The Way We Were: New York’s Extravaganza 1914 Horse Show Aided World War I Victims

- March 10, 2017

- ⎯ Fran Jurga

Cornelius Vanderbilt bought Rosa Bonheur’s massive painting, The Horse Fair, in 1887. It became one of the most popular paintings in American history and the public flocked to New York to stare at the eight-foot canvas in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. So the Red Cross Horse Show staged an arena re-creation of the painting for its fundraising horse show.

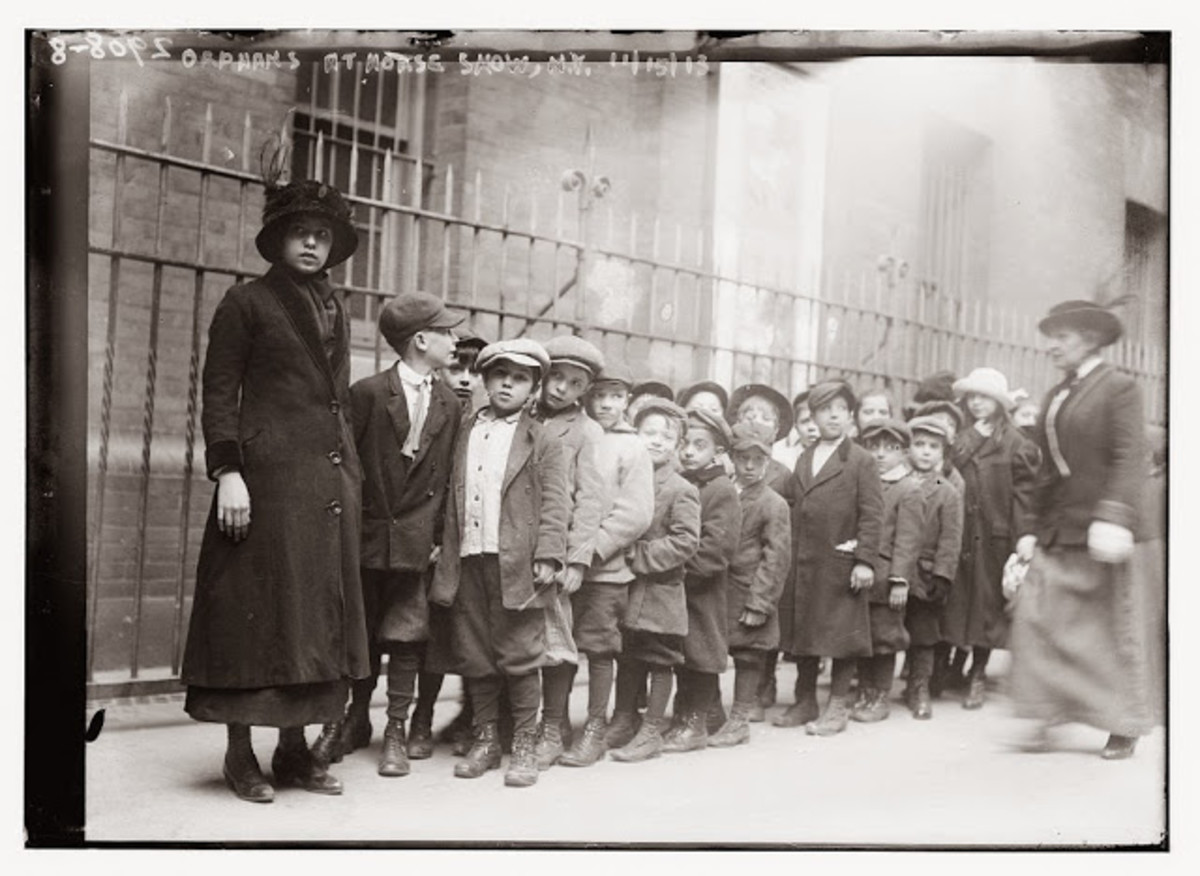

One hundred years ago, the National Horse Show was the social event of the season in New York City. Or it would have been, had it not been cancelled in 1914.

When the Red Cross stepped in and announced replacement plans for its own horse-themed fundraising extravaganza to support relief efforts in Europe, New York’s creative energy went into overdrive. Art, theater, popular culture and even the Wild West were recruited–or volunteered–in the name of charity.

