Latest Study on Potential Ecological Impact of Horses on Trails Is a Call to Action for All Horsemen

- March 10, 2017

- ⎯ Fran Jurga

Half a world away, Australian researchers are making a list of reasons why you shouldn’t be riding your horse on public land this weekend. Is the horse a natural part of public land or its enemy?

Most equine research is done by people with a connection to equine science or veterinary medicine. They may have a built-in bias toward the horse. But every once in a while, studies are published by scientists with no ties to horses.

A study in a scientific journal hovers over some aspect of horses that sounds foreign to those of us within the horse industry. Taking the sport, work and companionship angles out of the equine equation can be a wake-up call.?That’s how we felt in the past about European studies on horse meat, or American endocrinology studies of hormone therapy medication for women derived from the urine of pregnant mares.

Today, a new study looks at horses as weed seed distributors rather than a recreational companion, sport participant or pet. And if you were an ecologist, you might think of them by what’s in their manure, too.

A group of researchers at Australia’s Griffith University, led by Associate Professor Catherine Pickering, looked at the number and types of weed seeds that have been found dispersed through horse manure in national parks around the world. The findings have been published in the journal Ecological Management and Restoration.

“We reviewed 15 studies on seed germination from horse dung; six from Europe, four from North America, three from Australia and one study each from Africa and Central America,” Associate Professor Pickering said.

“Of the 2739 non-native plants that are naturalized in Australia, 156 have been shown to germinate in horse dung,” she continued. “What is very concerning is this includes 16 of the 429 listed noxious weeds in Australia and two weeds of national significance.”

The study found a similar threat is emerging in other parts of the world, with seeds from 105 of the 1596 invasive/noxious plant species here in North America also germinating in horse dung.

“Not only are the seeds dispersed through dung but the manure provides the means by which the introduced plant take hold,” Pickering said.

“Habitat disturbance from trampling has been demonstrated to further facilitate the germination of seedlings from dung in both natural and experimental studies.”

The study highlights the range of plant species which have the potential to be dispersed over long distances but the extent to which this dispersal is harmful depends on the individual plant species.

Some plants germinate from dung and go on to reach maturity and flower, while others germinate but don’t survive.

But there are other factors to consider.

“Additional threats come in the form of trampled soils and vegetation, nutrient addition via dung and urine, and changing hydrology via damage to riverine systems,” Associate Professor Pickering said.

“To maintain the conservation value of protected areas, it is vitally important to understand and manage the different potential weed dispersal vectors, including horses.

“Legislators everywhere should take these into consideration before opening parks to this recreational activity,” she concluded.

If you think that Dr. Pickering is picking on horses, think again: she published a paper last year that cast humans as the guilty party. Seeds can cling to the socks and pant legs of hikers, creating a risky situation for the spread of black spear grass in Australia’s Kakadu National Park. In a 2009 paper, she compared the impact of horses with hikers and mountain bikers.

This type of research falls under the heading of “sustainable tourism”. You might not have had much impact from this where you live, but here in New England, equestrians were shocked to learn that their access to Department of Resources and Economic Development (“DRED”) beaches and trails in New Hampshire is threatened by new laws, which may require riders to dismount to gather manure.

We’re accustomed to seeing “diaper bags” hanging under the tails of city horses; will we see them on the trail in the wilderness one day, too?

A document provided by the New Hampshire Division of Parks and Recreation revealed that none of the other New England states or New York have laws that require or request manure cleanup, other than around camping or parking areas.

Back Country Horsemen of America is an organization dedicated to preserving horseback access to public lands in the United States, and they have countered what they call the “myth” of seed spreading via manure. However, with each new study published, the task becomes potentially more difficult.

The Nature Conservancy published a summary of ecological impacts on trails in 2000, which includes many ways that horses affect trails and the adjacent land. Groups like American Trails are excellent sources of ongoing information; American Trails has an extensive resource library for anyone wishing to know more about horse access to trails.

As we lose public land closer to urban areas and trail access is lost, pressure to comply with conservation restrictions on existing trails and state or national parks is sure to increase, as seen in New Hampshire this fall.

