Blinkers Off! Horses, Heat and Heavy Bridles Stirred Emotions Long Ago

- March 10, 2017

- ⎯ Fran Jurga

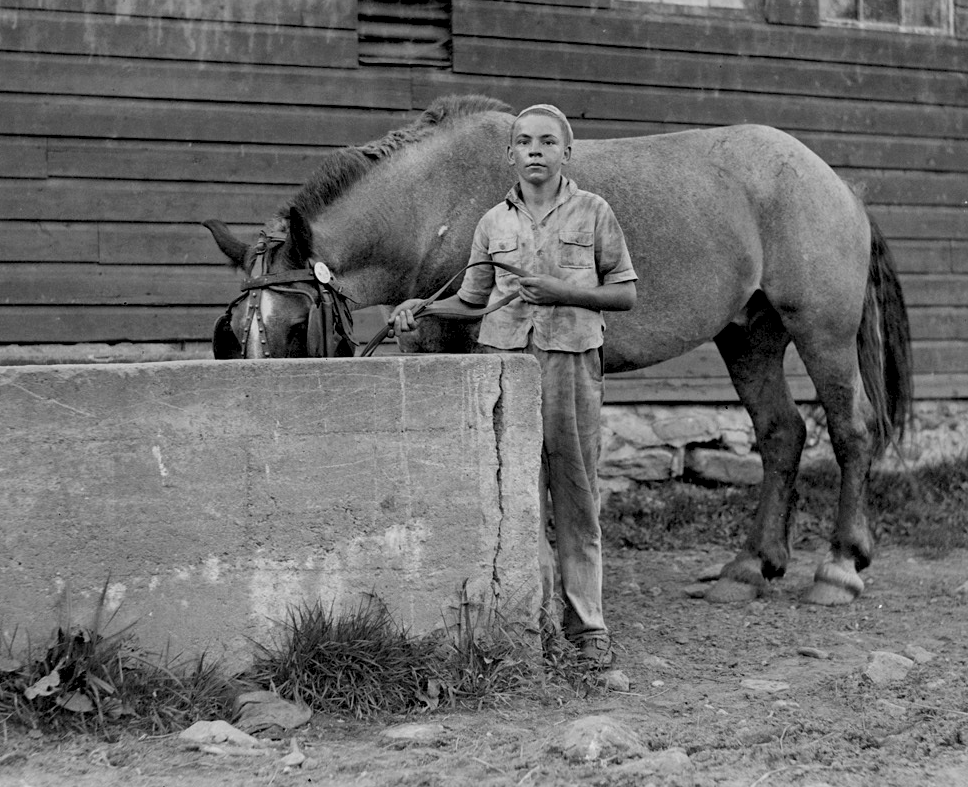

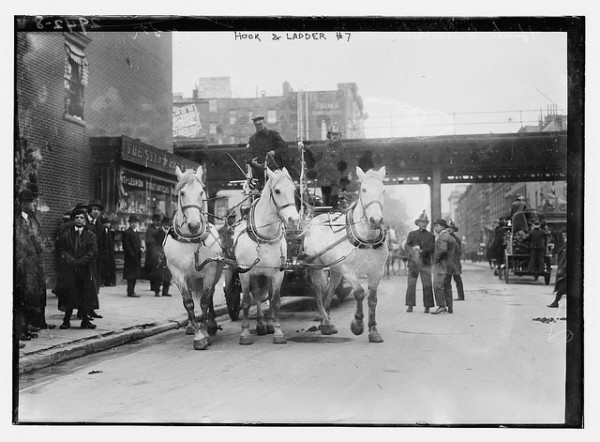

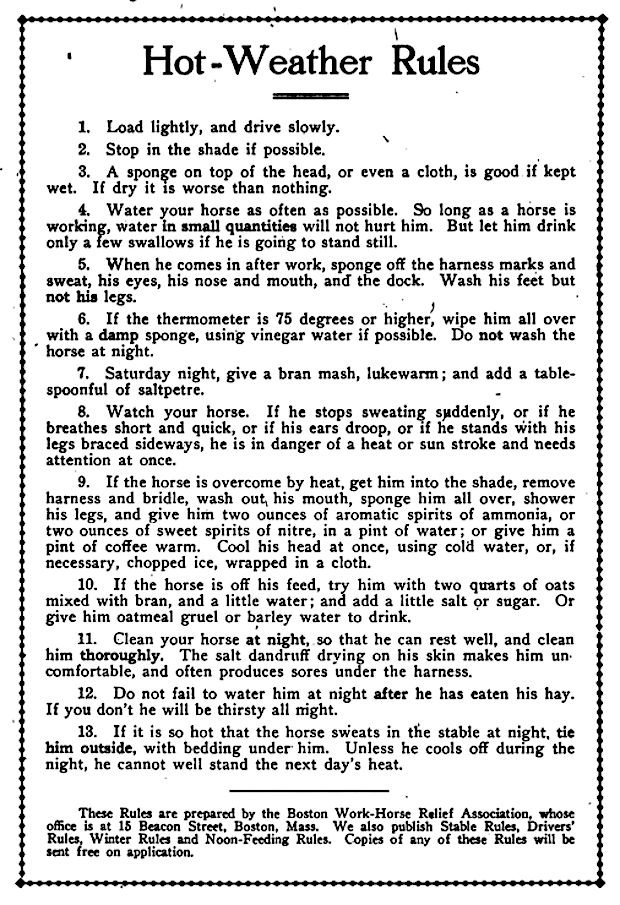

Horses on city streets 100 years ago had hard work to do. They pulled heavy loads, worked long hours, and probably couldn’t remember what a field looked like or fresh grass tasted like. When the thermometer plummeted in winter, turning the streets to ice, or skyrocketed in the summer, melting the very pavement beneath their hooves, they worked not just against the loads they pulled and the traffic they maneuvered but the elements around them.

