Thirst for Knowledge: 100 Years Ago, Horses Suffered When Veterinarians and City Officials Disagreed

- March 10, 2017

- ⎯ Fran Jurga

Cleveland had 200 of them. Washington, DC had 153. The ASPCA privately funded over 100 in New York City alone, while the city funded many more. They were the pride of American cities, and symbolized the largesse of generous citizens concerned for the well-being of horses.

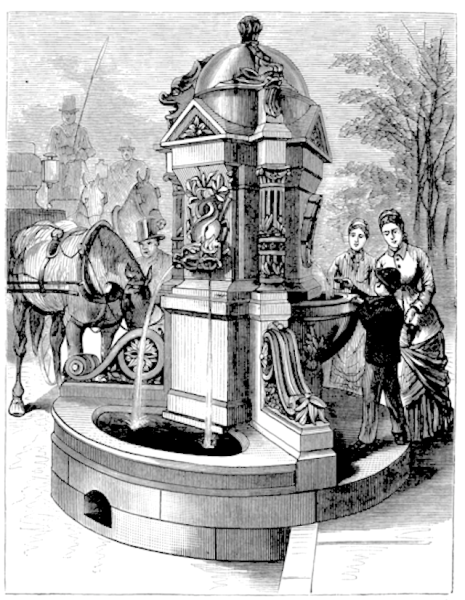

At the turn of the last century, American cities opened their water pipes to the working horses on the streets to insure the horses were well-hydrated to do their job. Cities provided the water, and horse lovers’ donations provided the fountains and troughs filled with it.

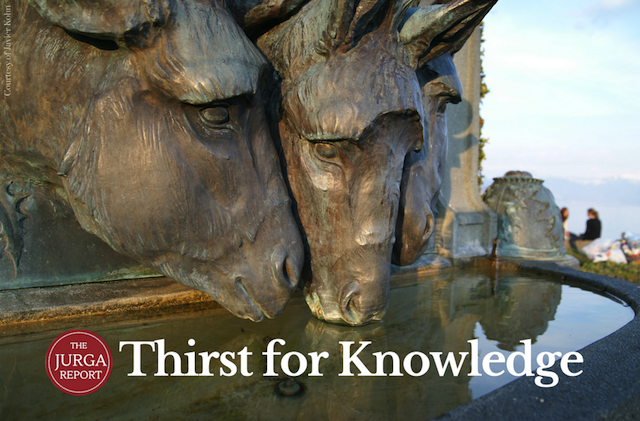

Designs for horse troughs and fountains became a grandiose artistic statement for inspired architects whose fountains sometimes looked like scale models of ornate temples. Since horses hitched to wagons needed many feet of clearance from different angles to allow multiple horses to drink at once, the fountains and troughs were placed in intersections. City planners created spacious plazas around the fountains , and the paved open spaces preserved some architectural breathing room in the increasingly crowded and overbuilt cities.

Cities were proud of their fountains, and boasted how many they had. Many were donated as memorials to animal lovers, and conveyed the reverence of cemetery statuary. Some had lanterns held high aloft. Others had sculpted lions and rearing horses. The ornamental details and deep shadows of some looked like they would scare even exhausted work horses away.

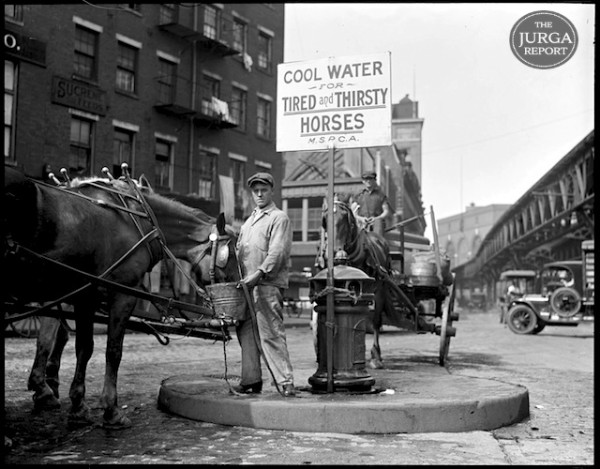

But when an epidemic of glanders hit some cities soon after the turn of the century, public health officials ordered the horse troughs to go dry. By 1914, pulling the plugs on horse fountains was a national movement. Some cities, like Boston, ripped the beautiful fountains out and replaced them with hydrants. Teamsters were told to siphon off water into pails and offer it to horses instead of allowing horses to drink at their leisure.

Other cities simply turned off the taps and made no contingency plans. The horses were on their own.

Glanders was (and is) an “epizootic” disease, meaning that it can be passed from horse to human. Human infection is rare, but the disease meant a bullet for the suffering horses long ago. Cities wanted to take no chances. But some veterinarians thought otherwise of the closure plans, and a war of words between public health medical officers and veterinarians and even between veterinarians ensued.