Horse show planners of today could take a lesson from how they masterminded this event 100 years ago.

Were people bored with traditional horse shows or was the Red Cross simply eager to take theirs over the top? It’s hard to tell. Perhaps they hired the 1914 equivalent of Andrew Lloyd Weber to mastermind the show. Whoever pulled together the program seemed to understand that horses and New York artistic talent would make arena magic.

In October 2014, when the new Central Park Horse Show brought jumpers back to mid-town Manhattan, it might have been paired with an endurance race. The plans are still on paper somewhere, surely, since the Red Cross show of 1914 plotted a route from Squadron A’s cavalry stables in the 1,100-acre Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx through Central Park and down Fifth Avenue. After 14 miles, horses and riders ended the race dramatically at a finish line inside the Madison Square Garden horse show arena. Patrons were comfortably seated, protected from the December chill, but did not miss any of the excitement of the finish.

The race was limited to military or militia horses, and featured an inspection of the horses at the start by veterans of the Civil War, who would “eliminate from the race any horse that is not in evident condition and stamina for the contest,” an announcement in the New York Times read.

That was about it, for rules, but even those rules attracted attention and debate.

Five months later, the Brooklyn Horse Show built on the Red Cross race’s success by staging another military-only endurance race, this time at a distance of 15 miles, over the bridle paths of Brooklyn. An article in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle noted that the organizers felt that the condition of the horse at the finish was as important as at the start. The Brooklyn ride was the first that required a horse to not only have the fastest time, but to meet the conditions laid down for the race when it was over.

(Read more about the historic Brooklyn military endurance race of 1915.

The Red Cross show featured an exhibition of the city’s own hansom cabs and trade vehicles. including horse-drawn hearses, coursing the arena. This was billed as “a muster in the ring of the most picturesque sort of trade vehicle left to Manhattan. The ring will see a muster of hansom cabs, termed by Robert Louis Stevenson the ‘gondolas of the pavements’ and the array will be a notable one.”

Not to be outdone, another evening was devoted to coaching. “On the Road” filled the arena with coaches, horses and passengers in period dress and decoration, with a concert of coaching horn airs.

Should the parade of delivery and cab horses be too calm, the organizers had representatives on hand from the Mounted Traffic Squad. While they were surely there for safety, show publicity suggested that they might be called on to demonstrate their skill at stopping at runaway horses.

Even 100 years ago, New York was the art capital of the Americas, and the most popular painting of the time was also the largest animal painting ever created. Rosa Bonheur’s “The Horse Fair” was painted in Paris, but Cornelius Vanderbilt gave it a home in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. To please the public, the Red Cross Horse Show recreated the painting in the arena, as a tableau vivant in motion.

Do you think that a New York rider was found who could control two mighty Percherons with single thin reins, as in this detail from the painting, courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art?

Music would not be left out. Music of the anvils, that is. How many horseshoers or farriers do you think were plying their trade in New York in 1914? The horseshoers union built forges in the arena and presented seven farriers and their helpers, all dressed in red shirts and black trousers.

The magic of music was to have been provided by operatic choruses from the city who would sing a selection of works paired to the clang of the hammers on anvils, as the horseshoers set to work shoeing horses as a demonstration for the audience.

Of course, Verdi’s “Anvil Chorus” was on the play list, although it had to be performed by the show orchestra in the absence of the opera stars.

According to the New York Times of December 10, 1914, “…the performance was a complete novelty and judging from the applause was the hit of the evening.”

Finally, there was “Cheyenne Day”, with cowboys and cowgirls galore, complete with wild horses. Ticket holders could expect “rough riding, bronco breaking, and lassoing”.

From the opposite end of the spectrum, French rider Emile Antony demonstrated the movements of the haute ecole on his stallion

Masterpiece. He rode in the saddle of his grandfather, who had ridden in that saddle in Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow. There’s no mention of the word “dressage”.

In another way, 100 years seems not to have passed at all; Mrs Harry La Montagne’s newly-purchased off-track Thoroughbred (ex-racehorse) Northman tasted victory in the Thoroughbred saddle class. But just as convincing a reminder that time has passed is that there was a class for the local and visiting cavalry horses: “Officers’ Chargers Up To Carrying 210 Pounds”. There was also a class for polo ponies.