Their plight was not ignored, however. In cities around the world, big-hearted people and clever people joined forces to see what could be done to keep the horses on the job, but more comfortable. In the winter, that meant blankets and non-skid boots and shoes. In the summer, that meant water fountains, certainly. Washington, DC had 153 drinking fountain for horses. But the humane societies didn’t stop there.

This month, the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (MSPCA) is celebrating the 100th anniversary of the opening of the Angell Animal Medical Center, known around the world by its old name of “Angell Memorial” Animal Hospital. The MSPCA was one of the leaders in helping horses on the street, as explained on The Jurga Report five years ago with photos of horse watering stations in Boston and other cities.

Water was critical, but reformers didn’t stop there. Work horses wore large, heavy bridles on their heads with wide, thick cheekstraps and blinders. Activists turned to saddlers to invent a lighter summer-weight bridle, with thinner straps, which the ASPCA gave away in New York.

It was no secret that the humane groups hated check reins–the bane of Black Beauty’s existence when he was a cab horse, and so eloquently described in that book–but they went even further and asked drivers to remove the blinders, because they felt they weighed too much. Removing them would allow for light, thin straps on the horse’s head since they thought the true contact with the bit was through the reins, not the head stall or noseband.

While the New Yorkers gave away entire bridles, the thriftier Bostonians of the MSPCA had lighter weight blinderless cheekpieces made for work horse bridles, and gave those away. That way, the blinders could be swapped in or out. Each piece had a buckle at the top and a snap at the bottom for the bit; a brass plate advertised that it was approved by the MSPCA.

Whoa…(literally). Horses in the city are prey animals at their most vulnerable. Trucks come up behind them. People come at them from every direction. The blinders seem like they are a humane attachment to the harness, one that prevents the horse from fearful reactions and elevated adrenalin. Horses were trained to drive with blinders. What would happen if you took them off?

The MSPCA was methodical in its work. In one three-day period in 1912, they counted 10,003 horses going through their watering stations in Boston. Of these, 9,822 had blinders on.

“We readily grant that now and then a horse is found that may drive better with them than without them, but that is the exception,” wrote the group’s president, veterinarian Francis H. Rowley in “Our Dumb Animals”, the MSPCA magazine. “That the ordinary teaming horse should be subjected to this device is nothing less than the result of somebody’s stupidity.”

Today, driving and draft horses routinely wear blinders. Where we don’t see them in New England is in pulling contests, so the horses can see the teamster drop the chain, presumably, and out west, in some (but not all) rodeo chuckwagon and chariot teams like the Calgary Stampede.

The activists distributed fly nets, too.

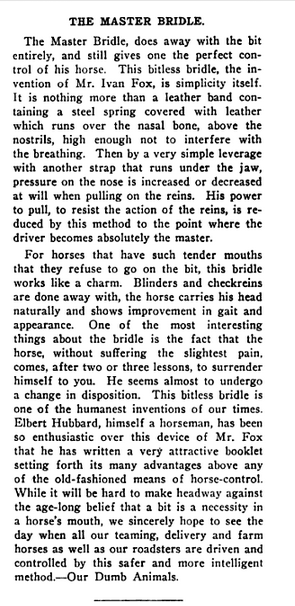

The final innovation that the humane reformers felt would help work horses beat the heat was to remove the heavy bits that they carried in their mouths. In 1912, they touted an invention by Mr. Ivan Fox called the Master Bridle. From the description, it sounds like a cavesson with a leather-covered spring embedded in it. The spring ran over the nasal boned and received leverage from a strap that ran under the jaw.

Rowley wrote optimistically, “While it will be hard to make headway against the age-long belief that a bit is a necessity in a horse’s mouth, we sincerely hope to see the day when all our teaming, delivery and farm horses as well as our roadsters are driven and controlled by this safer and more intelligent method.”

Photos of Mr. Fox’s invention eluded all searches.

Things were bad for horses in the city during heat waves, but they were dangerous for all animals. In New York, temporary shelters were built in city parks in the summer of 1921 so that dogs and cats and any other animals that were starving or sick or struggling to survive in the heat could be euthanized.

This story should end here, but once the MSPCA conquered the bridle issue, they went on to stop the docking of tails–with a vengeance, no doubt fueled by the success of their summer heat campaign. We have to wonder why blinders are still worn, if the MSPCA, ASPCA and other humane organizations removed them from the city horses without any repercussions. But perhaps “the rest of the story” is buried in the library, yet to be discovered, or a reader will tell us what happened next.

P.S. Be sure to read Horses and Heat Waves: How Did City Horses Fare in the Old Days? from five years ago on The Jurga Report.