What the world needs is a better mousetrap. Or so the saying goes. If you were to ask around the horse world, the answer would be different. A cat will take care of a mouse. What we really need are better options to help support horses who become unstable or need help because of orthopedic injury, neurological disease or overall weakness.

Slings have many uses in equine emergency services and hospital care. While occasionally a horse may be suspended in a sling for weeks at a time when recovering from a serious injury, many horses are in slings for short periods of time. Not only are orthopedic injuries looking for the ultimate sling; slings are very useful for horses that have neurological disorders or diseases like West Nile Virus or even the neurological form of Equine Herpes Virus.

You may think of slings as high-priced emergency equipment relegated to critical care, but the concept of slings is an ancient one in the horse world, and even today there are multiple types of slings for different purposes. You just don’t see them very often, and horseowners should be thankful if they never see their horses suspended in one.

What’s their story?

Slings are not just the marvels of engineering that you may see in a veterinary college or equine referral hospital. Many farms utilize more casual makeshift slings, especially when the residents may suffer from laminitis or even infirm older horses that need help, particularly for treatment or grooming.

Using a belly sling to life a horse–or prevent it from bearing all or some of its weight, which is not always the same thing–seems to be a basic principle of physics. The abdomen joins the front and hinds of a horse. Lift it in the middle and the feel will leave the ground.

That much is true, but the construction of the animal’s vital organs need to be protected. Prolonged use of a sling must take into account what the pressure and/or compression has done to the organs.Some horse lean forward in a sling, putting more weight on the chest.

Continued pressure on the hide and skin where the weightbearing stresses the straps of a sling will likely cause irritation and even lead to sores if not monitored and medicated.

And then there are horses who just don’t want to be in a sling, and could even hurt themselves or their handlers. While the benefits of slings surely outweigh these negative attributes, the possibility of a sling being detrimental to a horse exist, and they are why so many veterinarians are cautious about prolonged use of a sling for a horse with a long-term therapy ahead.

• • • • • •

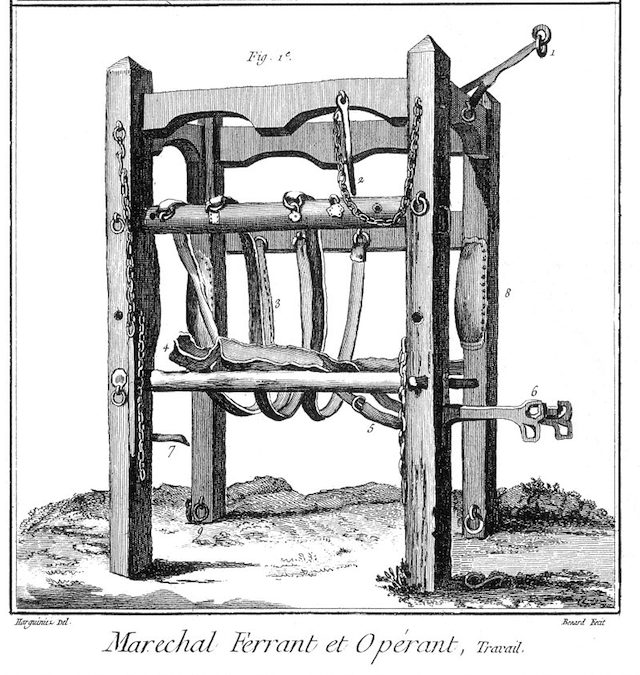

One of the most simple uses of a sling, and probably the source of much that we know about slings, doesn’t even come from horses. Before the invention of hydraulic tilt tables to trim the feet of dairy cows and especially to shoe the hooves of oxen, a simple stock or “crush”, as it is called in some countries, with a sling was used. In France, these stout frames with slings are called “travails” and were outdoors; many still remain in villages and rural areas as a testament to vernacular architecture of the most basic kind.

Cattle and oxen find it difficult to support their massive bodyweight on just three legs, and they can be difficult to control so a device needed to be used to both stabilize them and get their feet off the ground so they could be lifted and trimmed or shod. Using a sling in combination with stocks, one or two people could easily get the work done, instead of requiring a crew to restrain the animal for a prolonged period of time.

