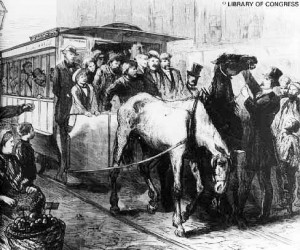

The American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals celebrates its birthday today. Did you know that the ASPCA’s roots are in one man’s desire to help the working horses of New York City? Read on to learn more; this historical insight and image (courtesy of the Library of Congress) is from the web site of the ASPCA. The image shows Henry Bergh halting a street car to examine the harness on the horses.

New York City, April 1866: The driver of a cart laden with coal is whipping his horse. Passersby on the New York City street stop to gawk not so much at the weak, emaciated equine, but at the tall man, elegant in top hat and spats, who is explaining to the driver that it is now against the law to beat one’s animal. Thus, America first encounters The Great Meddler.Henry Bergh was born in 1813, the son of a prominent shipbuilder. His adult years found him to be a man of leisure, dabbling in the arts and touring Europe. As was befitting the life of an aristocrat, in 1863 he was appointed to a diplomatic post at the Russian court of Czar Alexander II. It was there he first took action against man’s inhumanity toward animals.

Soon after, en route to America, he stopped in London to crib notes from the Earl of Harrowby, president of England’s Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, founded in 1840.

Back in New York, Bergh pleaded on behalf of “these mute servants of mankind” at a February 8, 1866, meeting at Clinton Hall. According to the next day’s edition of The Sun, Bergh impressed attendees with his indignant recollection of a family watching a bullfight in Spain who “…seemed to receive their most ecstatic throb from the maddening stab of the horned animal.”

Bergh then detailed practices in America, including cockfighting and the horrors of slaughterhouses.

A basic tenet of Bergh’s philosophy, protecting animals, was an issue that crossed party lines and class boundaries. To his audience, which included some of Manhattan’s most powerful business and government leaders, he stressed, “This is a matter purely of conscience; it has no perplexing side issues. It is a moral question in all its aspects.”

Fortified by the success of his speech and the number of dignitaries to sign his “Declaration of the Rights of Animals,” Bergh brought a charter for a proposed society to protect animals to the New York State Legislature. With his flair for drama he convinced politicians and committees of his purpose, and the charter incorporating the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals was passed on April 10, 1866.

Nine days later, an anti-cruelty law was passed, and the ASPCA granted the right to enforce it. That is exactly what the ASPCA, with a full-time staff of three, set out to do.

Bergh wrote to a reporter, “Day after day I am in slaughterhouses, or lying in wait at midnight with a squad of police near some dog pit. Lifting a fallen horse to his feet, penetrating buildings where I inspect collars and saddles for raw flesh, then lecturing in public schools to children, and again to adult societies. Thus my whole life is spent.”

The comforts Bergh gained for creatures just during his lifetime are enormous in scope. In 1867, the ASPCA operated the first ambulance anywhere for injured horses; 1875 marked the creation of a sling for horse rescue. Bergh advocated humane alternatives to live pigeons at shooting events, and supplied the horses who pulled carts and streetcars in Manhattan with fresh drinking water daily. These public fountains were visited by cats, dogs and humans, too.

By the time of Bergh’s death in 1888, the idea that animals should be protected from cruelty had touched America’s heart and conscience. Humane societies had sprung up throughout the nation?among the first to follow New York’s lead were Buffalo, Boston and San Francisco?and 37 of 38 states in the union had enacted anti-cruelty laws.

To learn more: An excellent book is Men, Beasts, and Gods: A History of Cruelty and Kindness to Animals by Gerald Carson, published in 1972 by Scribners. Bergh is described in a chapter about him as “The Don Quixote of Manhattan.” The book includes an account of Bergh stopping an act which would have required a horse to walk a tightrope across Niagara Falls. And while Bergh may have seemed the nemisis of P.T. Barnum and his circuses, the two men eventually became friends and Barnam had a monument (surrounded by horse troughs, of course) built to honor Bergh in Bridgeport, Connecticut, where Barnum lived.