Still not impressed? The entire troop of the 10th Cavalry was deployed to Manhattan to be part of the horse show, under a direct order from the Secretary of War issued December 2, 1914. Their orders directed them to serve as guard and escort throughout the show, and to parade twice a day through Manhattan from their quarters to Madison Square Garden.

All this was in addition to 1,200 jumping, riding and driving horses entered in the competitions, which included the first full classification of five-gaited horses. The handicap broad jump class had 52 entries.

Theater, art, and music at the horse show…could the interior decorators be far behind? The decision was made to tone down any festive decor, in light of the serious mission of the show. Red and white draping filled the building, with festoons from the boxes to the floor of the promenade, with overlays of the Red Cross symbol.

The ceiling girders were cover with a cloth canopy; the chandelier was left to it own grandeur. Madison Square Garden was transformed and transcended. The Red Cross had both a fundraising stage and a dignified platform to share its call for humanitarian action in Europe.

The show had everything going for it, except the weather. Newspaper accounts tell of rain and snow affecting the grandeur of the evening wear–and attendance.

An important “first” debuted with this unique 1914 horse show, and that was the opening of the stables under Madison Square Garden to the public, so that the public could “meet the horses”.

Research for this article showed that horses were big news at the time when this extravagant horse show was announced and when it was on. Daily reports in newspapers kept tallies of the number of horses and mules–usually 1,500 to 2,000 a week–that were being shipped overseas to assist in the war effort.

Even though the US was in a love affair with automobiles, there was still a widely-held belief that horses were needed here and that they would be especially needed if the United States entered the war. Some worried that a shortage of horses might even prevent the US from entering the war, when and if it was capable of undertaking that giant step.