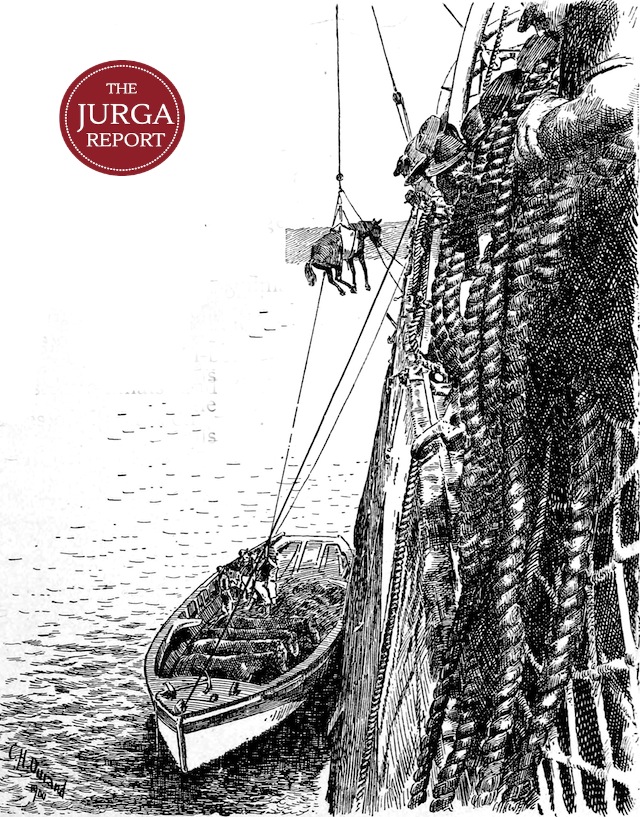

Did horses arrive in North America in a sling? Many sources credit a hoist-type sling from the deck of a Spanish ship as the mechanism used to get horses ashore when the Spanish explorers and conquistadors arrived. But moving horses by sling was a tedious, time-consuming and dangerous task. The horses may have been loaded from the dock in Europe that way, but unloading them in Mexico or the Caribbean was another matter entirely.

When the United States Cavalry needed to get its horses to Cuba during the Spanish-American War, they found no docks. They pushed the horses overboard. To their surprise, the horses didn’t swim to shore; in one account, the horses drowned. In another, they swam out to sea, instead of toward the shore until a bugler on the beach fixed that by blowing “Right Wheel.” The obedient horses turned and swam to the beach.

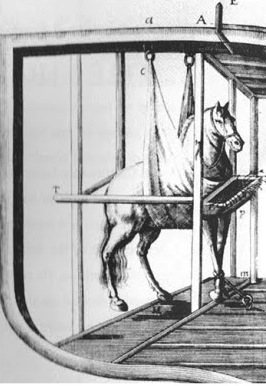

Many ships that transported horses were equipped with slings in the 19th century. A Canadian patent in 1878 describes an elaborately-engineered sling system for the equine passengers. But the British, who were learning a lot by transporting horses to India and South Africa, found that the horses fared better without slings, since the slings prevented them from swaying with the ship.

It’s interesting that several recent patents have been filed for advanced sling systems in horse trailers.

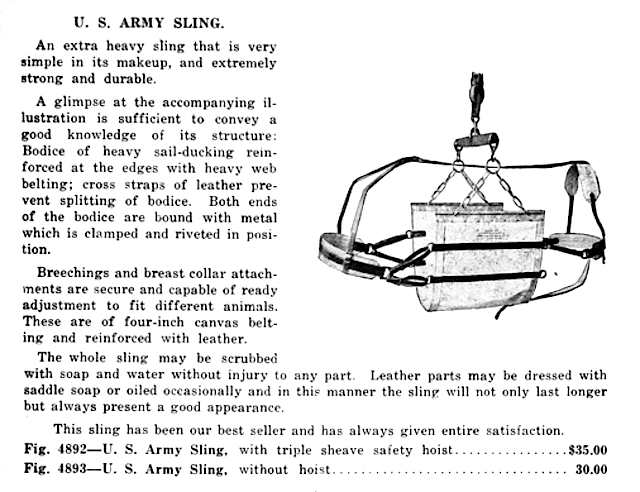

Slings are often shown in old veterinary journals and books, but their use was limited to cases that could be treated in time for the sling to be of use, and the slings were often homemade. The US Cavalry issued a complete sling set up with all the hardware needed to every post, according to General Carter in his book. Over the years, horseowners and trainers continually re-invented the sling with different pulleys and straps; people who had never even seen a horse in a sling suddenly wanted to design a better one. Their trial and error process ended with the horse’s success or failure, and the next injured horse had to be the subject of repeated trials somewhere down the road.