And across the country, humane society volunteers hit the streets, buckets in hand.

Who knows where the controversy began, but it hit the headlines in September 1909, when Missouri State Veterinarian Dr. D. F. Luckey, an expert on the spread of hog cholera, publicly condemned water troughs at the Interstate Association of Live Stock Sanitary Boards. Veterinarians called on public health officials across the country to support their call for a ban because troughs and fountains were putting humans at risk of glanders.

Even at this first public announcement, another veterinarian begged to differ. Dr. J.M. Wright, State Veterinarian for Illinois, a veteran of animal diseases at the Chicago Stockyards,was quoted as saying that water troughs bore no public health risk to humans or horses if the water was kept running.

But Luckey had the last word, stating emphatically that over 1,000 horses had died from glanders in Massachusetts the previous year. And he blamed it on the ubiquitous horse fountains in that state’s cities and towns.

It was a warning that sounded like a bona fide threat, and city officials in the audience took note. But when they went home and attempted to implement the ban, they found they had opened the Pandora’s Box of equine welfare issues.

Across the country, sanitation officials had to make up their minds: should they close the fountains or not? When the California state veterinarian, Dr. Charles Keane, called for closure of his state’s fountains, counties in the southern part of the state, particularly around Los Angeles and San Diego, refused. Female advocates for the horses lead the revolt, saying that the closure would be harmful to horses, since lazy teamsters would not bother to get down and water the horses with buckets, or refill them if they spilled the water.

Keane had to give up on the plan for the urban areas in the south, even though mules exported from California ranches had infected ranches in Hawaii with glanders, according to that state’s 1909 Department of Agriculture Report.

In Massachusetts, the city of Boston didn’t just close the fountains, it dismantled them. They kept the plumbing in place and installed hydrant-like water taps. Massachusetts had the highest incidence of glanders in the United States, although not all states were keeping count. Massachusetts counted about 1000 cases of glanders each year in the first decade of the 20th century. According to the 1904 Annual Report of the State Department of Agriculture, three people in Massachusetts died of glanders in 1903.

But the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (MSPCA) would not accept the decree of the city’s powerful Department of Animal Industry. MSPCA went directly to the Water Department to establish horse watering stations at hydrants in the city of Boston.

While the humane societies’ first concern was to make sure the horses in their cities had a source of water, they also mounted a national publicity campaign to discredit the veterinary advice that closed the fountains. Instead, they recommended that American urban officials look across the ocean to London to see how matters were handled there.

In London, glanders had been addressed proactively. It was a front page issue in 1892, when the city passed the “Contagious Animals Act,” which included the “Glanders or Farcy Order”. Broadsides posted around the city warned horse owners that they would be fined for not reporting a case of glanders.

But it would be a book by William Hunting, FRCVS, president of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons and editor of the Veterinary Record, that resonated with American horse advocates. Glanders: a Clinical Treatise would be the instant ace up the MSPCA’s politcal sleeve. Like some American veterinarians, Hunting also endorsed the running water concept, but he had facts and figures on hand, and put the blame on the movement of diseased horses rather than on the fountains and troughs.

He wrote:

“It is quite possible that some cases of glanders have arisen as the direct effect of drinking at a public trough but they are very few and far between. I have an intimate knowledge of the stables of three contractors who had had, during the last 20 years, four outbreaks of glanders in their studs.

“Each outbreak was clearly and directly traceable to the purchase of a horse from an infected stud, and was stamped out at once without spreading. Save these outbreaks no glanders have troubled them, and yet their horses travel all over London, and drink at any water trough they can reach.

“I feel convinced that infection from water troughs is very rare, because (in) 90 percent of all outbreaks which I have personally investigated, other methods of infection were traceable.

“The harm resulting to horses from being denied water all day would cause a mortality greater than is caused by all the glanders in the metropolis.”

Hunting’s words carried weight. Thanks to London’s Metropolitan Drinking Fountain and Cattle Trough Association and the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, London boasted nearly 1,000 public water troughs. A half million times a day, a horse or cow took a drink from a public water trough or fountain in London.

Hunting’s book was music to the ears of the American humane advocates.

The MSPCA surveyed the 426 veterinarians in their state. Of them, 59.4 percent were against the closure of the fountains. “Suffering for water outweighs the risk of glanders,” the pro-fountain vets said. Horses need water throughout the day in hot weather, and depriving a horse of water for nine or ten hours until it is home and ready to be fed is not only depravation, it may cause colic.

Also on the table was the argument that poor teamsters had no running water in their primitive stables and sheds where so many city horses spent the nights. These drivers depended on public watering opportunities for their horses to have access to any water at all.

