of all seem to be horses whose owners do want them. It’s their neighbors who object.

No easy answers, and no easy way of backing down means that the carriages could spend the Year of the Horse parked outside a courthouse.