In 1859, George Dadd described using slings in a resigned tone that didn’t bode well for his patients in those pre-sedative years: “If horses when they are fresh should be placed in this machine, most of them would either injure themselves or break through all restraint. However, by tying up their heads for three or four nights, their spirit is destroyed. The slings may then be applied without fear of resistance…In this fashion a horse may remain for months in the slings.”

In the United States, veterinary hospitals and surgeons were few and far between until the late 20th century. A horse that might have benefited from being in a sling might not be in any condition to be moved to a hospital with a high-quality sling system, and if it could be moved, a considerable time would pass before the surgeon could work on the injured limb.

An example of a successful graduate of sling use for orthopedic use is the great racehorse, Kentucky Derby winner Swaps. The 1956 Horse of the Year hung from a sling at Garden State Racetrack in New Jersey after injuring his hind leg during training; after it was set, he broke the cast. Enter a sling. It took four veterinarians three hours to rig it and get the horse into it. His trainer was instructed to raise (or lower) the apparatus every 45 minutes in the horse’s best interest. He complied and did not leave the horse’s side for the first 36 hours. All questions about the horse were referred to his surgeon, Dr. Charles Raker of Penn Vet.

Six weeks later, the therapy was deemed a success and Swaps was off to a long and successful stud career. Oddly enough, the sling apparatus was loaned to Swaps’ trainer by “Sunny Jim” Fitzsimmons, trainer of Nashua, who had defeated Swaps in a match race.

Awareness and use of slings changed in the late 1900s, as equine surgery advanced out of the veterinary colleges and into referral hospitals that tended to be located close to the centers of horse breeding or competition. Equine ambulances were built to transport injured racehorses off the racetrack. More horses were insured, and owners had more reasons to want to give their horses a chance as the companion animal attitude toward horses blossomed.

At the same time, imaging and diagnostic equipment could evaluate the effectiveness of a sling compared to any ill effects, especially on a horse’s vital organs. A horse’s tolerance of a sling could be improved with the use of sedatives. Even with our advanced medications, some horses are claustrophobic in slings and careful case selection is critical. Vet students see slings routinely in use during their education; Penn Vet is famed for using a sling and a powerful hoist to move a horse from the operating theater to the college’s innovative anesthesia recovery pool.

The golden age of horse slings really began when Charlie Anderson and a group of veterinarians and students at the University of California at Davis experimented with Anderson’s plans for a complex, but effective, sling system. While the Anderson Sling was a game-changer for equine hospitals, the developers foresaw another critical use for it: the airlifting of horses from the bottom of ravines or other difficult-to-reach locations where horses are disabled.

The sight of a horse dangled from a harness in the sky under a helicopter guaranteed the new product plenty of publicity. At the same time, it implanted in the horseowning public a new hope for horses to be able to recover from severe injuries and neurological disorders.

What we know about slings is constantly being tested and improved from outside the horse world. The transport of zoo animals and marine mammals requires expert sling mechanics, and zoo curators must always evaluate the safety considerations of transporting an animal before agreeing to acquire it.

This third category of sling use is the field of large animal rescue, where the sling has taken many forms. Some have been sophisticated, some have been primitive; some have been brilliant solutions to difficult situations, and saved a horse’s life. The continuing education of emergency responders, usually through TLAER, has enabled them to strategically extricate a horse from a ditch, river, quicksand or snowbank (and many other situations). In the field, slings may be lifted by construction equipment or a tripod system, but trained responders understand how to support a horse before attempting to move it.

Rescue slings can be made of straps from old firehoses or be purpose-built rescue-intent systems like the Large Animal Lift that are designed to get straps around the horse for secure, safe lifting to safety. Cities and towns are learning the value of owning (or sharing) up-to-date equipment for large animal rescues, and working with veterinarians and horse owners to practice skills on model horses before the real situation calls them to action.

