Stress Response to Classical Extension vs Hyperflexed Neck Positions Compared in European Research

- March 10, 2017

- ⎯ Fran Jurga

The best position of the horse’s head has been extensively debated without any scientific evidence ruling in favor of either of the two main schools: should the neck be fully extended forwards and downwards or should it be “hyperflexed” such that the head almost comes into contact with the chest?

The research team of Professor Christine Aurich at the University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna recently compared the levels of stress on horses trained by each of the two methods and has found surprisingly little difference in the results. Her findings will shortly be published in the Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition.

Arguments over how best to train horses have raged for centuries. Two years ago, the International Equestrian Federation (FEI) was even moved to ban the practice of hyperflexion as a result of a petition signed by over 40,000 people who claimed that it caused the animals unnecessary discomfort. The FEI did make a distinction between hyperflexion by the use of extreme force and what it termed “low, deep and round” (LDR), which essentially achieves the same position without force.

How forceful hyperflexion should be distinguished from permissible LDR training was not clearly stated. Instead, a working group has been established to come up with an acceptable definition.

The debate between the proponents and the opponents of hyperflexion has given rise to considerable emotions on both sides but has unfortunately been limited by a lack of scientific evidence. Lead author Mareike Becker-Birck, a member of the Aurich team, has attempted to fill the void by comparing the levels of stress shown by horses trained on the lunge with their necks either extended forwards or fixed in hyperflexion.

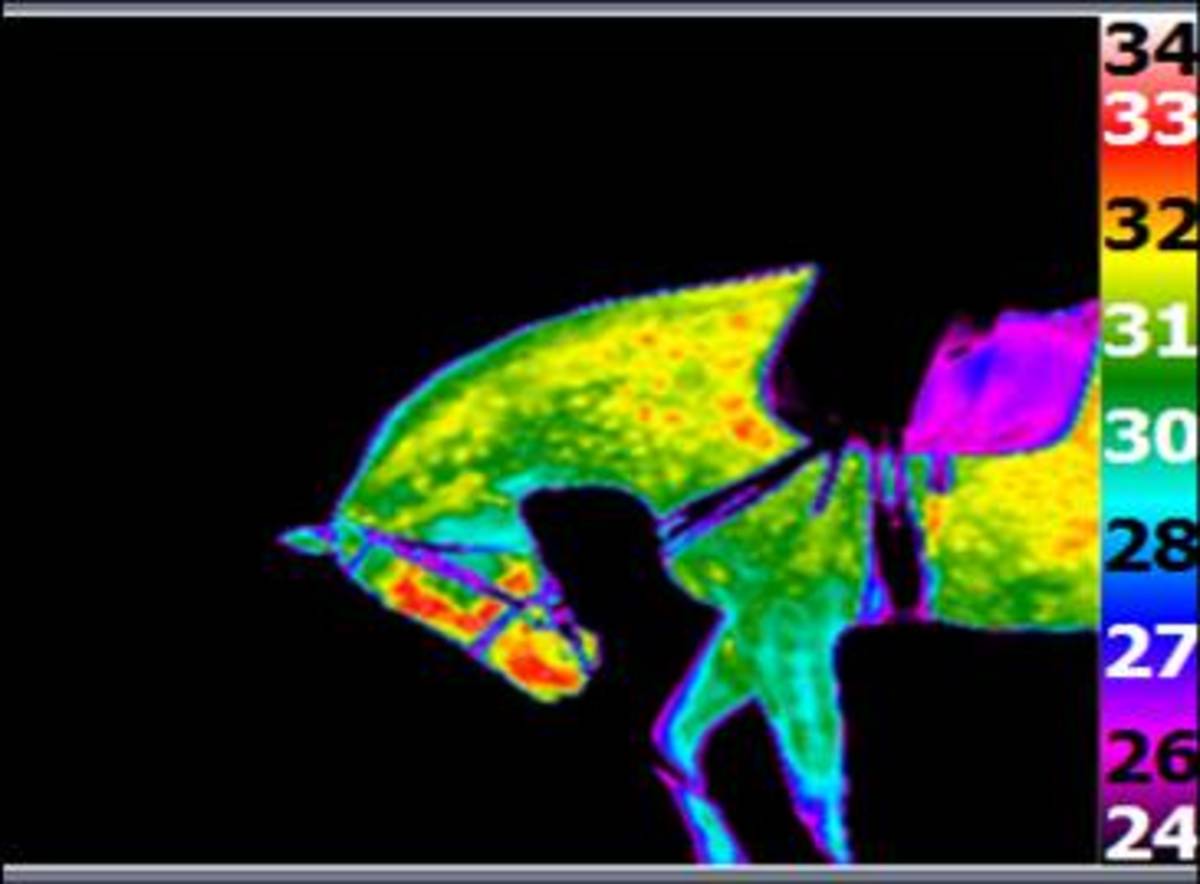

Stress was assessed by monitoring the levels of stress-related hormones in the animals’ saliva and by following the fluctuations in heart rate exhibited before, during and after training. In addition, the surface body temperature was measured before and after the experiment. None of the horses suffered any obvious discomfort during the training, which was undertaken without the use of a whip.

The horses showed an increase in stress hormones in their saliva, an increase in heart rate and a decrease in heart rate variability when they were trained. The changes presumably stem from a combination of physical activity and the normal stress responses. The level of stress incurred by the animals was not particularly high – the change in hormones in the saliva was actually less than when horses are transported by road or ridden for the first time.

And, importantly, the effects were the same irrespective of whether the animals were lunged under hyperflexion or under “classical” conditions with their necks extended. The only significant difference observed related to the temperature of the front (cranial) part of the animals’ necks, possibly indicating that the blood flow was not quite even when the horses were lunged in hyperflexion.

Apart from this one minor difference, the results show that hyperflexion in horses lunged at moderate speed and not touched with the whip did not elicit a pronounced stress response. In other words, the Vienna team writes, there appears to be no scientific reason to ban the use of hyperflexion.

Aurich nevertheless remains cautious. “Our results show that hyperflexion does not itself harm the animals but some trainers combine it with forceful and aggressive intervention by the rider over prolonged periods of time. This is a different situation from the one we investigated, so our study should not be interpreted to mean that hyperflexion never has any stressful or negative effects.”

The paper Cortisol release, heart rate and heart rate variability, and superficial body temperature, in horses lunged either with hyperflexion of the neck or with an extended head and neck position by Mareike Becker-Birck, Alice Schmidt, Manuela Wulf, J?rg Aurich, Armgard von der Wense, Erich M?stl, Reinhold Berz and Christine Aurich is published in the current issue of the Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition. The work was carried out at the Graf Lehndorff Institute for Equine Science, a joint research unit of the University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna, Austria, and the Brandenburg State Stud at Neustadt (Dosse), Germany.

To learn more:

The Nose Knows: Equitation Scientists Call for Monitoring of Dressage Nosebands at Competitions

FEI Schooling Head and Neck Positions, Body Frames Clarified with Illustrations

FEI Rollkur Roundtable Resolution: Aggressive force unacceptable, LDR still acceptable

Thanks to the University of Vienna for material provided for this article.