Are veterinarians risk-takers? When it comes to the risks they face on the job each day, statistics show that vets are more likely to be injured that any other professional. It is the riskiest of all jobs, and the injuries most often come in the form of a horse hoof making contact with a vet’s head, limbs or body. Ouch.

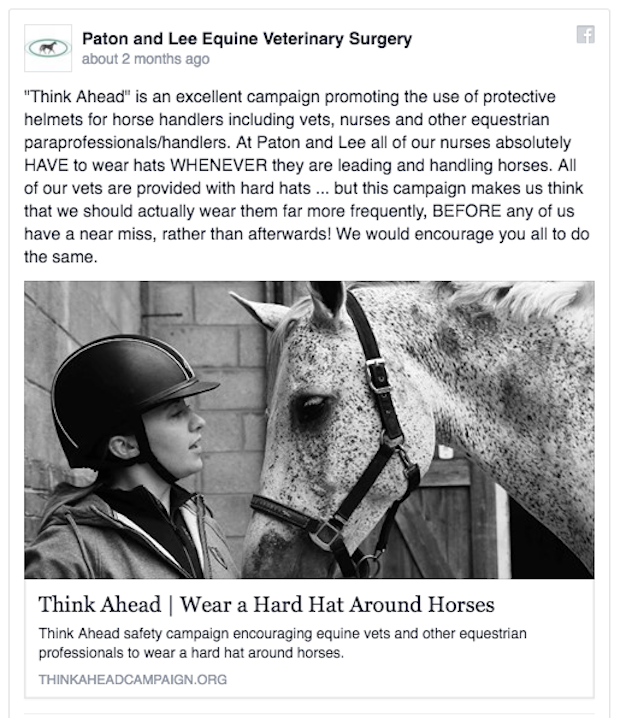

Why don’t vets wear helmets? That’s the question that British veterinarian Jill Butterworth, SEBC, PTC, BHSAI, BVetMed, MRCVS is asking. Her “Think Ahead” campaign is gaining attention, and starting conversations. A former riding instructor who went to vet school later in life, Butterworth said that she was surprised when she saw the risky situations veterinarians were in, without any protective gear on their side.

Butterworth makes her case this week in an essay on the pages of the British Veterinary Association’s Veterinary Record journal. Butterworth noted that Britain’s Society of Equine Behaviour Consultants is one of the few professional equestrian bodies to embed in their professional code of conduct that a helmet must be worn by the consultant and all helpers.

In 2005, writing to BEVA members, Professor Sidney Ricketts of Rossdale and Partners in Newmarket, England, recommended that veterinarians wear helmets and steel toe-capped boots during breeding operations. Some breeding operations now make vests and helmets mandatory for all staff during live cover and even collection procedures.

Others agree. Lisa Metcalf, MS, DVM, DACT of Honahlee, PC in Oregon spoke on breeding operations at the 2015 AAEP Resort Symposium. “Many injuries to breeding shed attendants and horse handlers can be readily prevented with appropriate attire,” she wrote in her proceedings paper. “Helmets should be a requirement. The most common helmets used are ASTM-certified riding helmets, but a motorcycle or hockey helmet with a face/mouth guard may yield superior protection.”

Butterworth’s case is compelling, and her campaign sticks to the message. She may or may not succeed in making any mandatory equipment policies, but her ability to raise awareness–for horse owners and employees as well as for veterinarians–makes her effort stand out.

“It is inconceivable to imagine fire fighters not donning their personal protective equipment, but a vet wearing a helmet is rare. Why?” That’s Butterworth’s central question.

Veterinarians may not be wearing protective gear in North America or in Great Britain, but things are changing for other horse professionals. Starting gate staff are now often outfitted in safety vests and helmets at racetracks, thanks to an Association of Racing Commissioners International model rule that has been adopted in many jurisdictions.

At colleges and vet schools, students handling horses from the ground may be required to wear helmets, and institutional grooms in the United Kingdom routinely wear them, as well.

What’s the reaction to Butterworth’s campaign?

A long list of statistics sheds light on the “how” part of veterinary injuries, but the “why” is not always obvious. While riders are injured in large numbers, people tending to horses from the ground tend to suffer more frequently from facial, head or abdominal injuries related to being kicked. As often as people fall off their horses and are injured, almost one in four injuries from horses affect unmounted people who are kicked.

Ten years ago in New York, an assistant starter was killed when he was kicked in the chest while loading a horse in the starting gate. Around the same time, a veterinarian died from head injuries suffered while working on a Morgan stallion.

The most recent tragedy was Irish veterinarian Gerry Long, who was kicked in the head by one of his client’s horses in 2014. His death was the impetus for the Think Ahead campaign.

It’s obvious that the veterinarian’s job is changing, and that work needs to be done to insure that vets are as safe as possible when working on horse properties and in their own clinics.

A report from the British Equine Veterinary Association (BEVA) in 2014 showed that the main cause of an injury to a veterinarian in that country “was a kick with a hind limb (49%), followed by a strike with a fore limb (11%), followed by a crush injury. Nearly a quarter of these reported injuries required hospital admission and notably, seven percent resulted in loss of consciousness.”