A final and critically important area for sling use is in the relatively new, but burgeoning, field of welfare-based non-profit horse rescue and compassionate care. Many rescue horses may be weak or affected by chronic diseases like Equine Cushings Disease that leave them in need of support. Rescue organizations may not be able to afford, or have a place for, a complex sling like the ones found in vet hospitals. They may improvise, but they may also move the entire field forward with their ingenious–and often successful–support systems and workarounds.

For individual owners, a safe sling can be an important piece of equipment. Horses with laminitis can especially benefit; they may not need to be in the sling all the time. Farriers especially appreciate working on a horse in a sling if it is properly restrained and quiet, since many lame horses find it very painful to put extra weight on an injured hoof while lifting the opposite one. Injured horses may ultimately show their appreciation by steadily improving until “hanging around” is something they no longer need to do.

We’re now in an era of great innovation and interest in the rehabilitation of horses, and the sling, in its many forms, is a central tool. The idea of a lame horse in a sling for the purpose of careful shoeing, medicating hooves, or changing boots and bandages at home brings the use of slings full circle from the earliest idea of a tool to help farriers safely shoe an ox or draft horse.

But the story doesn’t end there. Last week, the University of Saskatchewan shared news of an advanced sling support in use at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine there.

The Canadians are combining technology, clinical experience and equine biomechanics to help perfect the suspension capabilities of a hospital sling. Their unit is remote controlled, so that tension of different parts of the horse’s abdomen or chest can be alleviated. The system allows the animal to be mobile with its weight partially or fully supported by the lift.

While the unit has only been tested on healthy, uninjured horses so far, trials will help the team determine how the lift affects the horse’s behavior and basic physiological parameters, such as muscle enzyme levels and blood flow. They will also monitor the animals for pressure sores caused by the sling.

To review, three principle reasons to use a sling are:

- Active horse rescue from a ditch or in deep mud or snow; the University of California at Davis even utilizes a sling for air rescue of horses trapped at the bottom of canyons.

- Prolonged and variable weightbearing relief: Hospitalization of horses with severe orthopedic injuries in a critical care situation.

- Compassionate care of chronically sore or laminitic horses at home to provide temporary relief or ease in treatment without causing undue stress for the horse.

Slings have been the first line of assistance for hospitalized horses that need to get off their feet, but not be recumbent continually to achieve weightbearing relief. They also have a myriad of uses in layup situations or chronic nursing care on farms. They’re not perfect, and they won’t be the answer for every injured horse.

Building a better sling is still a challenge that inventive people tackle with the best intentions. But the challenge of Henry Ford, revived by Steve Jobs of Apple, comes to mind. He (allegedly) quipped that, when he invented the mass-produced motor car, he changed the paradigm by not asking the public to envision what they wanted their future transportation to be like: “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses,” he said. Instead, he gave them the future.

Can that train of thought be applied to slings? Are there other ways to get horses off their feet, or is it possible to create a support mechanism that is less bulky, easier to remove; one that doesn’t rub, cause sores and create stress? Is someone, somewhere designing a wearable sensor that will monitor pressure of a sling on different locations on the horse’s body? Perhaps the sling paradigm as we know it is as good as that mechanical concept is likely to get. Is there another way?

• • • • • •

Note: There’s no question that stocks and slings can be helpful to injured or unstable horses, but there are situations where they are not warranted, as well. Always consult with a veterinarian on the appropriateness of a sling for your horse, and how often you would use it. Slings can also hurt a horse and the people around it if used improperly, are attached to structures that can’t support their weight, or are used on an uncooperative horse. Horses in slings should not be left alone and the harness should be checked for rubbing and soreness at pressure points.

To learn more:

Carter, William H. Horses, Saddles and Bridles. Baltimore, Maryland: Lord Baltimore Press, 1906.

Full body support sling in horses. Part 1: equipment, case selection and application procedure

Ishihara A, Madigan JE, Hubert JD, McConnico RS

Equine Veterinary Education, 2006

Slings, bedding materials and stall design Donald M. Walsh Proceedings of 2007 International Equine Conference on Laminitis and Diseases of the Foot

Trimming and shoeing the recumbent horse Michael J. Wildenstein Proceedings of 2007 International Equine Conference on Laminitis and Diseases of the Foot