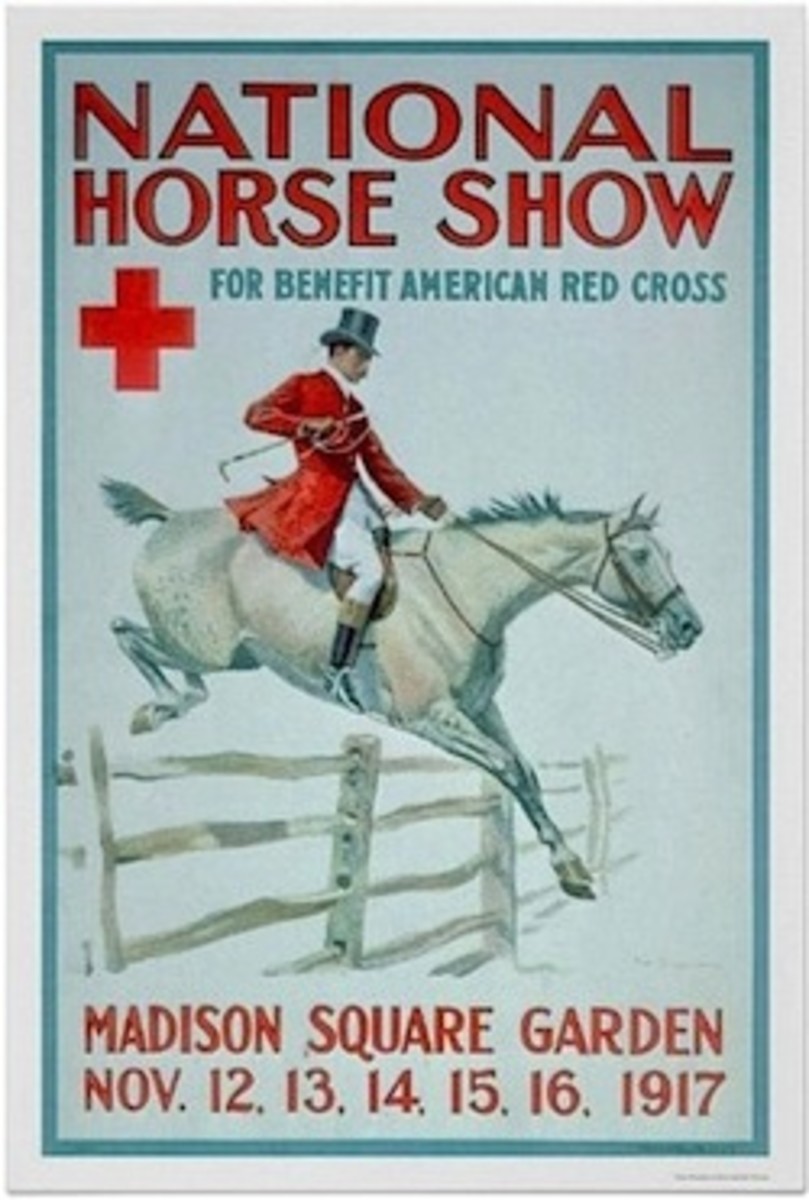

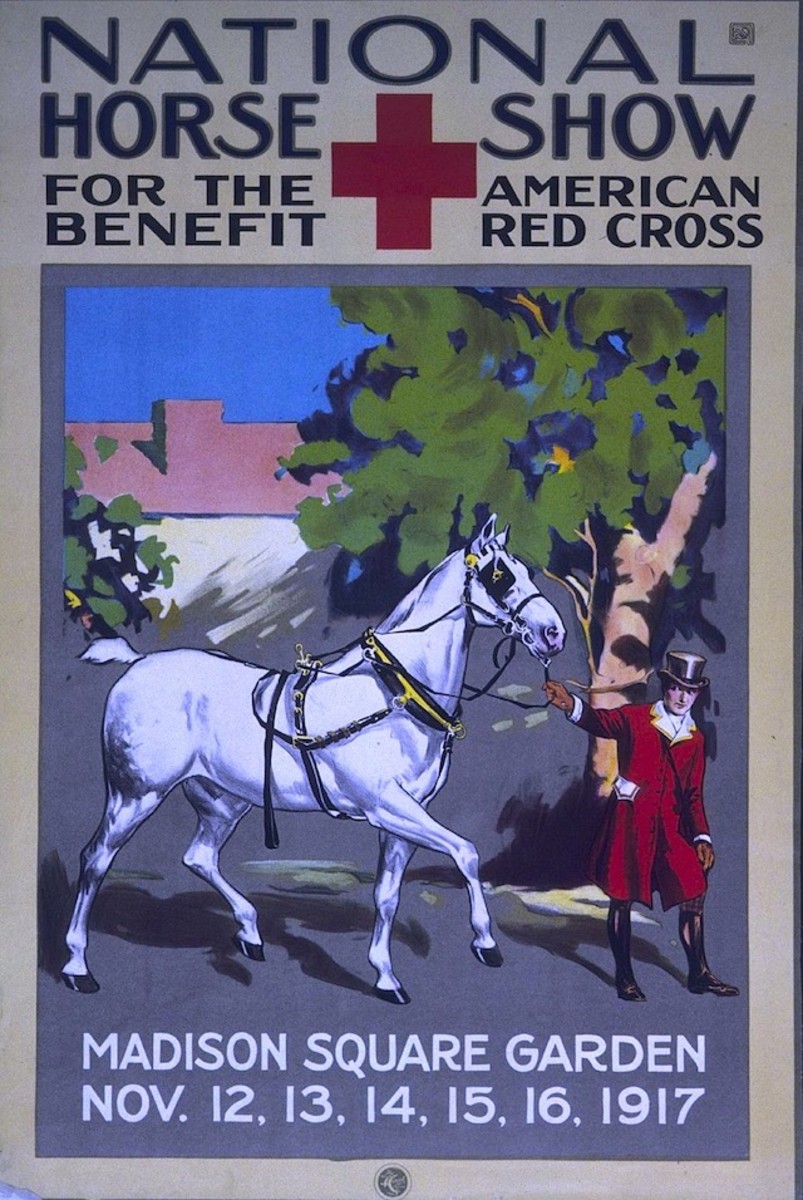

By the time the United States officially entered the war in 1917, the National Horse Show was back in action, under the stewardship of the fledgling American Horse Shows Association but it should be noted that the Red Cross was the show beneficiary–and remained in that role for many years.

Research in the archives of the New York Times and horse show magazines of the day made this article possible.