A 2009 study by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in the United States found that 48 percent of fatalities at US racetracks took place on the grounds of the racetrack, rather than during a race. Out of 17 people who died at racetracks, 14 were killed by horse kicks, and racetrack fatalities have increased since the 1990s.

On the other side of the fence, a report from Australia in 2015 was the first to survey injuries to veterinary and horse science students in Australia. Based on the frequency and types of injuries suffered by the students, the study’s authors, Christopher B. Riley, Jessica R. Liddiard, and Kirrilly Thompson stopped short of recommending protective headgear for students, but did suggest outfitting students in protective boots, gloves, and possibly padded coveralls.

Many veterinarians have been quoted as saying that wearing gear would slow them down in situations where agility is needed to get out of the way of a horse’s sudden moves; helmets might constrict peripheral vision or affect hearing a horse’s gut sounds or heartbeat. Helmet design is improving all the time, both in terms of the way that helmets fit the head and free the ears and eyes.

Additional criticism of helmets for vets centers on the fact that so many horse kicks hit people in the face, and that the skull is not the target. Psychologically, vets and technicians hesitate to wear helmets in case owners perceive them to be afraid of horses. One vet reported that her method for avoiding that perception was to request that owners or handlers also wear their helmets while she was working at a barn.

Researching this article revealed a deep and rich vein of research papers documenting work-related injuries to veterinarians. It begs the question whether Butterworth’s “Think Ahead” campaign is an idea whose time has come, or an idea that has credibility in 2016 because there is finally statistical evidence to back up her concerns.

What we don’t know is whether or not practicing veterinary medicine is more dangerous now that it was 100 years ago, 50 years ago, or even 20 years ago. Since the dawn of the 21st Century, numbers are available.

But how has the job changed? Are horses more dangerous than they once were? Are they less disciplined? Many veterinarians have a simple and clear policy of not working on horses known to be dangerous. Also, many make barn calls with veterinary technicians at their sides; one of their duties may be to hold a horse for the vet or assist with restraint, especially when an owner or barn employee doesn’t have the skills needed.

A survey by Elanco found that 93 percent of horse owners reported having had a horse sedated for a procedure such as shoeing, wound dressing or clipping. The advent of simple gel Detomidine can be administered by the owner instead of requiring an injection for shot-sensitive horses.

What can be done, and what needs to be done, however, is that horse owners and veterinarians should be communicating as allies in the cause of horse safety. Owners can design their facilities to provide safety-oriented places for veterinarians to work, or they may be encouraged to transport their horses to hospitals or a second location for treatment, when possible, rather than requiring veterinarians and technicians to work in unsafe situations.

At breeding farms, some sort of stocks or treatment trave can be commandeered for an unruly or young horse. Other horse owners might consider building a trave if they realized it would keep their horses and their vets safer during examinations or treatments.

Not so long ago, veterinarians were solo practitioners who knew all their clients and all the horses. They were aware of horses on their books that might be capable of misbehaving, although accidents often involve horses that normally would not be considered a risk. Today, when many vets are visiting barns on an off-hours or weekend “on call” basis or in a rotation with a staff of vets in a large practice, they can’t possibly know all the horses and their idiosyncrasies, or the danger spots in every barn.

Horse owners can keep arena use, barn aisle activity and feeding schedules in mind when booking appointment days and times for veterinarians to work on horses. Most of all, they can make sure that their horses are well-trained, sedated if that is the veterinarian’s preference, and not distracted by barn activity.

Many veterinarians accept the risks of their jobs, and know that horse owners may assume that their vets have superhuman powers when it comes to handling unruly horses. But like anyone, a vet can have a bad day, a sore shoulder, or the flu. Likewise, a normally bombproof horse can panic when its cast in its stall or suffering from colic pain or separated from pasture pals in order to be treated.

Jill Butterworth and her earnest Think Ahead campaign can make veterinarians and their staffs use their heads to re-evaluate risk as their practices and the horse world around them change. But what would a veterinary-specific helmet look like? Who would make it? And if a helmet was specifically created for veterinary tasks and protection, would vets buy–and wear–it?

When The Jurga Report asked Jill Butterworth about plans for a vet-specific helmet, her answer was disappointing.

“There is no veterinary specific helmet (yet),” she said, ” but other people have made the comment, so hopefully a commercial enterprise will help with this.”

This is one of those industrial design challenges that should be buoyed by a big cash prize. There’s a lot at stake, and no time to lose; Think Ahead needs all our help to get ahead.

To learn more:

Think ahead: safety first for equine vets

Jill Butterworth (2016)

Veterinary Record 2016;178:12 295-296 doi:10.1136/vr.i1355

Equine vets have the highest risk of all civilian professions.

British Equine Veterinary Association website news (2014)

Cross-Sectional Study of Horse-Related Injuries in Veterinary and Animal Science Students at an Australian University. Riley, C.B.; Liddiard, J.R.; Thompson, K. A Animals2015, 5, 951-964.

The Breeding Shed Metcalf, Lisa Proceedings of the 2015 AAEP Resort Symposium