Studies will be needed to determine the impact of increased equine traffic on trails, but it will also be up to horse owners to be pro-active about equestrian access to trails, and to support trail and outdoor organizations that are horse-friendly.

Trail maintenance and restoration will become ever more critical issues, as opponents of horse use of trails will be counting hoofprints in the earth and bringing up studies like potential impacts of E. coli from manure on water runoff or the spread of weed seeds.

How will we defend horse use of public land? What if those Idaho horsemen hadn’t been out on the trail when the kidnapped California girl was spotted last summer? They probably saved her life. What if horsemen weren’t available to search for lost hikers or plane crash victims? Riders notice things, even when they aren’t looking for something: a gate left open, a car left in a parking lot overnight. Horses and riders are valuable in many ways to the back country and even to suburban conservation land and trails on private land.

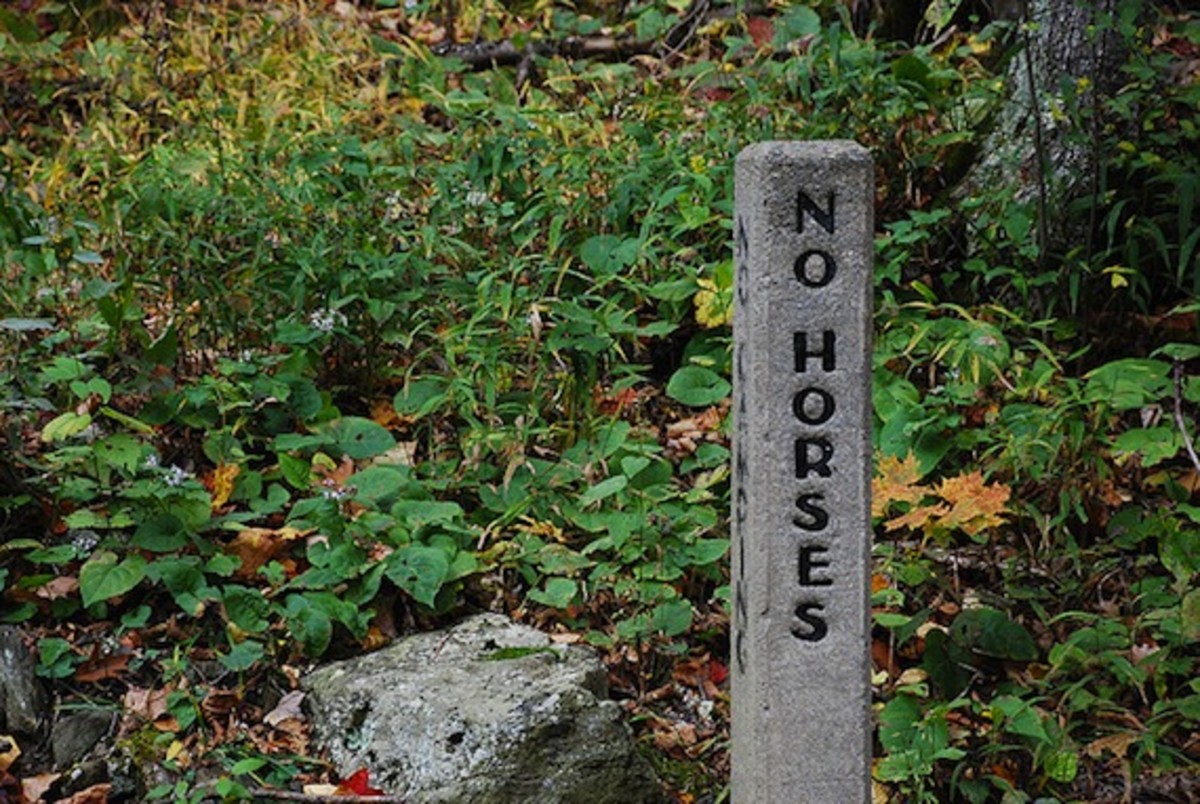

But we can see that we have some work to do, if we want to keep our horses visible on the trail. And we’d better do it before we are forced to do it, before any more “keep out” signs go up and the laws are changed.

Link to Australian paper in the journal Ecological Management and Restoration