Words can hurt. In an age when we toe the line to protect equine welfare, what are we doing to protect each other?

Are horses–and the future of the entire equine industry–at risk?

• • • • •

When a British boarding stable launched the #notonmyyard social media campaign last fall, the world didn’t stop to take much notice. Perhaps they didn’t know what it meant.

When the world governing body of horse sports, the Federation Equestrian Internationale (FEI), endorsed the hashtag and featured the campaign on its website, no one seemed to take much notice, either.

The unusual campaign exposes something we really don’t want to talk about: bullying in the horse world. Launched by Tudor Rose Equine in England, #notonmyyard urges trainers and stable owners to take a stand against harassment by adopting a policy of zero tolerance for bullying of anyone, by anyone.

We all know that bullying exists, we all see it, and we all claim to abhor it. But controlling bullying is like not cleaning your tack because it looks like it’s clean. The dirt and dust and potential mold are there. If you don’t clean it, you may smell an unpleasant odor the next time you want to ride.

Most of the time, we just dismiss bullying, make mental notes of who the mean people are, and move on. We think it will go away. The children will grow out of it. The “barn witch” will move to a new place. We’ll never take a lesson with that trainer again, or hire that farrier a second time.

Two stories in the news recently point to a different way of thinking about bullying. But instead of being about weak and helpless victims, the victims are athletes at the zeniths of their careers.

We’re all aware of cyberbullying, whether we’ve seen it on Twitter or Facebook or those horrid mean comments left on YouTube videos and in forums. Anonymity emboldens people. There’s no one for the victim to confront. Welcome to the Internet.

What is bullying? According to The Pony Club, bullying is defined as “deliberate hurtful behavior by an adult or child, usually repetitive behavior, which may result in pain or distress to the victim. It can take different forms including emotional, physical, racist, verbal, sexual or online bullying”. In organizational behavior terms, particularly among adolescents, bullying is termed “relational aggression”.

Just ask Olympic gold medalist Gabby Douglas. Critics of her subdued award ceremony behavior on television at the Rio 2016 Olympics gave rise to an especially vicious social media hate campaign that targeted Douglas at the moment when she should have been at her highest.

Last month, Douglas came forward, told her story on national television, and announced that she would work as a spokesperson for a social media campaign called #HackHarassment. She’s standing up for herself, and for everyone who’s been the victim of haters online.

This story might end here except that, a few days after Douglas’s story broke, it took an equestrian twist.

On New Year’s Eve, the horse world stopped in its tracks when it read a British newspaper interview with Irish equestrian Susan Oakes. Oakes holds the world record for sidesaddle puissance and triple bar jumping. She, like Gabby Douglas, is at the top of her game, but she has been at the bottom of her self-esteem and even contemplated suicide.

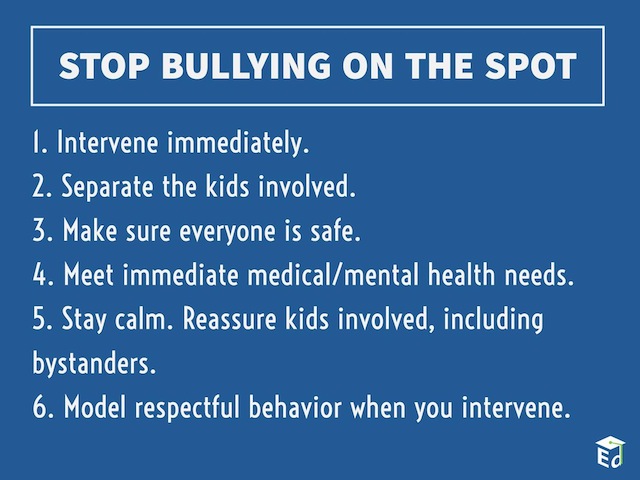

Bullying advice from StopBullying.gov.

The picture that Oakes paints of equestrian sports is of a world so corrupted by bullying that harassment is compromising participation in sports, or even the decision of some people to own horses or take lessons at all. According to Samantha Thurlow, founder of #notonmyyard, about five people a week come forward to tell their experiences, and how many came to leave equestrianism because of the way they were treated by others. Oakes was one of them.