And was one pail of water enough? Would drivers in a hurry provide the multiple buckets that a thirsty horse required? When a horse inhaled deeply at a trough, just how much water did it drink? When a horse spilled its bucket, would the driver bother to refill it? If troughs were a risk, what about drivers who shared buckets between horses?

In New York, the Times covered the controversy of the water fountains on the front page next to politics and news from the war in Europe. The ASPCA hired a full-time horse trough maintenance employee to keep the fountains and troughs clean.

In Philadelphia and New York, the cause was taken over by women, as it was in California. They formed crews at hydrants and filled bucket after bucket. The Women’s Pennsylvania SPCA recorded watering horses more than 700,000 times in 1914, and was the first organization to purchase a traveling water wagon to take water to the horses. Soon, Boston had two water wagons, and impassioned fundraising pleas to match.

As the controversy progressed, facts came forward that helped clear up misunderstandings about the disease. Buffalo, for instance, had 200 fountains, all with constantly flowing water. There were no cases of glanders in that city.

In April 1916, the city of Philadelphia backed down. Officials decided that the health risks to water-starved work horses indeed did not warrant the small risk of glanders. In a political compromise, the city turned over the maintenance of all its fountains to the Women’s Pennsylvania SPCA. But at the same time, across the state, Pittsburgh was threatening to close its fountains. Humane advocates appealed to the mayor, since there were no cases of glanders in the city at the time.

Cincinnati closed its fountains, and in 1916 had an outbreak of glanders anyway.

Perhaps this story should have a happier ending than it does. There is no question that glanders is a deadly and serious disease. It was raging in Europe among the war horses in France, while the Americans were appealing to keep their troughs open. At the time, some Americans were still alive who could remember the disaster that befell the Giesboro horse depot outside Washington, DC during the Civil War, where more than 11,000 Union horses died from glanders in 1864.

Not only the Union suffered. At General Lee’s horse depot in Lynchburg, Virginia, 6,875 horses contracted glanders. The depot could only supply 1000 horses to the Confederate cause during the war; 3000 horses died, 449 were shot and the rest were left unusable.

A conspiracy theory of the day suggested that the North intentionally brought glanders-infected horses to the South, and used the disease as a weapon of war to compromise the mobility of the Confederate forces. With an eye to glanders, General Robert E. Lee revamped the policy of private ownership of Confederate soldiers’ horses so that he could control the health and well-being of the four-legged forces he desperately needed.

Among Hunting’s claims was that the United States military had controlled its high rate of glanders during the Spanish-American War in Cuba by shipping the infected horses home and selling them at public auction, where they continued to infect stables full of vulnerable horses, and leading to the increase in non-military horses infected in the early years of the century.

Americans had a right to be wary when it came to glanders. But the fight to keep the fountains would have long-term effects on the health and well-being of city horses. While most historians place the demise of the horse in the city at the feet of the automobile and truck, there is also much to be asked of the “which came first?” variety.

The loss of the fountains and troughs was tantamount to the loss of infrastructure. The fountains were never rebuilt. Horses became more difficult to care for; the horse’s requirement for water was something that teamsters had to think about and plan for in advance each day. If the overall health of city horses declined, the motor vehicle looked more attractive for a reason that few have ever considered.

Around the same time, smooth-paving of city streets to accommodate motor vehicles became a danger to horses who slipped and fell on the smooth surfaces that replaced the cobblestones sized to fit their calks. How to prevent downed horses on slippery streets would join the closing of the water troughs as a welfare campaign for the humane societies.

Never underestimate the power of fear and uncertainty. It was the age of all-out capitalism, and business must proceed at any cost.

Most of the beautiful fountains and troughs in our cities disappeared, although a few were converted to other purposes, or put in storage. Some have been restored, like the magnificent Cherry Hill Fountain in New York’s Central Park. Water flowed again there in 1998. That city excavated the magnificent Robert Ray Hamilton Fountain from where it was buried 12 feet deep in Riverside Park in 2008, even before the Broadway play would make anything about the Hamilton family in Manhattan so dig-worthy.

In Boston, the art-deco “Lotta’s Fountain” on the Charles River Esplanade, donated by silent film child star and horse lover Lotta Crabtree, will be restored this year. She was a vice-president of the MSPCA and left money for the horses to drink.

Water is important to horses, and it has played an appropriately crucial role in the history of urban horses in the United States. Did the lack of it accelerate the demise of those same horses?

The next time you walk past an old horse trough that is now used as a flower box, give it a rub. You won’t catch glanders, honest. But now you’ll know how and why the water ran out, and that it never came back.

• • • • •

Check back soon and often for more news. Grab the RSS feed (top of article) for your reader or Feedly, or check my Facebook page, follow me on Twitter, or leave a comment below to share your thoughts.