In Susan Oakes’ case, she was harassed by horse dealers. She said in her interview with The Telegraph, “I went down some roads so dark that I didn’t think there would be a tomorrow. At night, I actually prayed that I wouldn’t wake up the next morning.”

“I have seen people hospitalized for depression caused by stable bullies,” she continued. “This campaign – Not On My Yard – can really make a difference. If people feel protected and empowered to speak up, it will help immensely.”

According to Thurlow and Oakes, people who are bullied change their routines to avoid harassers. They ride at odd hours. They don’t go to certain shows. They might move a horse to a stall at the other end of the stable. They start investing in more padlocks for their tack trunks. They think about where they park their cars. Most alarmingly, they fear for their horses; they lock up medications, feed and supplements, and scrub buckets extra clean. They check their tack straps and stirrup leathers. They start to show up to take their horses out for paddock time themselves. They stop trusting.

They start to wonder if their harassers know where they live.

While most say that their reputations were damaged, or even ruined, by their attackers, it can be much worse than rumors. The ultimate fear for a horse owner is always wondering if your horse is safe and if you can trust the people with access to his stable or paddock. People gave examples of horses that had had their tails or manes cut. Gates that were left open. Trailers that were vandalized.

The campaign has been endorsed by horse world icons like Monty Roberts and Kelly Marks, dressage judge Stephen Clarke, and British showjumper Geoff Billington.

Great Britain doesn’t have a corner on the market for equestrian bullying awareness. Websites in Canada and Australia also focus on equestrian bullying.

In the United States, we have countless examples of harassment, including intimidation of horse show judges and stewards during competition, and even pressure on horse show organizers over the selection of the judges.

Going horse shopping must have been the origin of the expression “buyer beware”; potential buyers quickly learn that it is more important to know even more about the seller and/or agent, than about the horse itself.

What we don’t have yet is a global campaign to promote what we should take for granted: a culture of fairness and respect for each other. It seems so obvious. It is the picture that all breed and sport associations paint, but who’s working to make sure that it’s a reality for the people who are potential lifelong competitors and owners?

If we lose them, we have lost our future.

Of course, it is easy to say that the world is a less friendly place these days, and that equestrianism simply reflects that. It’s also easy to say that it’s a tough world out there, and both children and adults need to learn to stand up to bullies, face adversity and “get on with their lives”. And doesn’t the love they receive from the horse make up for the pain?

When we hear of the equine studies major in Arizona who committed suicide after harsh criticism from instructors, or the farrier apprentice in England who ended his life, we know the answer. When we look at the comments on young riders’ YouTube videos, we know the answer. When we see vilification of riders on Facebook, we know the answer.

The answer is to get involved, to stand up, and to be a friend or mentor to someone who may need your support. The answer is for trainers and stable owners to create a culture of helping others and of inclusion, even while teaching competition and improvement of skills. The answer is to intervene on social media when someone is being verbally beaten up.

Bullying, especially by young girls, is an intense and complex behavior that may not be easily resolved. Some say that drawing attention to it either makes it worse or drives it into secret behavior instead of in the open. But it can be excluded from places where animals live and work, and where the safety of boarders and students and spectators is at risk. Horse activities and even shows can be adjusted to have more team-building activities.

Owning a horse should be a joy that you can share with others. It shouldn’t be about fear or embarrassment or dread or self-loathing. Please do what you can in 2017 to work with organizations and businesses to build awareness of bullying and to promote a more inclusive equestrian landscape where bullying is not tolerated.

To learn more:

Tudor Rose Equine’s #NotOnMyYard anti-bullying campaign Facebook page

Gabby Douglas story in the Washington Post

Susan Oakes’ world record puissance jumping video

FEI feature on #notonmyyard campaign

Arizona: Professors’ bullying led to daughter’s suicide

Also check weblinks to equine-assisted therapy and social work programs that use team-approach exercises, with and without horses, to de-fuse bullying. An interesting document is a teacher education essay, “It’s Not Just Girls Being Girls: Relational Aggression at the New Hampshire Equestrian Academy Charter School” by Casey Robinson.

Top photo: Roger H. Goun